The Gateway to Junius Heights

by Paula Bosse

If you’ve driven along Abrams Road, between, say, Beacon and the Lakewood Country Club, you’ve probably passed two tall stone pillars which stand across Abrams from one another, and you’ve probably asked yourself, “What are those things?”

These things:

Google Street View here

Google Street View here

They were built as gateway markers to the Junius Heights neighborhood in about 1909 — they’re just not in their original location anymore. They were originally on either side of Tremont Street, half a block east of Ridgeway. They’ve been moved, but they’re only a stone’s throw from their original site.

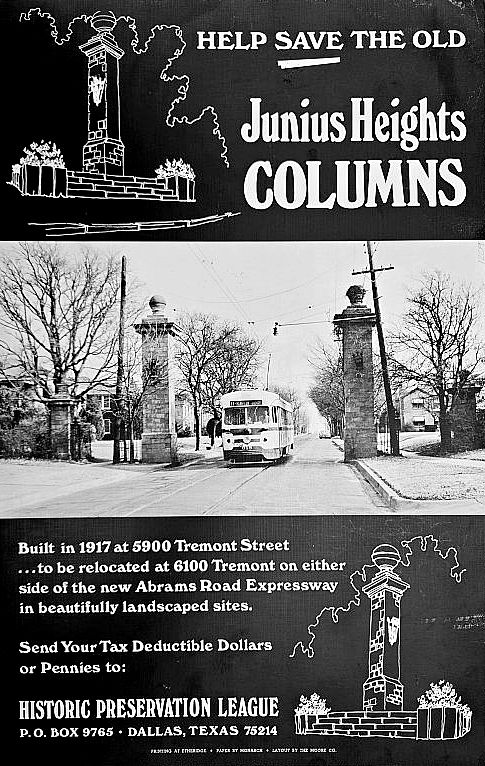

In 1973, when the city was in the midst of widening and connecting Abrams with Columbia, the 30-foot pillars were situated on a roadway which was going to be demolished. The pillars would have been destroyed were it not for the efforts of a small group of preservation-minded neighborhood residents who managed to raise enough money to have the historic East Dallas structures dismantled and moved. It took a while for the money to be fully raised, but the pillars were placed on their new sites in 1975.

The thing that is most interesting about the saving of these columns is that this took place at a time when this part of East Dallas — Swiss Avenue included — was on something of a downslide. Many of the houses were in disrepair and many residents had moved out, seeking newer homes and better (i.e. newer) neighborhoods. Thankfully, in the early 1970s people began to focus on historic preservation, and the area began to make a slow comeback. Thanks to the preservation efforts of these people, their persistence in gaining “historic district” status for Junius Heights and Munger Place, and their successful fights on zoning issues, the areas surrounding these stone pillars are once again highly desirable neighborhoods, full of homeowners who are good caretakers and thoughtful preservationists.

**

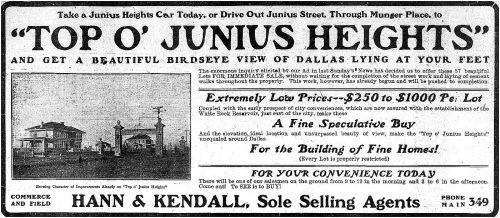

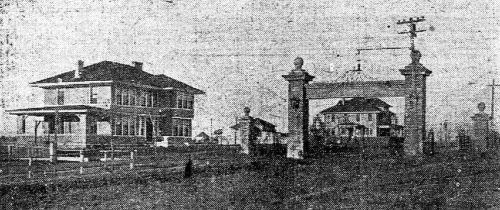

When researching this post, it was very difficult to determine when the pillars had been built. For some reason 1917 seemed to be a popular guess, and it was repeated in several articles I came across. But it was actually earlier. The earliest photo I’ve found (and I was pretty excited to have stumbled across it!) was one that first appeared in a November, 25, 1909 ad for a new development called “Top o’ Junius Heights.” (All photos and clippings are larger when clicked.)

