2222 Ross Avenue: From Packard Dealership to “War School” to Landmark Skyscraper

by Paula Bosse

Packard automobile showplace, 1940 (click for larger image)

Packard automobile showplace, 1940 (click for larger image)

by Paula Bosse

In late summer of 1939, a new 60,000-square-foot. $250,000 home for Packard-Dallas, Inc. featuring a “luxurious showroom” was announced. The first Packard automobile dealership had opened in 1933 at Pacific and Olive, and in the intervening six years, their growth had been tremendous, necessitating several moves and expansions.

The attractive art deco building, faced with Cordova limestone and decorated with glass bricks, cast aluminum letters, and neon, was designed by J. A. Pitzinger and Roy E. Lane Associates, and was constructed at 2222 Ross Avenue in a mere three months. The large building was right across the street from the Cathedral of the Sacred Heart, in the block bounded by Ross, Crockett, San Jacinto, and N. Pearl. The president of Packard-Dallas was J. A. Eisele and the secretary-treasurer was his son, Horace. The grand opening on Dec. 16, 1939 was a big enough deal that the home-office Detroit honchos flew in, and there was even a 15-minute radio program devoted to it on KRLD.

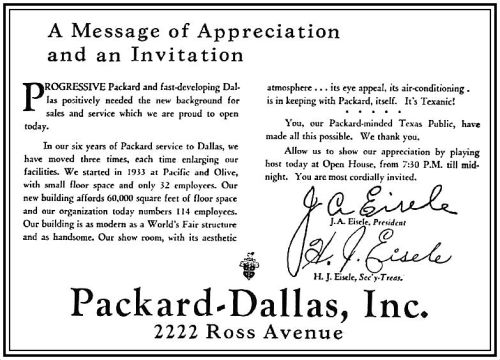

Under the headline “Growing With Dallas,” the opening-day ad featured a photograph of Joe and Horace Eisele and “A Message of Appreciation and an Invitation”:

Ad, Dec. 16, 1939 (click for larger image)

Ad, Dec. 16, 1939 (click for larger image)

“It’s Texanic!”

And another ad featured this nifty little line drawing of the cool building:

One of the stories about the opening of Dallas’ new auto showroom palace boasted that this big, beautiful, brash building was here to stay — Packard-Dallas had a 15-year lease on the place. …Which is why it was surprising to read that the building was sold less than two years later.

The U.S. was on the inevitable brink of involvement in the European war, and the National Defense School had begun operation in Dallas in July, 1940. After a year of classes in which young men were taught “to do the technical and mechanical work necessary to warfare” (DMN, March 20, 1941), classrooms at the Technical high school and at Fair Park were bursting at the seams, and a larger facility was necessary. The Dallas Board of Education (which oversaw the program, often called “the War School”), was given the go-ahead to purchase the building (and, presumably, the property) for $125,000 in August, 1941.

I’m not sure why J. A. Eisele sold the building (his name was listed as owner, rather than the Packard Company) — it wasn’t even two years old, and he got only half of what it cost to build. Patriotism? His son Horace had been drafted in April, so … maybe. Eisele seems to have left the auto sales business, which he had been in for decades, and had moved out of Texas by 1945.

After the U.S. officially entered the war and it became obvious that “defense schools” around the country would have to admit women in order to maintain manufacturing quotas, women began to work beside men at the Ross Avenue school in January, 1942.

Eighty women Saturday pulled their fingers against the triggers of aircraft rivet guns as the Dallas National Defense School, 2222 Ross Avenue, started the state’s first major training course designed to place women side by side with men in Texas war materials plants. (DMN, Jan. 4 1942)

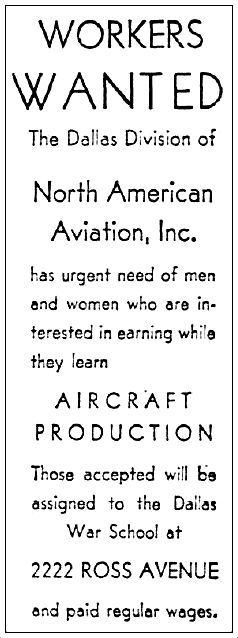

This “War School” was a training school for war-time jobs at places like North American Aviation.

Sept., 1943

Sept., 1943

Thousands of men and women trained at the Ross Avenue facility until the war ended in 1945. The school continued, but no longer as a Defense School — it became Dallas Vocational School, and its first students were veterans.

In 1976, the school was designated as one of the Dallas Independent School District’s magnet schools — it became the Transportation Institute, where “students interested in owning their own dealership, becoming a technician-mechanic or an auto body specialist will receive on the spot training in a laboratory consisting of a new car showroom, a modernly equipped repair center and a complete auto rebuilding facility” (DMN, Aug. 22, 1976). Back to its roots! And it only took 37 years.

The school continued for a while but, inevitably, the property became more and more attractive to developers. In 1981, as the developers were circling, a City Landmark Designation Eligibility List was issued. It contained buildings which had “particular architectural, historical, cultural and/or other significance to the City of Dallas,” and, if approved, were eligible to receive historic landmark designation. I’m guessing 2222 Ross Avenue didn’t make the cut, because Trammell Crow bought the building in 1983 and tore it down the next year.

