The John E. Mitchell Company’s WWII Munitions Work (Part 1)

by Paula Bosse

The John E. Mitchell Company arrived in Dallas in 1928 to join the other nearby manufacturers of cotton gins and other agricultural equipment. They built their factory at 3800 Commerce, between Benson and Willow Streets, in the area now commonly referred to as Exposition Park, a few blocks from Fair Park. (The building still stands and has been converted into lofts. More on the building itself in Part 3.)

In 1942, during World War II, the large cotton machinery factory gradually transformed itself into one wholly concerned with war production, primarily manufacturing munitions for the Navy, but also producing ordnance parts for the Army.

Below are a series of postcards, produced by the Mitchell Company, touting their contribution to the war effort and acknowledging their workers. The second half of these cards will be contained in the next post. (Most of the cards are larger when clicked.)

*

The top card shows part of the plant’s inspection department:

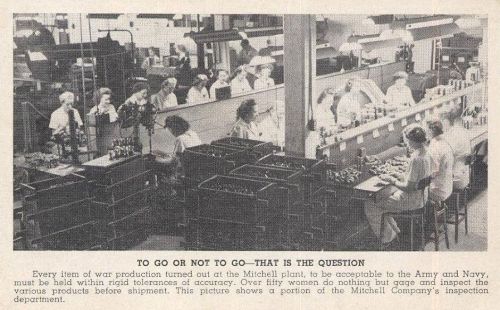

TO GO OR NOT TO GO — THAT IS THE QUESTION

Every item of war production turned out at the Mitchell plant, to be acceptable to the Army and Navy, must be held within rigid tolerance of accuracy. Over fifty women do nothing but gage and inspect the various products before shipment. This picture shows a portion of the Mitchell Company’s inspection department.

*

DALLAS FIRM AWARDED FIFTH ARMY-NAVY “E”

The John E Mitchell Company of Dallas Texas announced receipt of its fourth renewal of the Army-Navy E award, the fifth presentation, counting the original flag.

John E Mitchell, Jr., president, said so far as he knew the firm was the first in this section of the country to have received five awards, each representing six months of continued production excellence. The award came from Adm. C. C. Bloch, chairman of the navy board of production awards in Washington.

Employees of the Mitchell company have a record of 100 per cent participation in weekly purchases of war bonds, and the average for all employees is above 12 per cent. Absentees, excluding authorized absences, run less than 1 per cent.

From the Daily Times Herald, Tuesday, March 20, 1945

*

KEEPING IT IN THE FAMILY

There are not many families in the country making as much of a contribution to the war effort on the production front as are the Gardners. Here they are, eight of them, all engaged in vital war work in the Mitchell plant.

Left to right: Ernest, Nettie, Fred, Ida, Raymond, Pearl, Herbert, and Maxine.

*

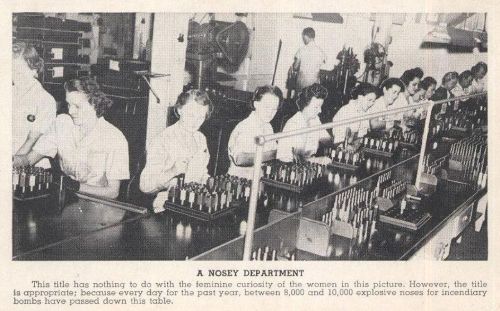

A NOSEY DEPARTMENT

This title has nothing to do with the feminine curiosity of the women in this picture. However, the title is appropriate; because every day for the past year, between 8,000 and 10,000 explosive noses for incendiary bombs have passed down this table.

*

PERPETUAL MOTION

This view, taken inside the Mitchell factory, shows a portion of our lathe department. Most of these lathes operate 24 hours a day, and most of them are now turning out Navy items for the Pacific War against Japan.

*

BIG JOKE

When this picture was taken, our president, John Mitchell, had evidently pulled off some sort of wisecrack which everyone seemed to enjoy, especially Mr. Mitchell himself.

The scene: one of the Mitchell Company’s regular Monday assembly meetings. The honored guests: Barney Kidd and Raleigh Smith, former Mitchell employees, now representing their company in both branches of the armed services.

*

MEET OUR INDUSTRIAL CHAPLAIN

Let us introduce you to Art Isbell, the Mitchell Company’s industrial chaplain, shown here consulting with receptionist Doris Aday.

