“Enemy Aliens” and the WWII Internment Camp at Seagoville

by Paula Bosse

Dallasites rounded up the day after Pearl Harbor… (click for larger image)

Dallasites rounded up the day after Pearl Harbor… (click for larger image)

by Paula Bosse

I think most of us know about the sad period in American history of Japanese internment camps when, following Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor, the United States “interned” men, women, and children of Japanese descent (often including whole families, some of whom were born in America or were naturalized American citizens). I’ve always thought of these camps as being in the western part of the country. I had no idea until just a couple of days ago that there were three “enemy alien” internment camps in Texas — and one of them was in Dallas County.

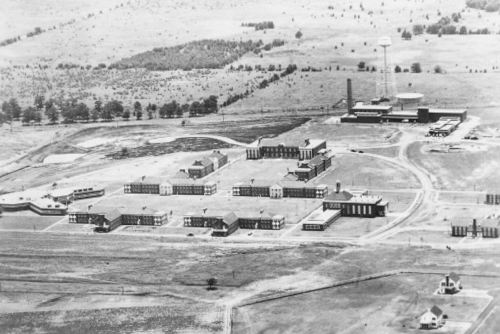

For a full history of the camp in Seagoville — which is a mere 20 miles southeast of Dallas — there are several links at the bottom of this post. But, briefly, the “camp” was originally built as a federal women’s prison in 1938 on 800 acres of farmland. The United States entered World War II as a result of Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, and, suddenly, authorities began scrambling to round up enemy aliens living in the U.S.: people born in countries we were now at war with — primarily those of Japanese, German, and Italian descent — were rounded up and questioned. Many were arrested, and some were interned in camps where they were basically kept prisoner for the duration of the war. Even though the bulk of the initial internees were, oddly enough, from Latin America (most of them Japanese, most sent from Peru), there were also several who, before the war, had been living in the United States for decades without any problems. (See a dizzying number of links at the bottom of this post for more on the Texas internment camps at Seagoville, Kenedy, and Crystal City.)

Below, the Seagoville camp.

In December, 1941, authorities in every city in the country were swooping down on foreign nationals (or sometimes just people who looked foreign or spoke with an accent), hauling them in for questioning, often arresting them for nothing more than the fact that they had been born in another country. Dallas was certainly no exception. Unsurprisingly, immediately following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Dallas’ few Japanese residents were rounded up. All ten of them. The photo at the top shows five of the first detainees, at the Dallas jail.

Most of Dallas’ Japanese residents worked for the Japan Cotton Company, an important cotton broker which had occupied space in the Dallas Cotton Exchange building since the late 1920s. (For a bit of weird trivia, the father of famed gossip columnist Liz Smith was working as a cotton buyer for the company during the war, commuting to work from Fort Worth.) If they weren’t working for the Japan Cotton Company, they were probably members of two Japanese families with long ties to Dallas: the Muta and Sekiya families, owners of the respected Oriental Art Company since 1900.

In February, 1942, the Associated Press photo below appeared in several newspapers, along with the following caption: “This is a portion of the contraband radios, cameras, guns, that were seized during all-night raids on residences of enemy aliens in Dallas County, Texas, by federal and local officers. Scores of aliens also were taken into custody.”

Lubbock Avalanche, Feb. 26, 1942 (click to read)

The first internees arrived in the Dallas area in April, 1942. The group was comprised of 250 women and children (“citizens of the Axis nations”) who had been arrested in Panama. They were interned in Seagoville, displacing the federal women prisoners who had previously been held there — they were transferred to a prison in West Virginia.

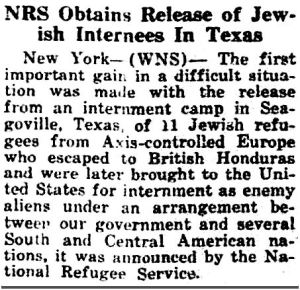

Jewish refugees sometimes found themselves tossed into enemy alien internment camps — simply because they had fled homelands which happened to be “Axis-controlled” countries with which the U.S. was at war (even though is seems highly unlikely that a German Jew would be an ardent Nazi sympathizer, gathering classified information to send the Führer’s way). Yes, Seagoville had detainees from all over the place. It was quite the melting pot. There was even a Bavarian princess in there. I wonder if a single person in that camp, held against his or her will for months and years, posed any actual threat to Allied forces.

Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, May 28, 1943

Germans and Italians were able to “blend in” to American society, but Asian men and women had a harder time and were more often harassed. The person who seems to have most disliked and distrusted Japanese people was top Dallas police detective Will Fritz — in fact, The Dallas Morning News called Fritz “one of Dallas’ most enthusiastic Jap-haters” (DMN, Feb. 17, 1943). Let’s just say that Capt. Fritz wasn’t going to be sending the wartime Welcome Wagon to any prospective Dallas residents of Japanese descent.

One Dallasite who was pretty angry and unhappy with the situation was Masao Yamamoto, an executive with the Japan Cotton Company who had lived in Dallas since 1928. He and his wife and two young sons (one of whom was born in Dallas) were living what appears to have been a nice life in the M-Streets when they were “detained.” Ultimately, the Yamamoto family was deported and sent to Tokyo, six months after the photo at the top of this post was taken (Mr. Yamamoto is the third from the left in the top photo) — they were part of a sort of prisoner swap.