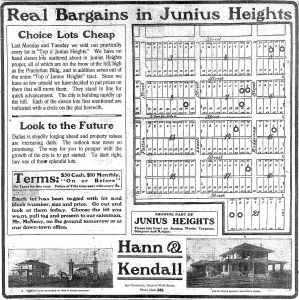

Here’s the full ad:

Dallas Morning News, Nov. 25, 1909

Dallas Morning News, Nov. 25, 1909

Note how similar this entrance looks to the entrance to Fair Park from the same time:

The same photo was used in another ad a few months later. If you live in Junius Heights, perhaps you can find your house in the diagram:

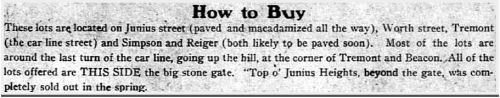

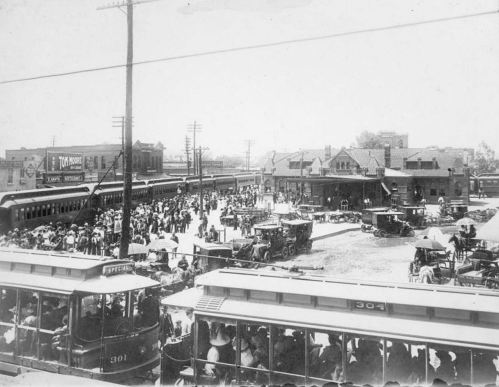

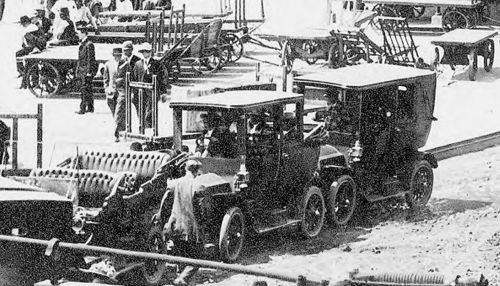

The pillars were actually built as a gateway — the columns connected at the top, spanning Tremont. Lots in Junius Heights first began to be sold in 1906; in 1909, the second addition — called “Top o’ Junius Heights” — began to be offered for sale. The opening of the second addition appears to be when the gateway might have been built. Not only did this gate serve as an entrance to Junius Heights, it actually separated the two additions (see clippings below). It was also a handy landmark, and for many years it stood at the end of the Junius Heights streetcar line (which ended at Tremont and Ridgeway).

Below, part of an ad for Top o’ Junius Heights that appeared in The Dallas Morning News on Nov. 28, 1909, in which the “big stone gate entrance” is mentioned:

Part of another ad for Top o’ Junius Heights:

And part of an ad for just plain ol’ Junius Heights, mentioning that the gate can be seen as a boundary:

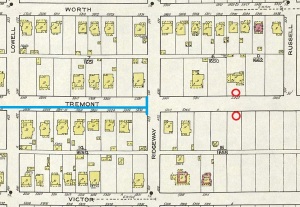

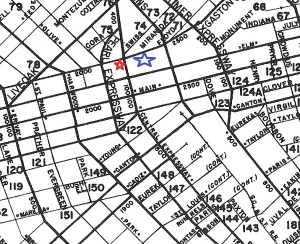

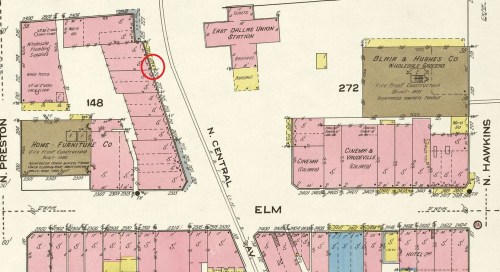

Here’s a detail from a 1922 Sanborn map which might make the location of the gate a little easier to visualize (and, again, these streets no longer look like this): the blue line represents the streetcar line (which ran all the way to Oak Cliff — the photo at the top of this post shows the Hampton streetcar), and the red circles are about where the pillars were originally planted. (The full map is here.)

It was pretty exciting finding that photograph from 1909, but it was also pretty exciting seeing a photograph posted in the Dallas History Facebook group by Jerry Guyer which shows a dreamy-looking view of the gate as seen from the yard of the home owned by his great-uncle, A. P. Davis, who lived at 5831 Tremont between 1911/12 and 1921/22 (see what the house looked like back then, here). The house was on the northwest corner lot of Tremont and Ridgeway (it is still standing), only half a block away from the gate. This detail of that photo is fantastic!

*

Another very early photo of the pillars/columns/gateway can be seen in this photo. (I’m afraid it’s a little odd-looking as I took a photo of it on the wall of The Heights restaurant in Lakewood and lights are reflecting off the picture. Please check this large photo out in person. Not only are there other great historical photos on the walls, but the coffee is great.)

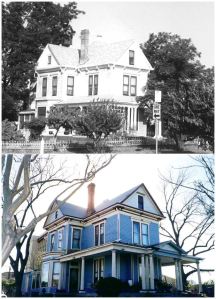

Here is the same photo as the one at the top. Note that this “gateway” has actual iron gates and that there are smaller secondary pillars on the opposite side of the sidewalks. Also note that the pillar on the right actually extends into the narrow street.

