by Paula Bosse

“From the Aboriginal Indians of this country — the early trappers — and pioneers learned that Rattle Snake Oil was the best remedy for rheumatism, pains, sprains, bruises, etc. Every cabin had its bottle hanging ready, from the rafters. The day will come when every house will have it again.”

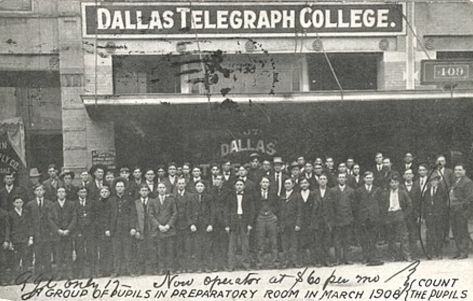

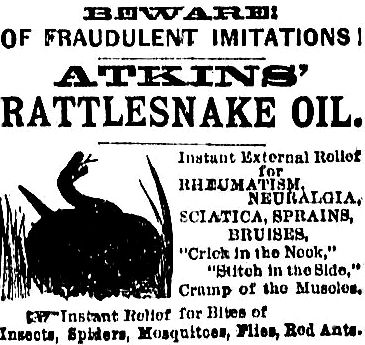

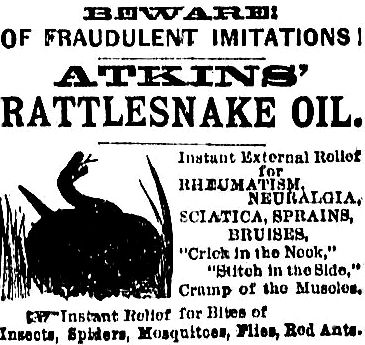

That little tidbit appeared under the heading “Folk-Lore” in the October 9, 1888 issue of the Dallas-based Southern Mercury newspaper. As there was no company name or product attached, it appeared to be a mere space-filling “factoid” rather than an advertisement. Conveniently, though, it was just a hop, skip, and a jump across three ink-smeared pages from a large ad for Atkins’ Rattlesnake Oil, an ad that warned the reader to “Beware of Fraudulent Imitations!” before it launched into a long list of testimonials from the once-weak and infirm. The ad ended with “Geo. T. Atkins, Dallas, Texas — For Sale by All Druggists.”

Southern Mercury, Oct. 9, 1888 (detail)

Southern Mercury, Oct. 9, 1888 (detail)

*

George T. Atkins was born in New York in 1837. Educated and having the bearing of a “trained businessman,” he drifted south and for some reason decided to join the Confederate army.

He was described by a fellow brigade member as a dark and handsome “compactly built” snappy dresser who “talked in a louder tone than the others, and [had] a peculiarly non-chalant, devil-may-care manner [that] emphasized his presence.” Atkins became a captain and quartermaster in the Fourth Kentucky Cavalry and though his position did not require participation on the battlefield, he was painted as something of a hot-dogging thrill-seeker: “[T]he gallant captain was frequently found in the ‘thickest of the fray,’ notably in the desperate battle at Saltville, where he recklessly and conspicuously rode up and down the lines, seeming determined to get himself killed.”

After the war, he eventually made his way to Texas with his family, arriving in Dallas in 1876 and settling into a large house at Ross Avenue and Masten Street (now St. Paul). At some point he opened a drugstore on Elm which seems to have been quite a successful enterprise. Perhaps it was his close proximity to drugs and medicinal compounds that prompted Atkins to launch his lengthy (and presumably lucrative) side-business as a snake oil manufacturer and salesman.

As far as I can tell, his “rattle snake oil” ads started around 1888. “Snake oil” has become a synonym for fraudulent wares sold by hucksters who know their products are ineffective but figure they can make a quick buck by grossly exaggerating — if not outright lying about — the magically curative properties of whatever it is they’re selling. As an actual “druggist,” Atkins probably had at least a little credibility compared to the other latter-day medicine-show men flogging their tonics and elixirs out of the back of a wagon before the law ran them out of town.