But … Crow sold the facade to real estate developer and investor Lou Reese, who said that he would reassemble the limestone facade and incorporate it into a restaurant he planned to build in Deep Ellum. That was an interesting plan. (Incidentally, in the same city council meeting in which the demolition/disassembling of the building’s facade was discussed, the council also considered “a request for more than $7 million in federal funds for a project to renovate the Adams Hat Co building into apartments” (DMN, Aug. 8, 1984). …Lou Reese owned the Adams Hat building. What a coincidence!)

The city council’s decision?

The council authorized developer Trammell Crow to disassemble the art deco facade of the former Transportation Institute Magnet High School on the condition that the facade be reconstructed in Deep Ellum…. The company [has] demolished all but the building’s limestone facade, which was determined to be eligible for designation as an historic landmark. (DMN, Aug. 9, 1984)

So? Where’s that facade? There was no mention of it for three years, until an article in the Morning News about another developer who had big plans for a major Deep Ellum complex called “Near Ellum,” which would be be bounded by Commerce, Crowdus, Taylor, and Henry streets.

Highlighting Near Ellum will be a 40-foot art deco facade, formerly on the front of the Transportation Institute on Ross Avenue, in the main parking plaza. The plaza will also include an outdoor stage for concerts and special events. (“Developer Plans Deep Ellum Project,” DMN, June 25, 1987)

Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaand … that never happened. I wonder if that 76-year-old disassembled limestone facade is still crated up somewhere around town? Somehow I doubt it.

So, 2222 Ross Avenue. What’s there now? None other than the 55-story skyscraper, Chase Tower, also known as “The Keyhole Building.”

You could get a lotta Packards in there.

***

Sources & Notes

Top photo from the Detroit Public Library’s Packard Collection in the National Automotive History Collection, viewable here; I’ve straightened and cropped it. The reverse has this notation: “Packard Motor Car Co., branches/dealerships/agencies, 2300 [sic] Ross Avenue Dallas, Texas, exterior, show windows left to right; 1940 Packard 110 or 120, eighteenth series, model 1800 or 1801, 6/8-cylinder, 100-120-horsepower, 122/127-inch wheelbase, convertible coupe (body type #1389/1399), special furniture display.”

The developer who apparently came into possession of the facade after Lou Reese was Ed Sherrill. Perhaps someone associated with the Near Ellum project might know what became of the “saved” facade.

Chase Tower info on Wikipedia here; photo of it here. Imagine a teeny-tiny car dealership at its base.

Packard automobiles? Some of them were pretty cool. Check ’em out here.

A lengthy article on the notorious developer Lou Reese — “Hide and Seek” by Thomas Korosec (Dallas Observer, June 8, 2000) — is here.

Most images larger when clicked.

*

Copyright © 2015 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

Nice! Do you have anything on the old Tucker dealership on Ross? It’s now three sheets bar and they kept the original flooring!

LikeLike

I had no idea Dallas even HAD a Tucker dealership!

LikeLike

It looks like the developer who bought the facade, Louis Reese, passed away in 2008 (http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9C02E2DC173AF93AA35754C0A96E9C8B63). It also looks like he might have been in some bit of hot water at one point as well (http://www.dallasobserver.com/2000-06-08/news/hide-and-seek/).

I’d be very interested if the facade is somewhere in storage. It would be such a magnificent piece to front a patio cafe or something like that. Thanks for finding this one, Paula!

LikeLike

Wait, I’m dumb. Scratch that, looks like Reese sold the properly.

LikeLike

And the man who bought it, C. Edgar Sherrill, has also passed away (2012 http://www.cpcleburne.com/services.asp?page=odetail&id=118&locid=#.VR8JmZPF8gk)

LikeLike

that intersection dates back too the 1870s John Henry Brown lived there in A.C.Green old photo book…..and a map of the area is listiing that section, it is the high end of the 1870s.

LikeLike

Thanks, Justin. Yeah, it looks like it will probably remain a mystery….

LikeLike

he is correct it went into storage, but it is gone now….

LikeLike

Hi altroup, any idea where it might have gone to? I’m very curious about this one if you have any other information.

LikeLike

It was changed from a retail dealership, possibly due to the stoppage of automobile production due to World War II.

LikeLike

[…] “2222 ROSS AVENUE: FROM PACKARD DEALERSHIP TO ‘WAR SCHOOL’ TO LANDMARK SKYSCRAPER.… I still wonder what happened to that art deco facade that was carefully removed and packed away to […]

LikeLike

[…] Another Flashback Dallas post on a local munitions plant (this one downtown) — “2222 Ross Avenue: From Packard Dealership to ‘War School’ to Landmark Skyscraper” — is here. […]

LikeLike

this is the first time I’ve really read this article and a name jumped out at me, Lou Reese. Isn’t this the same Lou Reese who was a real estate developer in deep ellum in the 80’s and ended up going to prison for the S&L crisis/scandal that claimed a number of Dallas real estate/banking tycoons. (that’s right Tommy and Jack Gaubert, I’m talking to you)

LikeLike