F. J. Hengy: Junk Merchant, Litigant

by Paula Bosse

by Paula Bosse

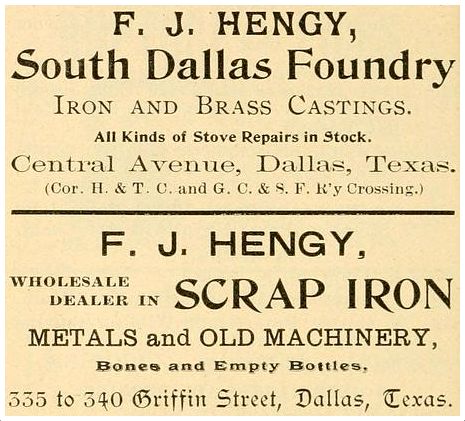

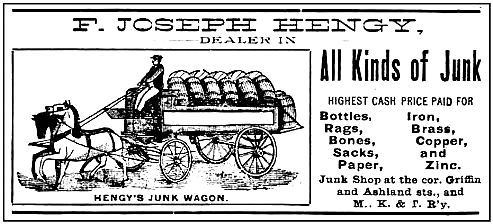

Frank Joseph Hengy was born in Germany in 1850. He immigrated to the United States in 1873, and in about 1880 he made his way to Dallas with a wife and children and established himself as a prosperous buyer and seller of scrap metal and other assorted “junk.” He also owned and operated a foundry, producing amongst other things, sash weights. In the 1894 city directory, there were exactly two “junk dealers” listed, which is surprising, seeing as Dallas was a sizable place in 1894 — there must have been a lot of bottles, rags, bones, sacks, paper, iron, brass, copper, and zinc lying around all over the place, just waiting to be hauled away.

Souvenir Guide to Dallas, 1894

Souvenir Guide to Dallas, 1894

F. J. “Joe” Hengy’s junkyard (and adjacent residence) was at Griffin and Ashland, right next to the M K T Railway tracks. He advertised in the newspapers constantly and was apparently THE man to sell your junk to. His name even made its way into the minutes of an 1899 city council meeting, when, during the discussion on how the city was going to pay for the shipping of a Spanish cannon that had been captured in Cuba and had been given to the city as a war trophy, a councilman asked sarcastically, “What will Hengy give for it?” (Dallas Morning News, Aug. 5, 1899).

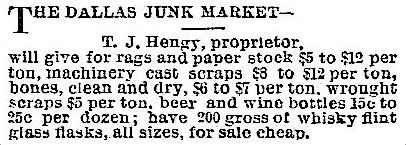

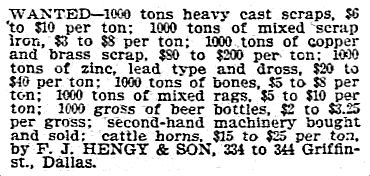

But, seriously, got junk? Call Hengy. Got tons of it? By god, he wants it. A couple of examples of the endless ads placed over the years — two ads, 12 years apart (the 1887 one getting his first initial wrong).

DMN, Aug. 24, 1887

DMN, Aug. 24, 1887

DMN, Oct. 22, 1899

DMN, Oct. 22, 1899

In the mid-1890s, Joe took his son Louis on as a partner, which, in retrospect, was probably not a good idea, because it wasn’t long before Joe found himself in the middle of years and years of lawsuits: father against son, son against father, father and associates against son, son and associates against father, etc. Not only was he constantly being sued by his son, he was also sued for divorce … twice … by the same woman. He turned around and sued her for custody of their youngest children (and won). She sued him for the business when he was threatening to sell it and retire. He sued her back for something or other. And on and on and on.

Not only was Joe spending all his non-junk-hauling time traipsing about courthouses, but he also found the time to suffer the occasional partial destruction of buildings on his property — twice by fire and once by the massive flood of 1908. The fires were suspicious (the flood was not).

Then there was the time he was charged with the crime of mailing an obscene letter (I’m gonna go out on a limb and guess that it was probably a letter sent to his wife — or maybe ex-wife by that point — who was in the midst of suing him and their son). Even though this was a potentially serious federal offense, he was ordered to pay only a small fine for “misuse of the mails.” He was also charged at one point with “receiving and concealing stolen property,” but I’m not sure that got past a grand jury investigation, and one might wonder if there wasn’t some sort of “set-up” by aggrieved relatives involved. It was something new anyway. Probably broke up the monotony a little bit.

But the thing that seems to have been Hengy’s biggest headache and was probably the root of most of the lawsuits filed BY him and AGAINST him concerned property he owned which had been condemned in the name of eminent domain by the M K T Railway. The condemnation was disputed, the appraisal of land value was disputed, the question of which Hengy actually owned the land was disputed, etc.

By the end of 1913, Joe Hengy had been engaged in at least 10 years of wall-to-wall litigation. He moved to Idaho at some point, remarried, started another business, and, finally, died there in 1930. Let’s hope his later years were lawsuit-free.