After his deportation, Mr. Yamamoto complained to the Japanese press about his treatment in Dallas, where he said he was arrested, relieved of his possession, and thrown in jail with “burglars, murderers, deserters and other criminals.” (Click to see larger image.)

Will Fritz just about had a seizure when he heard of Yamamoto’s complaints, insisting that he was not mistreated and that he was a dangerous enemy agent: “Any apology that may be due should go to the murderers and burglars instead of Yamamoto. […] He was deported for we have absolute proof he was an agent of the Imperial Japanese Government and that his cotton-buying story was just another Jap blind. I consider him one of the most dangerous of enemy agents” (DMN, Feb. 17, 1943). (This is from the article which described Fritz as “one of Dallas’ most enthusiastic Jap-haters.”)

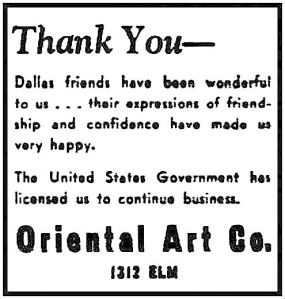

But even in the midst of all this paranoid nastiness, there were occasional heartwarming moments. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Oriental Art Company — the 40-year-old business owned by Hideo Muta (who came to Dallas in 1900) — was ordered closed. In a show of support, 200 of his friends, neighbors, and customers signed a petition vouching for his staunch American patriotism (which is plainly evident in his 1951 obituary in which he is described as a “patriot”). In the ad below, the 73-year-old Muta acknowledged the support of his Dallas friends and announced the reopening of his business in an ad taken out on Dec. 15, 1941: “Thank You — Dallas friends have been wonderful to us … their expressions of friendship and confidence have made us very happy. The United States Government has licensed us to continue business. Oriental Art Co., 1312 Elm.”

Mr. Muta was spared the “enemy alien” internment camp, but, along with other Asian men and women residing in the United States, he was barred from becoming a naturalized U.S. citizen because of the “Oriental Exclusion Act.” The inability of Mr. Muta to become a U.S. citizen did not dampen his enthusiasm for American democracy: he paid his poll tax every year, even though he was not allowed to vote, and he was a proud member of the Dallas Chamber of Commerce for over 25 years.

The Seagoville Enemy Alien Detention Station was closed in May, 1945, and the site was returned to the Bureau of Prisons.

***

Sources & Notes

Photos of the Seagoville camp are from the Institute of Texan Cultures (UTSA).

Articles of interest from The Dallas Morning News:

- “Six Japanese Taken in Custody By Local Police” (DMN, Dec. 8, 1941)

- “Dallas Japs Questioned” (DMN, Dec. 9, 1941)

- “Six Suspected Germans Held in Dallas Roundup of Aliens; Total of Jap Prisoners Rises to 10” (DMN, Dec. 9, 1941)

- “Enemy Aliens In Dallas, 776; Arrested, 30: But All Suspects Are Closely Watched By G-Men and Police” (DMN, Dec. 19, 1941)

- “FBI Rounds Up 50 Enemy Aliens, Seizes Arms, Cameras, Radios” (with photos of Dallas residents of Japanese, German, and Italian descent as well as seized “contraband”) (DMN, Feb. 25, 1942)

- “Women Aliens Are Interned At Seagoville; 250, Including Their Children, Arrive Here From Panama” (DMN, April 11, 1942)

- “Chilly Welcome Given 15 Japs From Coast; O.K. to Come to Dallas, Were Told; Still More On Way, Inform Police (DMN, April 23, 1942)

- “Japs Leave Dallas” and “Tokyo-Bound Jap Lad Takes Candy Six-Gun as Souvenir” (about the deportation of the Yamamoto family, with photo) (DMN, June 6, 1942)

- “Fritz Sheds No Tears For Mr. Yamamoto” (DMN, Feb. 17, 1943)

- “Japanese Woman Revisits Seagoville” by Roy Hamric (profile of Masayo Ogawa) (DMN, Sept. 8, 1970)

- “American Gulag: When Seagoville Housed the Aliens” by Kent Biffle (DMN, July 23, 1978)

More articles on the Seagoville internment camp:

- One of the best articles I’ve read on the camp was an interview with two men (Erich Schneider and Alfred Plaschke) who, as American-born children of German parents, were interned at Seagoville and were later deported to Nazi Germany (in a prisoner exchange) where they experienced the terrifying bombing of Dresden. Both families returned to the United States after the war. The article by Mark Smith — “German-Americans Recall Horror of Deportation — Hundreds of Detainees Sent to Nazi Germany in POW Trade” — appeared in the Houston Chronicle on Nov. 11, 1990, and can be read here.

- “Seagoville Enemy Alien Detention Station” (Texas Historical Commission), here

- “World War II Internment Camps” (Handbook of Texas), here

- “Seagoville, South America, and War — A Historic Intersection” by Kathy Lovas (Legacies, Fall, 2000), here

- “Seagoville Detention Facility” (Densho Encyclopedia), here (and for more on the Japanese-American experience overall, see the main page, here)

- “The Japanese Texans” by John L. Davis (Institute of Texan Cultures), here (opens a PDF)

Thanks to friend Julia Barton for posting about (and suddenly making me aware of) the Seagoville camp.

All photos and clippings are larger when clicked.

*

Copyright © 2017 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

https://www.facebook.com/JanJarboeRussellTheTraintoCrystalCity

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] 2. “ENEMY ALIENS” AND THE WWII INTERNMENT CAMP AT SEAGOVILLE […]

LikeLike