Einstein at the switch, June 12, 1937…

Einstein at the switch, June 12, 1937…

by Paula Bosse

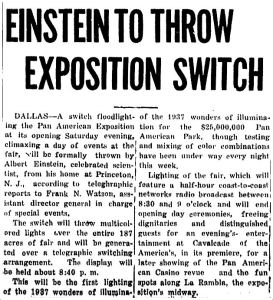

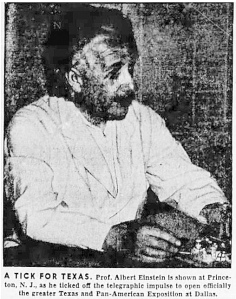

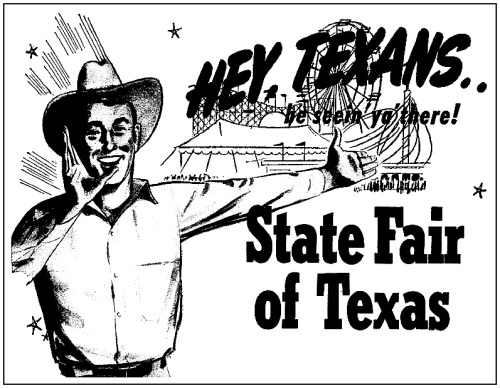

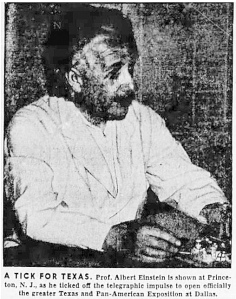

Who knew? Albert Einstein, the world’s most famous physicist, helped open the Greater Texas and Pan-American Exposition. The exposition was held at Fair Park for 20 weeks, from June 12, 1937 to October 31, 1937, as a follow-up of sorts to the Texas Centennial (the city had built all those new buildings — might as well get their money’s worth!). I’m not quite sure how Einstein got roped into this, but looking at the photo above, he seemed pretty happy about what was, basically, a long-distance ribbon-cutting. Via telegraph.

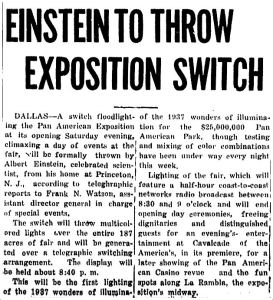

The plan was for Professor Einstein to officially open the Pan-American Exposition by “throwing the switch” which would turn on massive displays of lights around Fair Park. He would do this from Princeton, New Jersey, where he lived, by closing a telegraph circuit which would put the whole thing in motion. Newspaper reports varied on where exactly Herr Einstein was tapping his telegraph key — it was either the study in his home, in his office, in a Princeton University administration building, or in the Princeton offices of Western Union (the latter of which was mentioned in only one report I found, but it seems most likely).

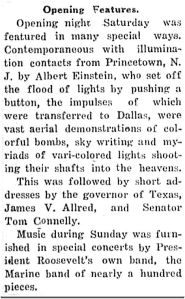

Einstein was a bona fide celebrity, and this was national news — newspapers around the country ran stories about it, and the ceremony was carried live on coast-to-coast radio. Almost every report suggested that Einstein’s pressing of the key in New Jersey would be the trigger that lit up the park in Texas, 1,500 miles away — which was partly correct. According to The Dallas Morning News:

Lights on the grounds will be turned on officially at 8:40 p.m. when Dr. Albert Einstein, exponent of the theory of relativity, presses a key in his Princeton home to fire an army field gun. With the detonation of the shell, switches will be thrown to release the flood of colored lights throughout the grounds. (DMN, June 10, 1937)

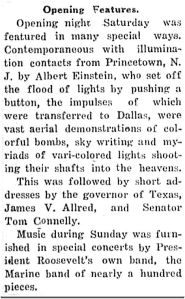

So on June 12, 1937 he pressed a telegraph key somewhere in Princeton, NJ, an alert was instantly wired to Dallas, an army field gun (in some reports a “cannon”) was fired, and that blast was the cue for electricians positioned around the park to throw switches to illuminate the spectacular displays of colored lights.