One of the first concerns in the nation to retain a full time industrial chaplain, the Mitchell Company has already discovered how important his services can be. Handling funeral arrangements, visiting the sick, helping with personnel problems, rendering spiritual guidance, Art Isbell has made himself invaluable to Mitchell men and women and has already endeared himself to the hearts of many through his patient understanding and never-failing cooperation.

*

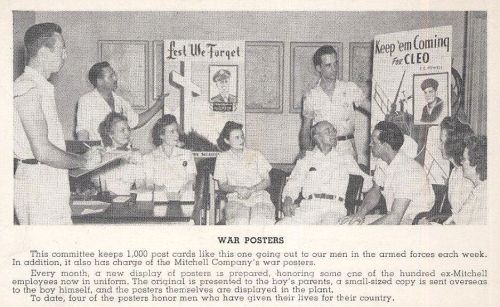

WAR POSTERS

This committee keeps 1,000 post cards like this one going out to our men in the armed forces each week. In addition, it also has charge of the Mitchell Company’s war posters.

Every month, a new display of posters is prepared, honoring some one of the hundred ex-Mitchell employees now in uniform. The original is presented to the boy’s parents, a small-sized copy is sent overseas to the boy himself, and the posters themselves are displayed in the plant.

To date, four of the posters honor men who have given their lives for their country.

***

Sources & Notes

Postcards found on eBay last year. I was a little surprised to find that most of them are still available for purchase, here.

For more on the Mitchell Company’s early days as a munitions plant, see the Dallas Morning News article “E Award Given Plant Doing Munitions Job” (DMN, Dec. 29, 1942).

The Mitchell Lofts building is a long way from being war-time production plant. Here is what it looks like today.

Google Maps (click for larger image)

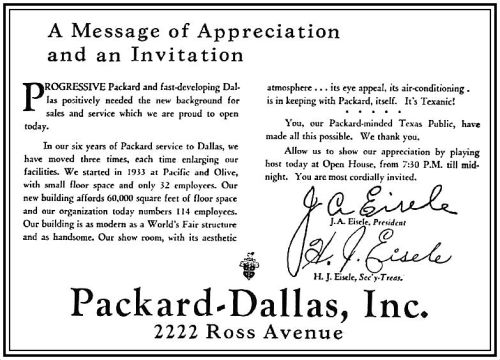

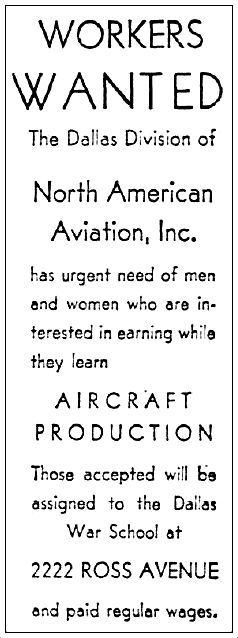

Another Flashback Dallas post on a local munitions plant (this one downtown) — “2222 Ross Avenue: From Packard Dealership to ‘War School’ to Landmark Skyscraper” — is here.

Part 2 features more of these postcards of the Mitchell Company’s war work, here.

Part 3 will focus on the building itself.

Check back!