Southern Mercury, 1890 (det)

Southern Mercury, 1890 (det)

In fact, Atkins was, himself, such an expert flogger that his claim in ads that the United States Patent Office had officially ruled that his rattlesnake oil was “The Only True and Genuine Rattlesnake Oil” is automatically suspect, even though the editors of the Dallas Morning News (who, by the way, were no stranger to the popular and socially prominent Atkins, a man with, let’s not forget, a hefty newspaper advertising budget) published in its pages the following blurb (probably supplied by “the plaintiff”):

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 12, 1888

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 12, 1888

1888 was a good year, and Atkins was riding a snake-oil wave of good publicity. There were even reports in the local papers that Dallas’ favorite herpetologically-inclined drugstore owner was hustling “live and uninjured rattlesnakes” to interested parties in Paris and London. I don’t know … maybe…. Probably just some more creative publicity.

DMN, June 3, 1888

DMN, June 3, 1888

Atkins continued to run his drugstore and sell his snake oil until 1892 when, out-of-the-blue, he was assigned to dig the Texas Trunk Railroad out of receivership. The appointment seemed a little odd, but Atkins was a savvy businessman and a charming and persuasive speaker (he occasionally spoke in front of the Dallas City Council in a manner described as “felicitous and lucid”) — he could easily have back-slapped his way into the job. Despite the fact that he had no background in the railroad business, he seems to have spent several fairly productive years in the position. (His son, by the way, legitimately worked his way up through the ranks of the M-K-T, from lowly freight clerk to powerful executive VP.)

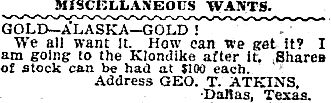

Eventually the railroad job ended and, in the waning years of the nineteenth century, Atkins seemed to be flailing a bit — he set the snake oil aside for a moment and placed an ad in the DMN classifieds soliciting investors to stake a claim in a Klondike gold scheme — at a mere $100 a share!

DMN, Aug. 8, 1897

DMN, Aug. 8, 1897

He continued in the rattlesnake oil biz until at least 1907, but at some point that began to fade away (or his inventory finally ran out), and he and his wife began running a boarding house. By 1918, though, he was tired of being a landlord and, at the age of 80, Atkins was finally ready to retire.

DMN, Oct. 20, 1918

DMN, Oct. 20, 1918

The large 12-room house at Ross and Masten sold after spending a lengthy time on the market, and Atkins and his wife moved to Lemmon Avenue, where, ultimately, he died on August 8, 1920.

DMN, Aug. 9, 1920

DMN, Aug. 9, 1920

George T. Atkins placed COUNTLESS snake oil ads in newspapers for something like twenty years. Each ad had his name on it. Boldly. Proudly. And there’s nary a mention of the famous Atkins’ Rattle Snake Oil in his obit! That’s a shame, because, to me, that’s the single most interesting thing about the man. He was a career snake oil salesman! He was also one of Dallas’ very first advertising empresarios — an entrepreneur who had a natural flair for the creative hard-sell and knew how to wield it.

“TAKE NO SUBSTITUTE!”

*

Southern Mercury, Dec. 20, 1900 (click to enlarge)

Southern Mercury, Dec. 20, 1900 (click to enlarge)

***

Quotes about Atkins’ time in the Confederate army from Kentucky Cavaliers in Dixie, Reminiscences of a Confederate Cavalryman by George Dallas Mosgrove (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press/Bison Books, 1999 — originally published in 1895); pp. 116-117.

Atkins’ physical examination of his snake oil, published in Chemist and Druggist (1890) can be seen here.

More on the Texas Trunk Railroad here.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

Spoolroom of the Dallas Cotton Mills…

Spoolroom of the Dallas Cotton Mills…

Southern Mercury, Oct. 9, 1888 (detail)

Southern Mercury, Oct. 9, 1888 (detail)

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 12, 1888

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 12, 1888 DMN, June 3, 1888

DMN, June 3, 1888  DMN, Aug. 8, 1897

DMN, Aug. 8, 1897 DMN, Oct. 20, 1918

DMN, Oct. 20, 1918 DMN, Aug. 9, 1920

DMN, Aug. 9, 1920

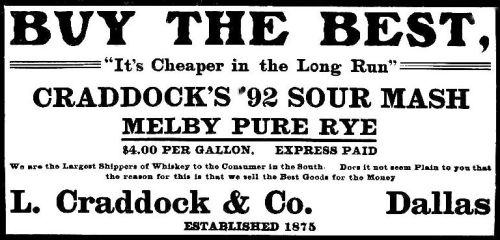

1908 ad

1908 ad