The Western Union tie-in gimmick was a success. Newspaper reports might have been a little purple in their descriptions, but from all accounts, those lights going on all at once was a pretty spectacular sight.

Dr. Albert Einstein, celebrated scientist, threw a switch that flashed a million lights over the 187-acre exposition park. The flash came at 8:40 o’clock and instantly the huge park became a city of a million wonders. Flags from a thousand staffs proclaimed their nationality [and] bands played the national airs of the nations of the Western Hemisphere as lusty cheers roared with thunderous approval. The Greater Texas and Pan-American Exposition was formally opened. It is on its way. (Abilene (TX) Reporter News, June 13, 1937)

The Dallas News describes the crowd as stunned into silence:

The waiting participants in the ceremonies at Dallas heard the results [of Einstein’s telegraph signal] when a cannon boomed. Electricians at switches around the grounds swung the blades into their niches and the flood of light awoke the colors of the rainbow to dance over the 187-acre park. Its breath taken by the spectacle, the crowd stood silent for a moment, and then broke into a cheer. (“Pan-American Fair Gets Off to Gay Start” by Robert Lunsford, DMN, June 13, 1937)

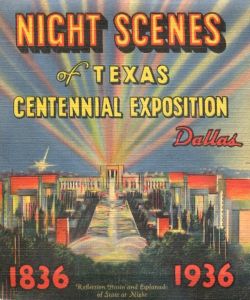

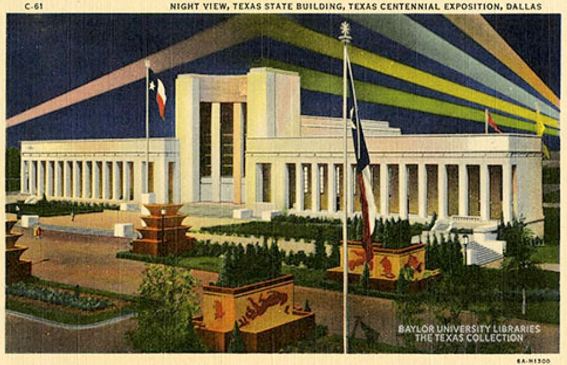

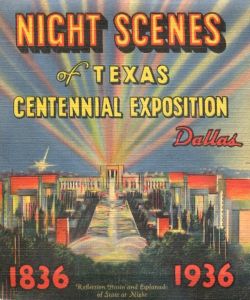

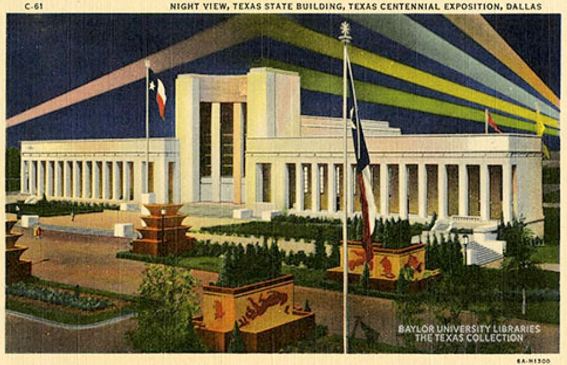

Many of the lighting designs and displays had been used the previous year during the Centennial, but, as with much of the attractions and appointments throughout the park, they were improved and spectacularized for the Pan-American Expo. And people loved what they saw.

Despite the multi-million dollar structures, air conditioning demos, works of art and other newfangled additions to the space, when people left the Centennial Exposition one thing was on everyone’s tongues, according to historical pollsters: the lights.

