Oak Downs: Dallas’ Brief Flirtation with Greyhound Racing

by Paula Bosse

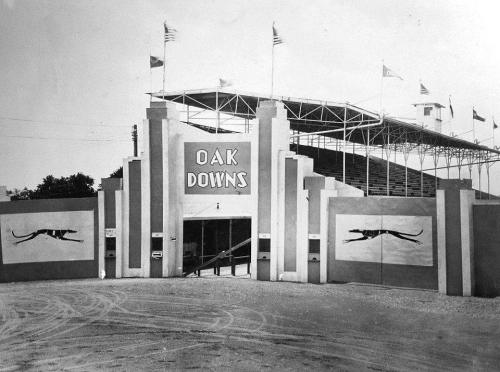

Oak Downs greyhound track, ca. 1935 (photo courtesy Robert Hurst)

Oak Downs greyhound track, ca. 1935 (photo courtesy Robert Hurst)

by Paula Bosse

Robert Hurst has shared three great photos with me: the one above, and the two below. They show Oak Downs, a greyhound racing track that he thought might have been in Oak Cliff. A dog track? In Dallas? That was news to me. Mr. Hurst came across the photos a few years ago when going through the belongings of his grandparents, Lt. Col. and Mrs. C. W. Newman. As far as he knew, they had no particular interest in dog racing, and he wasn’t sure why they would have been in possession of photos of a greyhound track. I was a little hesitant to delve into anything having to do with dog racing, but these wonderful photographs piqued my interest. (For the faint of heart, this post focuses almost exclusively on the somewhat vague and constantly changing laws on parimutuel betting in Texas, with very little on the troubling aspects of greyhound racing.)

Grandstand, daytime (click for larger image) (courtesy Robert Hurst)

Grandstand, daytime (click for larger image) (courtesy Robert Hurst)

Grandstand, nighttime (courtesy Robert Hurst)

Grandstand, nighttime (courtesy Robert Hurst)

The track was located not in Oak Cliff, but right across the street from Love Field — an area that was “north of the city” in the 1930s. It was to the west of the airfield, with the address listed, popularly, as Maple Avenue, but officially as Denton Drive (just north of Burbank Road).

1930s (Edwin J. Foscue Map Library, SMU)

1930s (Edwin J. Foscue Map Library, SMU)

*

The first mention I can find of greyhound racing in Dallas was in 1898 at events held at the Fair Park horse racing track — the “sport” then was “coursing.” I don’t want to go into it, but live hares and jackrabbits were used, and it didn’t end well for them. (Competitive coursing is, I believe, now illegal in Texas, but open-field coursing is considered hunting and is legal.)

The first professional greyhound racing track to take the “blood” out of “blood sport” by utilizing an electric rabbit lure, was in California in 1919. The first track in the Dallas area to use an electric rabbit seems to have been one that opened near Grand Prairie in 1928; the news stories made sure to mention that there would be no wagering going on because, unlike other states where dog racing had been going on for some time and was quite popular as a gambling sport, parimutuel betting was not legal in Texas. Racing at that early track doesn’t seem to have lasted very long — probably because the spectators were not allowed to wager on the contests. Another track opened just outside Fort Worth at Deer Creek in 1934 (right after Texas had legalized betting on horse races in 1933), but, again, it doesn’t seem to have lasted long.