And here’s another view I just came across (I’ve added so much since I originally wrote this post!), from a DVD called Dallas Railway & Terminal — this from 1951 or 1952, showing the Junius streetcar coming through the “gates” (sorry for the low-res):

***

Sources & Notes

Top photo is from the Texas/Dallas History & Archives Division, Dallas Public Library (with special thanks to M C Toyer); DPL’s call number for this photograph is PA87-1/19-59-193.

Photo of the view of the gate from the home of Andrew P. Davis is from the collection of Jerry Guyer, used with permission.

More info on Junius Heights and the saving of the pillars can be found on the Preservation Dallas site, here. Here is a poster from the Dallas Public Library Poster Collection (with an incorrect date on it….).

A few Dallas Morning News articles on the fight to save the pillars:

- “Residents Try Saving Pillars From the Past” by Lyke Thompson (DMN, May 30, 1973, with photo of pillar)

- “Columns Come Down” (DMN, June 2, 1973, with photo)

- “Cash Raised for Pillars” (DMN, June 7, 1973)

- “Cornerstone Placed In East Dallas Area” by Michael Fresques (DMN, July 29, 1973, no photo, but description of pillars lying in pieces, awaiting funds to reconstruct them)

- “Junius Dedicates Columns” by Doug Domeier (DMN, June 16, 1975, pillars finally relocated, with photo of preservationist Dorothy Savage standing beneath one of the pillars)

East Dallas and Old East Dallas are fiercely proud of their history and fight for preservation issues.

*

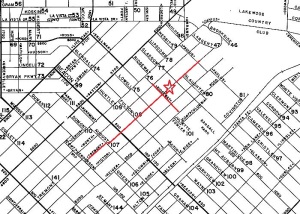

It’s a bit difficult for me to visualize where these pillars were originally. Here’s a 1952 map showing Tremont with the approximate location of the columns before they were moved.

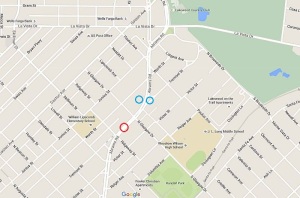

And here’s a present-day map, showing the post-Abrams extension. I’m not sure exactly where those pillars originally stood, but it was near the intersection of Tremont and Slaughter seems to have been between Ridgeway and Glasgow (location edited, thanks to Terri Raith’s helpful comments below) — this location is circled in red on the map below; the locations of the pillars today are in blue.