*

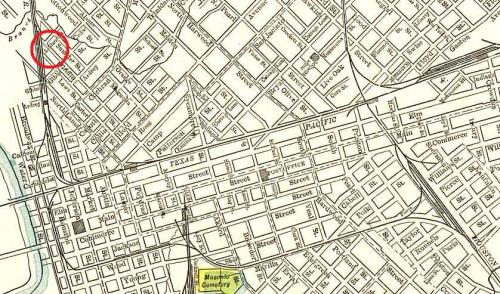

Hengy’s business and residence (which was, surprisingly, right next door to his litigious son) was at 2317 Griffin, very close to the present-day site of the Perot Museum. (Full map circa 1900, here.) (Click for larger image.)

*

Lastly, two odd, interesting tidbits.

Joe Hengy took time out from junk and courtrooms to invent new and improved … suspenders! I’m not sure exactly what was so revolutionary about them, but a patent was granted in 1912 — you can read the abstract here, and see them in all their suspendery glory here. (With so much foundry and scrap metal know-how, you’d think he’d go in a more … I don’t know … anvil direction or something.)

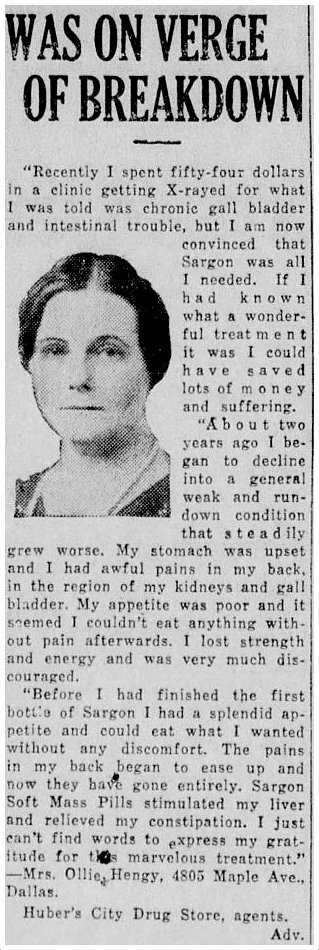

And, then there’s this — a kind of sad ad for a tonic called “Sargon” with a testimonial from Mrs. Ollie Hengy, the no doubt long-suffering wife of perennial plaintiff/defendant Louis Hengy. “Was On Verge of Breakdown.” I don’t doubt it! (Incidentally, Ollie and Louis divorced the same year this advertisement appeared in Texas newspapers. Maybe that stuff did work.)

1929

1929

***

Sources & Notes

Top ad from Dallas’ 1890 city directory.

Sargon ad appeared in The Vernon Daily Record, Sept. 6, 1929. More on the quack tonic Sargon here.

Sources for other clippings and images as noted.

Lastly, an interesting article that answers the questions “Why was the scrap metal game profitable?” and “Just where did all that metal GO, anyway?” can be found in the article “Many Uses for Junk: How Wornout and Discarded Metal is Utilized,” originally published in The Brooklyn Citizen in 1899; it can be read here. I’m nothing if not exhaustive.

*

Copyright © 2015 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

Absolutely delightful reading all of this. I remember seeing a junk man in our neighborhood in Wichita Falls in the 30s when I was growing up. Had an old mule and cart. The cart really stunk, but my grandmother saved scraps of metal cans, some greasy rags and other bits and pieces for him. But when WWII came we saved grease, cans which we stomped flat, anything made of rubber and those were picked up by the army truck. Old clothes and such were given to First Methodist Church for their yard sale once a year.

LikeLike

Thank you, Jeanette. Early recycling.

LikeLike

Stories like this form the warp and woof of civilization, and your tonier historical accounts won’t touch ’em with a ten foot pole. I would rank Mr. Hengy and his life’s work rank right up there with the Meisterhans beer garden of beloved memory. Thank you.

LikeLike

Thank you, Bob! You know what they say: one’s man’s junk….

LikeLike

He was the junk man that Jim Wheat and myself had worked on for a number of years in research, and he had lived in the Little Mexico over by Wolf Street area and his sons Shop is still in Fair Park under the Hengy Electrical company on Exposition….AND i had dug in this are in 2000 when the Dallas arena area was made with the E.P.A standards that removed the dirt from his area, we had too locate since hew as also in the silver recycling business along with bottles and newspapers and he ran a Hobo camp on one side since these were his scavengers who would work for him in gathering up trash….for recycle….he is buried in Calvary cemetery and was a devote catholic…

LikeLike

Frank Joseph Hengy was my great grandfather so I find this history especially fascinating.

LikeLike

Thanks! I really enjoyed researching him!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Frank Joseph Hengy was my great great grandfather. Louis Hengy was my great grandfather. Wonder how we are related?

LikeLike

[…] “F. J. HENGY: JUNK MERCHANT, LITIGANT.” There’s money in junk. Enough to keep an attorney on permanent […]

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] Who was the top man in junk in turn-of-the-century Dallas? It was F. J. Hengy, who, when not practicing his junk business, seems to have spent all of his free time in court suing and being sued. Read about this interesting early Dallasite in the Flashback Dallas post from 2015, “F. J. Hengy: Junk Merchant, Litigant.” […]

LikeLike

[…] Co.” — back in 2015 I wrote a long post about the exceedingly litigious Hengy family (“F. J. Hengy: Junk Merchant, Litigant”) (J. M. was the grandson of F. J.). The Hengy Electric Co. was in business at that location from at […]

LikeLike