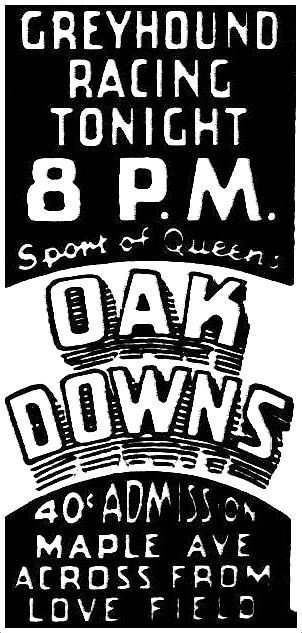

So, in the early ’30s, Texas was not really a hot-bed of dog racing enthusiasts. What was popular was horse racing — the two most popular tracks in the area were the Fair Park track in Dallas, and Arlington Downs in Arlington. The state legislature had voted in 1933 to allow parimutuel betting on horse races, hoping to raise revenue in the dark days of the Depression. People might not have been able to afford a new pair of shoes, but they managed to scrounge up money to bet with. Gambling on horse races was big business. But betting on dog races? Was it legal, too? It sounds like the law was surprisingly vague. Dog racing was not expressly written into law as being illegal — but people just seemed to understand it to be illegal. Proponents of greyhound racing — the so-called “Sport of Queens” — were adamant that they would force the state to address the issue and clarify the law — they would sue if they had to. A track in San Antonio had taken its case to a State Court of Appeals (after having been shut down by local authorities), and the court ruled that parimutuel wagering at dog tracks in Texas was not illegal. A precedent had bet set, and a few dog racing tracks began to open around the state, their owners and operators feeling they were relatively safe from prosecution.

In early 1935, 31-year old Winfield Morten, a “wealthy sportsman” who owned several businesses and a lot of Dallas real estate, decided he’d open a greyhound track on his 40 acres of land along Maple Ave./Denton Dr., just west of Love Field. He received his state business charter in May, 1935 (just days after the San Antonio ruling), and he made plans to open his dog racing “plant” — Oak Downs — in June. As they said back then, “pari-mutuel betting would be fully in vogue.”

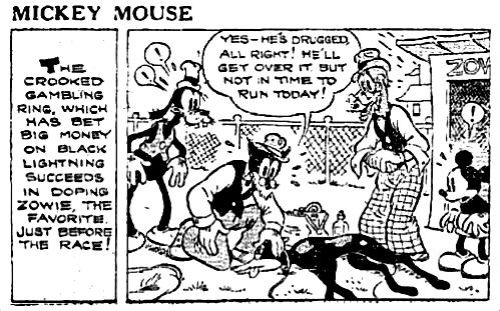

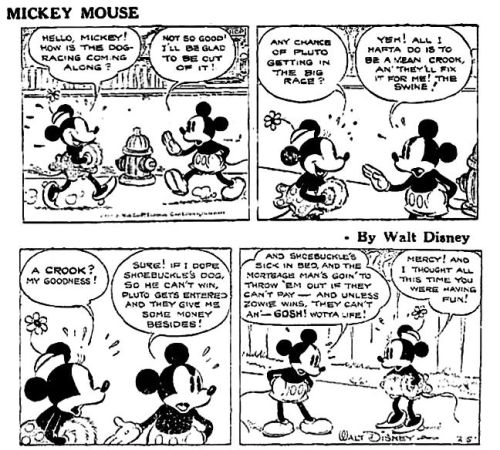

Many people did not want a dog racing track in Dallas (or anywhere in Texas, really). Owners of horse tracks (and the powerful people who were in bed with them) feared that they’d lose some of that sweet gambling moolah to the upstart “dogmen.” Outside the racing world, there was the fear/expectation that with dog tracks would come the inevitable gambling and sleazy criminal element. (Dog racing was generally seen as somehow more unsavory and déclassé than horse racing, which is odd, because the horse racing industry has never been known as a squeaky-clean one.) Also, apart from the gambling-related issues, many people were probably aware of (and disturbed by) persistent accusations of animal mistreatment. Interestingly, at this same time — during the first few months of 1935 — none other than Mickey Mouse was involved in a comic strip story arc that lasted several weeks in which he was hanging out at a dog track training his dog Pluto for a race. It wasn’t long before the comic strip (which was usually full of typical comic strip silliness and gentle humor) turned surprisingly dark, and Mickey found himself involved in a world of doping, gambling, extortion, and threatened violence (!). If Walt and Mickey were against the evils of dog racing, shouldn’t everybody be? I wonder if the strip was reflecting public opinion or shaping public opinion?