*

Copyright © 2016 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

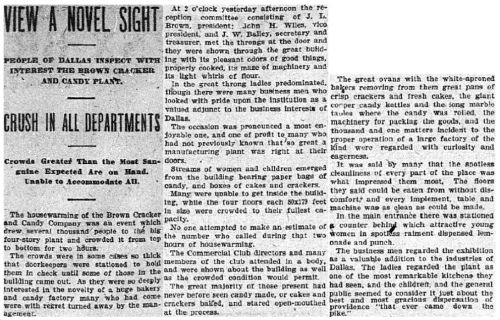

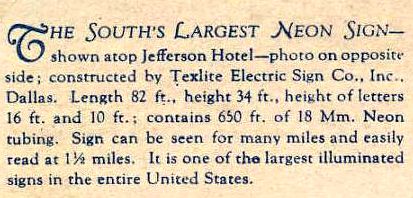

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 16, 1949

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 16, 1949

Dallas Morning News, Sept. 15, 1886

Dallas Morning News, Sept. 15, 1886 DMN, Sept. 30, 1888

DMN, Sept. 30, 1888

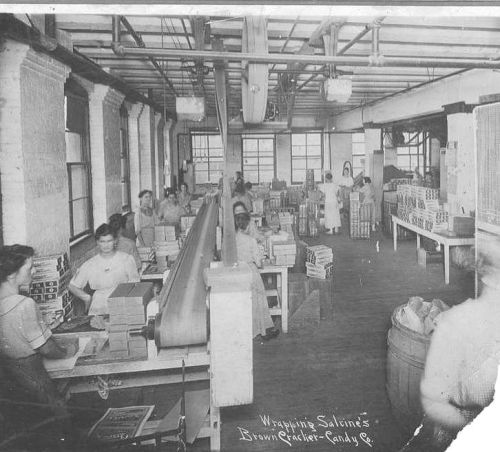

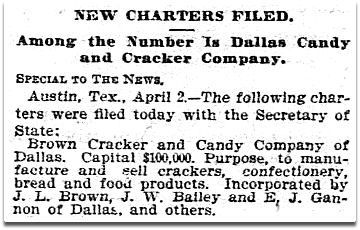

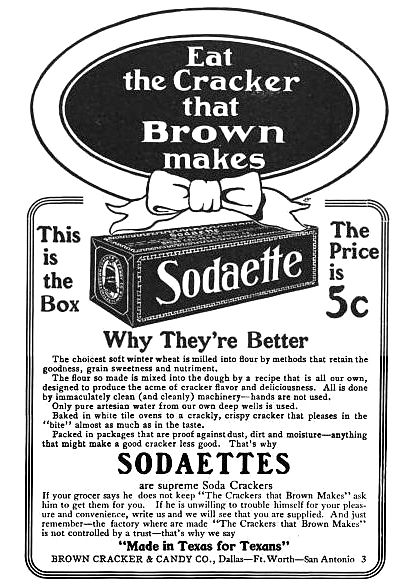

Dallas Morning News, April 3, 1903

Dallas Morning News, April 3, 1903

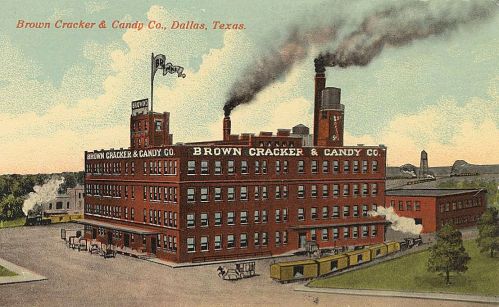

DMN, April 6, 1903

DMN, April 6, 1903

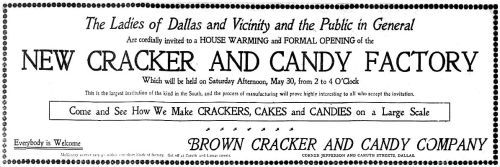

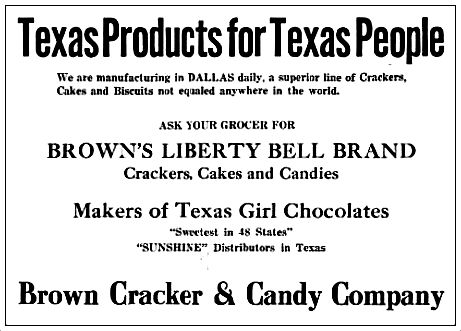

DMN, Dec. 20, 1903

DMN, Dec. 20, 1903

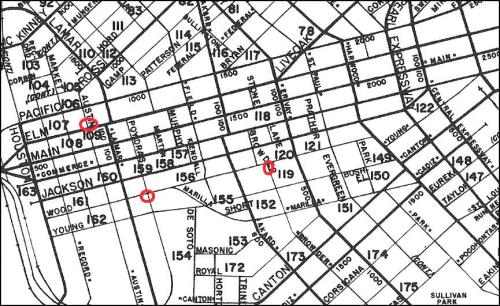

1922 city directory

1922 city directory

Bessie Manning’s occupation, 1920 census

Bessie Manning’s occupation, 1920 census

1948 city directory

1948 city directory

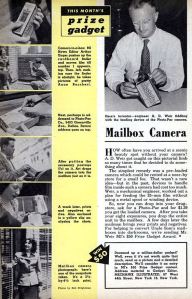

Sept. 1943

Sept. 1943