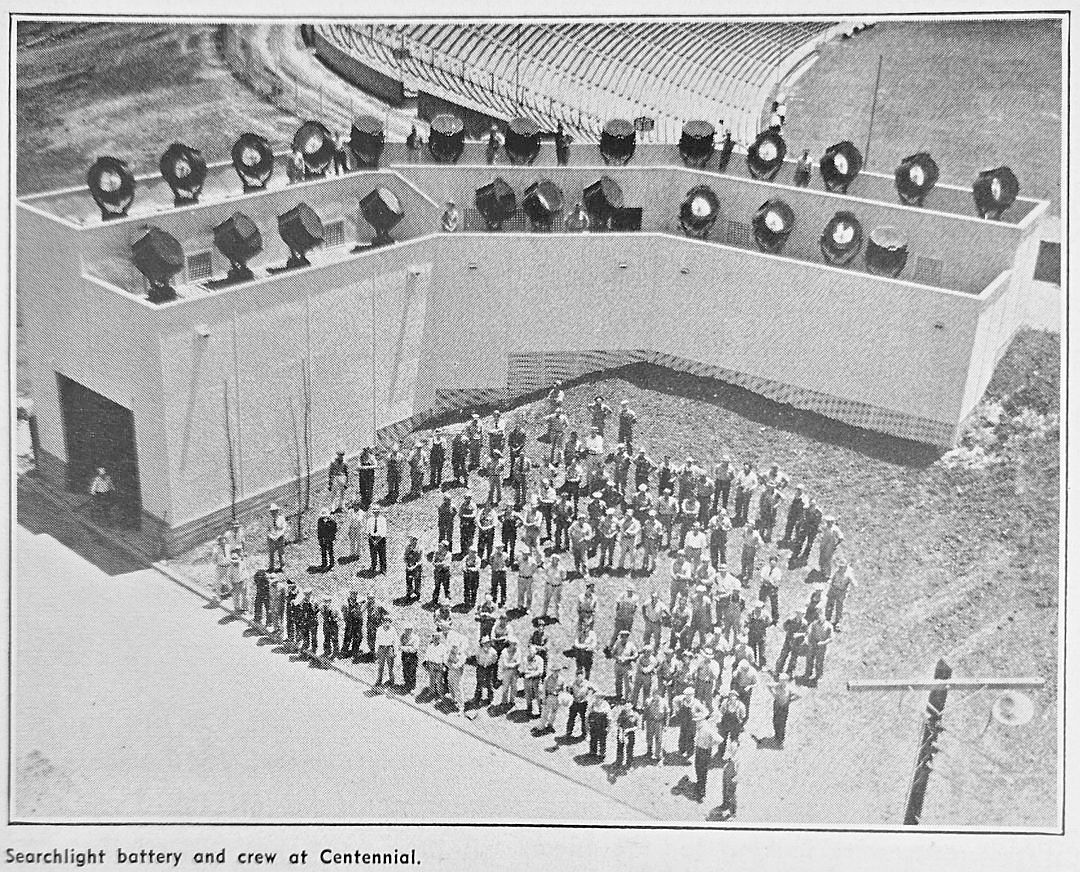

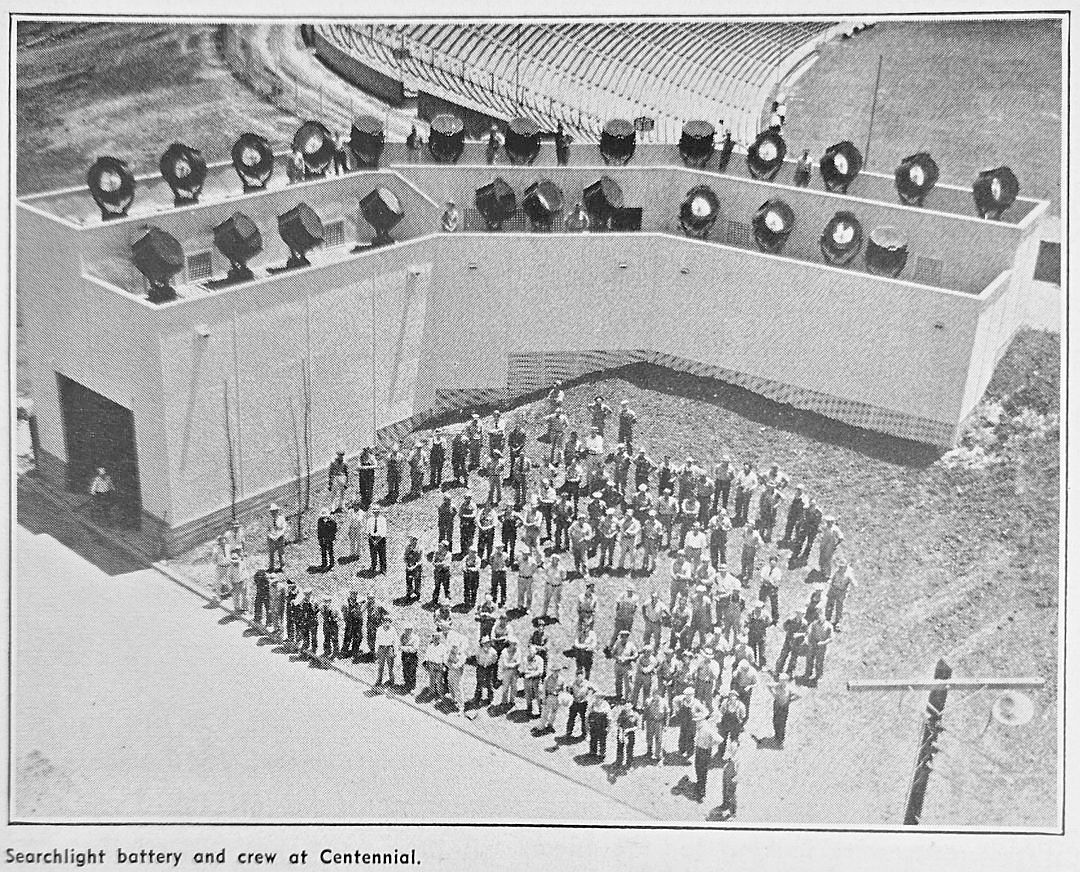

Positioned behind the Hall of State were 24 searchlights scaffolding into a crowned fan shape. “They all moved and were different colors,” says [Jim] Parsons [co-author of the book Fair Park Deco]. “It sounds gaudy, but people loved it.” The lights, he goes on to tell, were visible up to 20 miles away.

Considering most of the people who were visiting the fairgrounds were coming from rural farming communities with no electricity, the inspiring nature of those far-reaching beams makes a lot of sense. (Dallas Observer, Nov. 7, 2012)

Thanks for doing your part for Dallas history, Prof. Einstein!

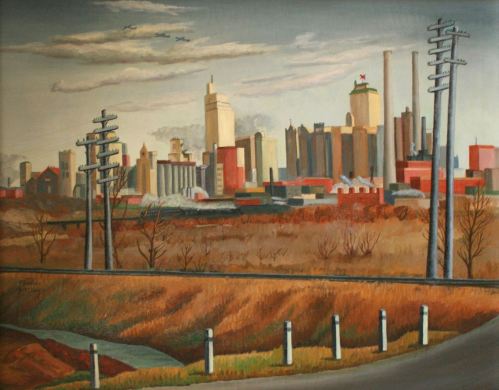

Below, photos from the Texas Centennial, 1936. The multicolored lights could be seen from miles away — here’s what they looked like from downtown and from White Rock Lake.

via Baylor University Flickr stream

via Baylor University Flickr stream

*

A look behind the scenes: “The general lighting effect is a battery of twenty-four 36-inch searchlights as powerful as the giants that flash from the dreadnoughts of Uncle Sam’s navy. Each searchlight will produce 60 million candlepower. Combined, the battery has a total candlepower of 1.5 billion. A 350,000-watt power generator will produce this colossal quantity of ‘juice.’” And the accompanying photo of the searchlight battery crew manning the candlepower:

Southwest Business, June 1936

Southwest Business, June 1936

**

(All pictures and clippings are larger when clicked.)

Denison Press, June 9, 1937

*

Waxahachie Daily Light, June 11, 1937

*

Denison Press, June 14, 1937

*

Medford (Oregon) Mail Tribune, June 23, 1937

*

Vernon Daily Record, June 24, 1937

*

1937

***

Sources & Notes

Top photo from the old Corbis site.

Black-and-white photos from the Centennial seen from Fair Park and White Rock Lake are from the Texas/Dallas History and Archives Division of the Dallas Public Library; the photo of the lights seen from downtown Dallas (titled “New skyline at night from Dallas, Texas”) is from the GE Photo Collection, Museum of Innovation and Science (more info on that photo is here).

Sources of other images and clippings cited, if known.

More on the Pan-American Exposition from Wikipedia, here, and from the fantastic Watermelon Kid site of all-things-Fair-Park, here.

*

Copyright © 2016 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.