Poor Zowie! (Originally run Feb. 19, 1935)

Poor Zowie! (Originally run Feb. 19, 1935)

Mickey’s in a tough spot (click to enlarge) (Feb. 5, 1935)

Mickey’s in a tough spot (click to enlarge) (Feb. 5, 1935)

Not only was the prospect of a “seedy” dog track unpalatable for many in an image-conscious city gearing up for its upcoming Centennial-Exposition-moment in the national spotlight, but there were those who were still convinced that gambling on anything but horse races in Texas was illegal — despite what the appeals court had ruled in the San Antonio case. Several interested district attorneys from around the state petitioned the State Supreme Court for a definite ruling. In the meantime, Dallas D.A. Robert L. Hurt and Dallas County Sheriff Smoot Schmid (greatest name in law enforcement EVER) threatened to shut down the not-yet-opened Oak Downs if it allowed wagering. Battle lines were drawn, and both sides believed they were in the right.

Track manager Jack Thurman said the city’s threats didn’t scare him. He’d open as scheduled, with plans for a full season of 48 days of racing (every day but Sunday), sleek hounds, an electric rabbit, and full-tilt betting. The day before Oak Downs was scheduled to open, its operators wisely obtained an injunction against Hurt (and, basically, the Sheriff’s Department and the Texas Rangers), which prevented the track from being shut down — they would open without fear of incident, under full legal protection of a court order. Not a happy guy, Hurt said he would file a motion to dissolve the injunction … immediately!

Oak Downs opened on June 18, 1935 to a large crowd of curious spectators, most of whom had never seen a dog race. The betting windows were open, but there was little betting. There were problems with the electricity in the stadium on opening day — the electric-powered rabbit that the greyhounds chased was not running on full power, and it moved so slowly that it was caught in two separate races by the probably confused dogs. (The second night there was too much juice, and the rabbit shot away from the pack so quickly that the dogs lost sight of it and just stopped running altogether. Hard to have a race if the dogs don’t actually run.) But the crowd seemed happy, and they weren’t overly concerned by the glitches happening there at the track or by the political and legal wranglings that were swirling downtown.

The crowds and the betting increased over the next few days, hinting at a rosy future for the track’s operators. But the races and the attendant wagering continued for only eleven days. The United States Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals refused to interfere with the wishes of State law enforcement — and State law enforcement wanted Oak Downs to cease with the gambling. So there was no more parimutuel betting at Oak Downs. After trying to struggle by without the sexy allure of betting — left with nothing but exhibition races and weird novelty events involving dog-riding monkeys — Oak Downs was forced to close its season prematurely on June 29.

Bye-bye, abbreviated inaugural season. No more betting on Doctor Snow, or Dixie Lad, or Rowdy Gloom, or Miss Cutlet, or Pampa Flash, or Billie Hobo, or Blond Hazard, or Mellow Man. Oh, Mellow Man, we hardly knew ye.

In February, 1936, Morten applied to the Texas Racing Commission for permission to race horses at his track, but the idea was quickly shot down by the Dallas City Council. The very profitable horse track at Fair Park was out of commission for 1936 as it was being used as part of the Centennial Exposition. Privately owned at the time, the track was leased to the Centennial Corporation, and the City Council — the members of which were no doubt on very friendly terms with the Fair Park track owner — felt it would be “unfair” to allow a competitor to horn in on the massive profits to be had. So … no dice (…as it were).

