George W. Cook Collection/SMU

George W. Cook Collection/SMU

by Paula Bosse

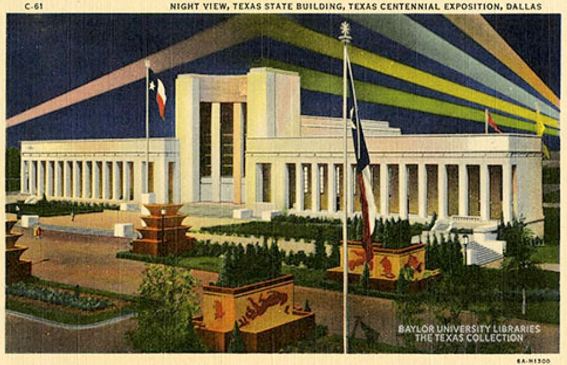

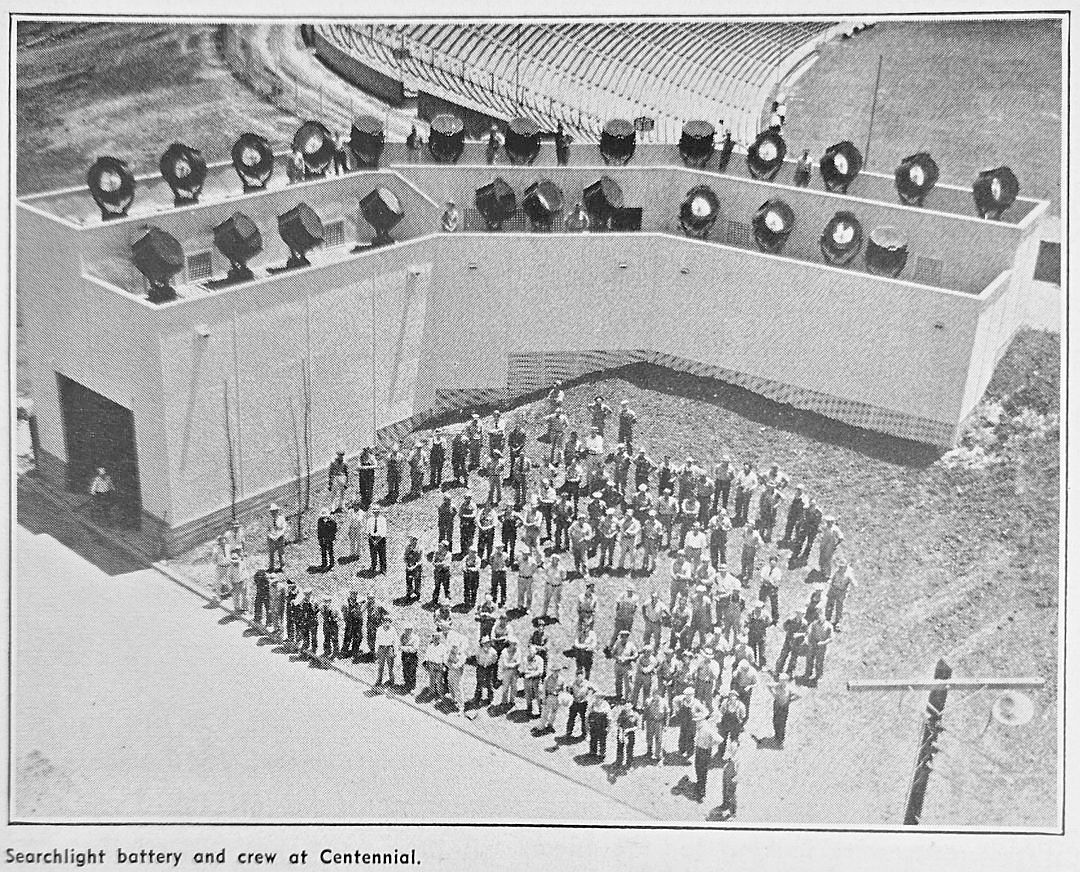

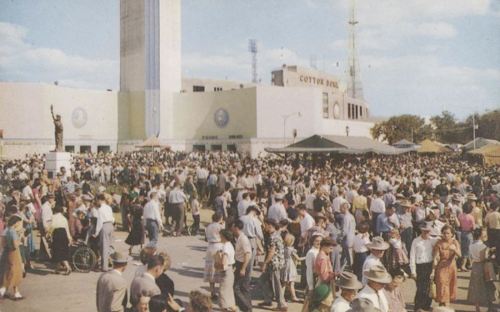

When one thinks of the Texas Centennial Exposition, the splashy 6-month extravaganza held at Fair Park to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Texas independence, one might not immediately think of the three things associated with the big show that were making headlines around the country (and were undoubtedly responsible for healthy ticket sales): according to Variety, the Centennial had “all the gambling, wining and girling the visitor wants” (June 10, 1936).

The Dallas exposition (and the coattail-riding Frontier Exposition, which was held at the same time in Fort Worth) was “wide open” in 1936: there was gambling, liquor, and nudity everywhere. The Texas Rangers cracked down on some of the gaming in the early days, but alcohol and girlie shows continued throughout the expo’s run.