*

Copyright © 2016 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

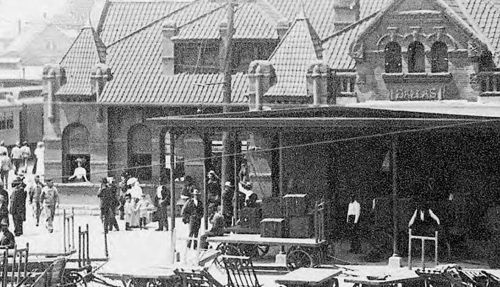

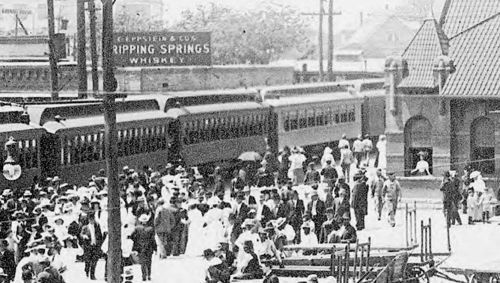

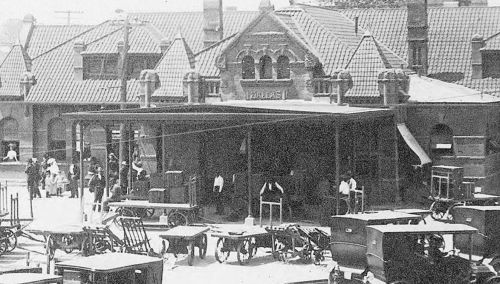

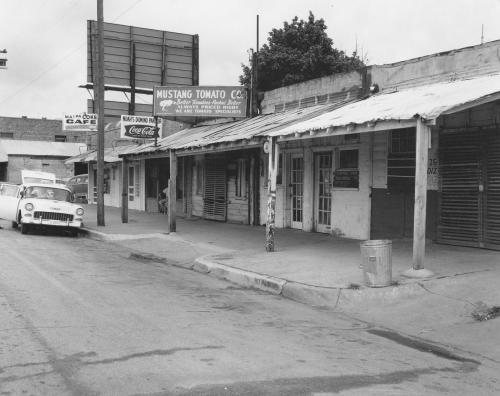

Squire Haskins, Nov. 1955, UTA Special Collections

Squire Haskins, Nov. 1955, UTA Special Collections

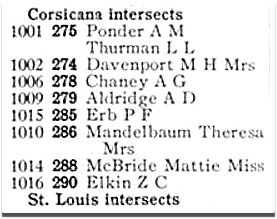

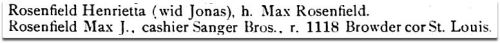

1911 directory,

1911 directory,

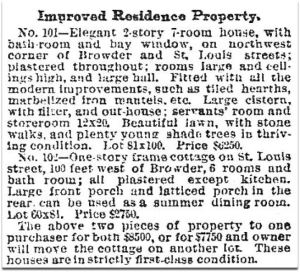

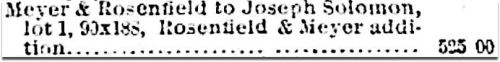

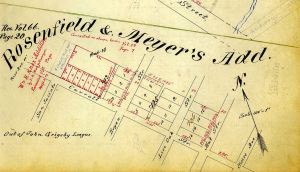

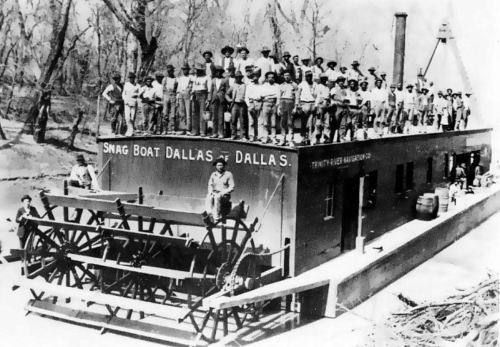

Galveston News, Mar. 24, 1883

Galveston News, Mar. 24, 1883 Galveston News, Mar. 24, 1883

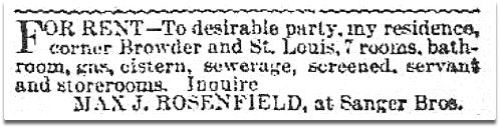

Galveston News, Mar. 24, 1883 Galveston News, July 2, 1883

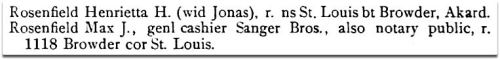

Galveston News, July 2, 1883 1886 Dallas directory

1886 Dallas directory

1888 Dallas directory

1888 Dallas directory DMN, Feb. 13, 1889

DMN, Feb. 13, 1889 1889 Dallas directory

1889 Dallas directory 1889 Dallas directory

1889 Dallas directory 1891 Dallas directory

1891 Dallas directory 1897 Dallas directory

1897 Dallas directory

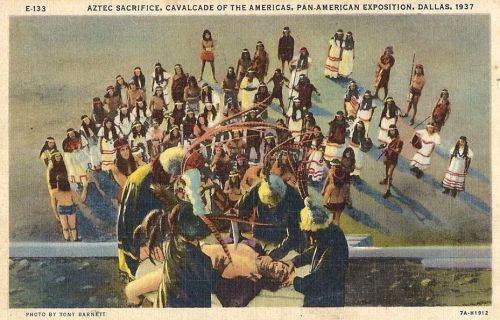

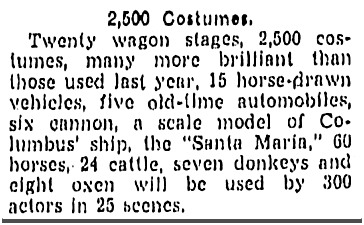

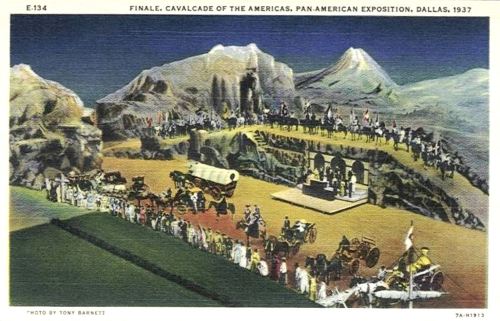

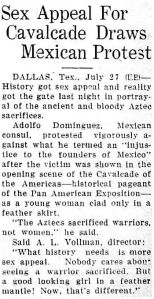

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 6, 1937

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 6, 1937

FWST, May 21, 1970

FWST, May 21, 1970

DMN, Jan. 15, 1893

DMN, Jan. 15, 1893

DMN, May 28, 1897

DMN, May 28, 1897