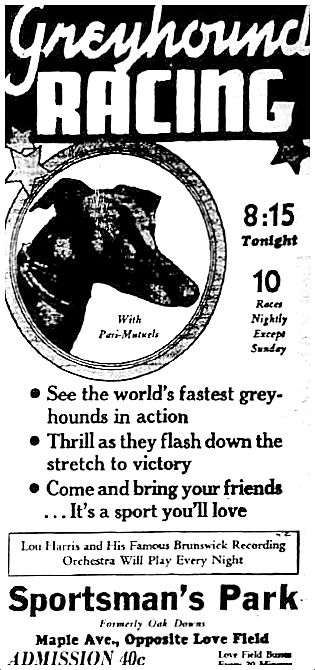

By September of 1936, Morten changed Oak Downs’ name to Sportsman’s Park and brought in new operators (including a former Texas Ranger). Oak Downs had joined other dog tracks in a new round of legal action which was slowly working its way through the courts. Without any ruling yet from the Supreme Court, they ignored an injunction that had been filed against them and defiantly opened up their betting windows again. Four of the men were fined and jailed briefly for contempt of court. But after months of mixed messages and conflicting rulings from various judges around the state, confused and fed-up lawmen were unsure of the actual legality of dog track betting, and, grudgingly, they allowed the wagering at Oak Downs to continue as they, too, awaited a high court decision.

As reported in Texas newspapers, on Oct. 28, 1936 the Texas Supreme Court finally ruled on the matter of whether or not dog racing could be wagered on legally in the state of Texas:

We do not find any provision in the penal code defining gaming which can be construed to include dog racing or betting on dog racing. It is not a game prohibited by law. […] This court is fully conscious of the pernicious and unwholesome effects upon society of betting on dog races and keeping premises for dog racing where betting is allowed, but the proper agency for the suppression of those wrongs is the Legislature, and until it sees proper to further legislate in the matter, the courts are without power to suppress these evils by injunction.

In other words, the Texas House and Senate were going to have to take up the issue if they really wanted to do away with legalized betting on dog races (which they did), because it was their fault that they hadn’t been specific enough when they wrote their original law.

So betting was back “in vogue” once again. And now with absolutely no threat of arrest. The remainder of the 1936 season continued without problems, and when the 1937 season opened in April, it was “the first greyhound meet in Dallas free of danger of being interfered with by law enforcement agencies” (DMN, April 22, 1937), but … as there were bills to outlaw betting on dog racing AND horse racing percolating through the current Texas legislature, it was thought that the 1937 season might also be the last season of racing in Texas.

In May, 1937, Governor James V. Allred addressed the Texas Congress, urging them to repeal the current law allowing parimutuel gambling on horse racing (with the knowledge that this would almost certainly also apply to the outlawing of dog racing, as that bill had just passed the House and was headed to the Senate). Here are a couple of passages from his speech, a transcription of which appeared in newspapers throughout the state on May 28, 1937:

I do not know how to state in words a stronger case for repeal of the race track gambling law than I have already given to this Legislature from time to time. I have quoted Washington, Franklin, Blackstone, Shakespeare, Brisbane, McIntyre and the Holy Bible. I have pointed out the living evidence of undesirables, of doping, of thuggery, of embezzlement, of bank failures, of suicides, and narcotic rings. Each month of the life of this law sees addition to the numbers of these human tragedies….

And, finally, a mention of the evils of racing with regard to the animals themselves:

There is no record of a horse ever being doped except to run a race. All the races ever run are not worth the agony and cruelty dealt even one of these poor, helpless beasts! I appeal to all who love good horses, I appeal to all who believe in preventing cruelty to animals to join with me in demanding that this law be repealed.

Allred’s lengthy and impassioned speech — which addressed every argument the pro-gambling forces were wont to … trot out … must have touched a few nerves (with both the public and the politicians), because in June, both bills passed with huge margins. (The bill outlawing the betting on dog racing passed in the Senate 22-1 and in the House 109-12. With passage of the new law, betting on dog races could now incur a fine of up to $500 and a jail term of up to ninety days; the penalty of “keeping a place of betting on dogs” was two to four years in the state penitentiary.)

So no more parimutuel betting in Texas. No more dog racing. No more horse racing.

And that was that for the state’s dog tracks. What was next for Oak Downs … er, Sportsman’s Park? Three words: “midget auto racing” (i.e. the racing of very small cars, not the racing of cars operated by very small drivers).

Besides the regular auto races, two added events give promise of furnishing fans with a few thrills as well as a laugh or two. Fast cowponies will be featured in a half-mile sprint with a race for roosters rounding out the show. Winner of the cowpony race will receive $15, while the winning rooster will be rewarded with $5. Entries are open to any and all owners of ponies or roosters. (Dallas Morning News, Aug. 27, 1937)

Somehow I don’t think five-buck-purse rooster races figured into Mr. Morten’s big dreams back at the beginning of 1935.