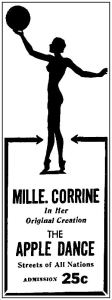

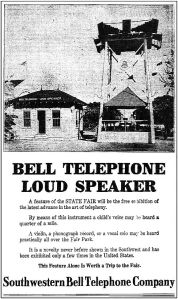

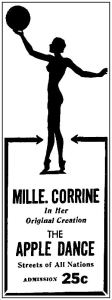

As far as the nudity, it really was everywhere. It’s a little shocking to think that this sort of thing was so widely accepted in very conservative Dallas — 80 years ago! — but it was (despite some local pastors disdainfully referring to the big party as the Texas Sintennial). Many of the acts — and much of the personnel — had appeared in a version of the same revue in Chicago in 1933 and 1934. Some of the offerings for the Centennial visitor: peep shows a-plenty, the clad-only-in-body-paint “Diving Venus” named Mona Lleslie (not a typo), a naked “apple dancer” named Mlle. Corinne who twirled with a “basketball-sized ‘apple'” held in front of her frontal nether regions, and the somewhat obligatory nude chorus girls. There was also an “exhibit” in which nude women were on display as “artists’ models,” posing for crowds of what one can only assume were life-drawing aficionados who were encouraged to render the scene before them artistically (…had they planned ahead and brought a pencil and sketchpad); those who lacked artistic skill and/or temperament were welcome to just stand there and gawk. (Click photos and ads to see larger images.)

Franklin, Indiana Evening Star, July 11, 1936

Franklin, Indiana Evening Star, July 11, 1936

Another attraction was Lady Godiva, who, naked, rode a horse through the Streets of Paris crowds. Her bare-breastedness even made it into ads appearing in the pages of staid Texas newspapers. (Click to see larger images.)

June, 1936

There were two areas along the Midway where crowds could find these saucy attraction: Streets of Paris (which Time magazine described as appealing to “lovers of the nude”) and Streets of All Nations (“for lovers of the semi-nude”). Lady Godiva was part of the Streets of Paris, and she rode, Godiva-esque, nightly. The gimmick (beyond the gimmick of a naked woman riding a horse in Fair Park) was that she was supposed to be a Dallas debutante who rode masked in order to conceal her identity. The text below is from the ad above.

MASKED…but unclothed in all her Glory…Riding a milk-white steed. […] Miss Debutante was introduced to Dallas society in 1930. She was later starred in Ziegfeld’s Follies, in “False Dreams, Farewell,” “Furnished Rooms,” and other Broadway successes. She appeared in motion pictures, being starred in “Gold Diggers of 1935,” “Redheads on Parade” (yes, she is a redhead) and other picture successes.

SHE WILL STARTLE DALLAS SOCIETY! JUST AS THE STREETS OF PARIS WILL BE THE SENSATION OF THE CENTENNIAL SEASON .. WHO IS SHE?

And, of course, none of that was true (including the fact that this “Lady Godiva” rode a white horse — apparently one could not always be found), but I’m sure it got local pulses racing. My guess is that there were several Ladies Godiva (none of whom were members of Dallas society). One woman was actually named as the Centennial’s exhibitionist horsewoman. I haven’t been able to find mention of a “Paulette Renet” anywhere other than the caption of this photo, but here she is:

Madera (California) Tribune, Aug. 29, 1936

Another photo featuring what appears to be the same woman, with this caption: “No white horse for Lady Godiva, at the Texas Centennial Exposition in Dallas. A feature of the ‘Streets of Paris,’ a midway show, Godiva rode a ‘paint pony,’ first week because no white one was available.”

Altoona (Pennsylvania) Tribune, June 23, 1936

I think this is still the same woman, but on a rare white steed:

The Godiva who appeared in the March of Times newsreel “Battle of a Centennial” appears to be a different woman. (Watch a 45-second snippet of the newsreel which features both a glimpse of Lady Godiva and a head-shaking son of Sam Houston wondering what the deal is with the younger generation — here.)

Imagine seeing performers and attractions like this along the Fair Park midway today!

*

July, 1936 (ad detail)

July, 1936 (ad detail)

June, 1936 (ad detail)

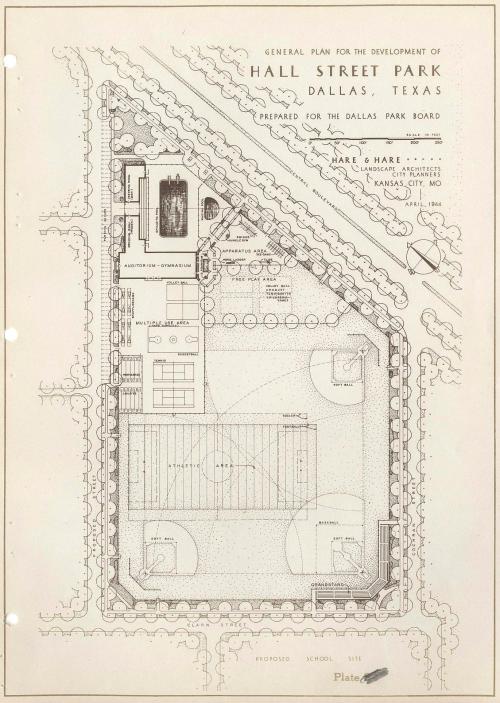

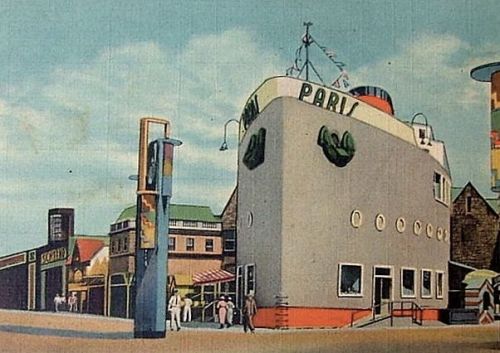

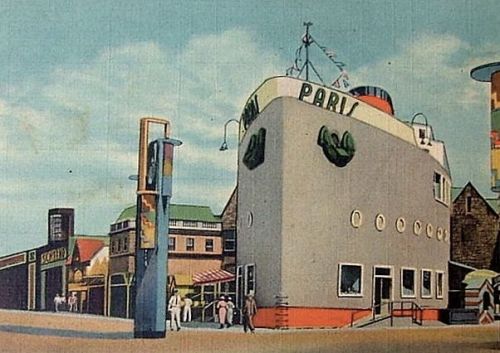

What was the Centennial Club? It was an exclusive, invitation-only private club located within the very large George Dahl-designed building which housed the Streets of Paris (and which was shaped like the famed S. S. Normandie ocean liner). It had three levels (“decks”) and housed a lounge, dining rooms, a main clubroom, and a “dance pavilion” — all air conditioned. From various decks, well-heeled patrons could look down at the action going on below: the milling throngs of the hoi polloi, the Streets of Paris shows, and the Midway.

June, 1936

Can’t miss the ridiculously large land-locked ocean liner in the center of the photo below. Mais oui!

**

The articles below on “gals, likker, and gambling” are GREAT. They are from the show biz trade publication Variety, which really latched onto the rampant nudity on view at the Texas Centennial. Remember: 80 years ago! (The abbreviation of “S. A.” in the headline of the second article stands for “sex appeal.”) (As always, click to see larger images.)

Variety, June 10, 1936

Variety, June 24, 1936

Variety, July 1, 1936

***

Sources & Notes

Top photo shows an admission ticket to the Streets of Paris, from the George W. Cook Dallas/Texas Image Collection, Central University Libraries, Southern Methodist University; more information is here. Another interesting item from this collection is a brochure (here) which describes Streets of Paris as “the smartest, most sophisticated night club in America. Here you will find the gay night life of Paris in a setting of exotic splendor.”

Photo of “Mlle. Corrine” also from the Cook Collection at SMU; more info on that photo here.

Photo of Lady Godiva on a white horse (with the words “Dallas Centennial” near the bottom … um, bottom of the image … is also from the Cook Collection at SMU, here.

The photo showing the night-time crowd outside the Streets of Paris Normandie is from the Ryerson & Burnham Archives, Art Institute of Chicago; more info here.

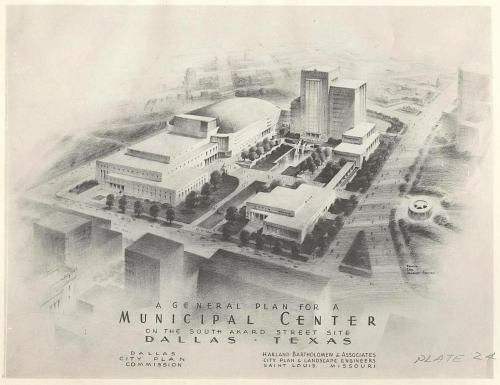

The aerial photograph showing the S. S. Normandie is from Willis Cecil Winters’ book Fair Park (Arcadia Publishing, 2010); photo from the collection of the Dallas Historical Society.

All other sources noted, if known.

See quick shots of the Streets of Paris and the Streets of All Nations in the locally-made short film “Texas Centennial Highlights,” here (Streets of Paris is at about the 7:00 mark and the more risqué bits showing the parasol chorus girls followed by Mlle. Corinne and her apple dance (I mean, it’s not really shocking, but … it still kind of is…) at the 8:45 mark. (Incidentally, there appears to be a new book on Corinne and her husband — Two Lives, Many Dances — written by their daughter.)

A very entertaining history of the State Fair of Texas and the Texas Centennial Exposition can be found in the article “State Fair!” by Tom Peeler (D Magazine, October, 1982), here.

A Flashback Dallas post on the feuding Dallas and Fort Worth Centennial celebrations can be found here.

More Flashback Dallas posts on the Texas Centennial can be found here.

Click pictures and clippings to see larger images.

*

Copyright © 2016 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

Behold… (click for larger image)

Behold… (click for larger image)