1935

1935

*

1937

1937

***

Sources & Notes

Top three photos of Oak Downs greyhound racing track used by kind permission of Robert Hurst. He came across them several years ago in the belongings of his grandparents, Lt. Col. Campbell Wallace (C. W. “Bub”) Newman and Martha Price Newman. Col. Newman was a cavalry officer who served in WWI, WWII, and Korea; between WWI and WWII, he worked in Dallas as a contractor and was employed for a time at Oak Downs where he worked in track operations. (That’s why he had these photos!) [And by no means do I mean to imply that this career military man was involved in any sort of shady goings-on. In fact, from what I can tell, Oak Downs seems to have been run by a fairly “clean” group of people. The perception/reputation of dog racing at the time wasn’t great, but nothing I’ve read about this track suggests that anything unscrupulous was going at the track, behind the scenes, or amongst the personnel who worked there.] He was also an avid polo player and was a good friend (and polo teammate) of Winfield Morten who owned the track. Many thanks, Mr. Hurst, for the use of these wonderful photos!

Black and white aerial view of the Love Field/Bachman Lake area was taken by Lloyd M. Long in the 1930s; photo is from the Edwin J. Foscue Map Library, Southern Methodist University. The unlabeled photo (a detail of which is used above) can be accessed here; a labeled version of this photo (with some streets and buildings identified) can be accessed here.

I highly encourage people to see out the transcript of Governor James V. Allred’s FANTASTIC impassioned speech before members of the Texas House and Senate, which appeared in newspapers around Texas on or around May 28, 1937. As far as politics is concerned, I’m the most cynical person in the world, but this is an incredible speech.

More on the history of parimutuel gambling in Texas from Wikipedia, here.

An explanation of just what parimutuel betting is, is here.

Parimutuel racing was legalized again in Texas in 1987. The current state of racing in Texas can be read about in the Dallas Morning News article “A Last Hurrah for Texas Horse Racing” (May 3, 2014) by Gary Jacobson, here.

I’m quite honestly shocked to learn that greyhound racing is legal in the state of Texas. There seems to be really only one active track with live racing in the state (in South Texas), and the only upside to this appalling fact is that attendance has been in steep decline for years.

*

Copyright © 2015 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

wonder what the two tracks east of Love Field were used for?

LikeLike

There was auto racing in the area at the same time, but I think the oval(s) to the east of Love Field belonged to the Dallas Polo Club. The club was built around 1931 and was located at Lemmon and Lovers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for a glimpse into my family’s history that I was never aware of until now! For the record: my grandparents were very much law-abiding citizens. 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you, Mr. Hurst! I would never have known about this if you hadn’t shared the great photos! It seems that just about everyone connected with this particular track was fairly upstanding. (I found out that your grandfather also worked on the remodel of the Arcadia Theater — I’ll send a little packet of interesting family tidbits a little later!)

LikeLike

[…] doing research for my recent post on the Oak Downs/Sportsman’s Park greyhound racing track across from Love Field, I came across, of all things, a 1935 Mickey Mouse comic strip story arc about dog racing. The […]

LikeLike

[…] “OAK DOWNS: DALLAS’ BRIEF FLIRTATION WITH GREYHOUND RACING.” I never would have guessed that Dallas had a dog racing track, but then a reader sent me an amazing […]

LikeLike

[…] Thanks to the great photographs shared with me by reader Robert Hurst, I learned about a long-forgotten bit of Dallas’ sporting history: the very, very brief time when greyhound racing was a thing in Big D. I wasn’t sure I’d enjoy looking into this, but it was incredibly interesting. And I sort of understood parimutuel betting for a tiny sliver of time. I really loved writing this! Check out the Flashback Dallas post from 2015, “Oak Downs: Dallas’ Brief Flirtation with Greyhound Racing.” […]

LikeLike