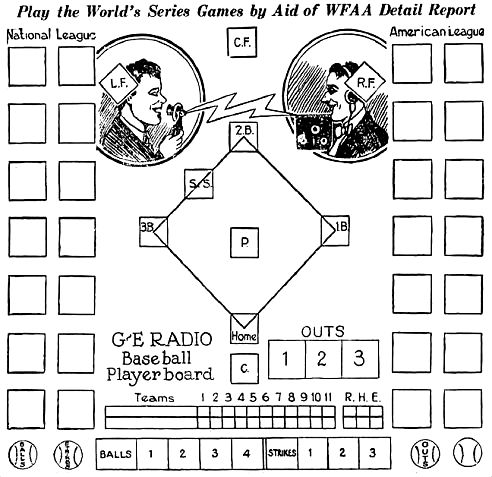

The later version, for radio listeners, 1922…

The later version, for radio listeners, 1922…

by Paula Bosse

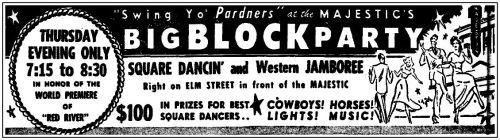

It’s 1912. You’re a huge baseball fan, and the World Series is about to begin — New York vs. Boston! But you live in Dallas, a million miles away from the action. You can’t wait for the results in the paper the next day because you’re an impatient S.O.B., and radio won’t be introduced for another ten years. Do you panic? No! Because you live in a big city with a taste for new technology, and the Dallas Opera House is going to present a sort of early simulcast of the games on a “mammoth automatic score board.” Your sports prayers have been answered!

DMN, Oct. 6, 1912

DMN, Oct. 6, 1912

You lean back in your comfy theater seat and smoke your smokes in plush and civilized surroundings as each play is sent by telegraph to Dallas from the ballpark back East where the game is being played RIGHT NOW, hundreds of miles away. The telegraph operator in Dallas will relay the play-by-play information to personnel in the theater who will somehow do something to some sort of “automatic electric board.” And, according to promoters of these “reproductions” of baseball games, you’ll feel like you’re right there in the thick of the action. You’ll “see” the game played before your eyes!

I’ve read several articles about these boards and these reproductions, but I can’t for the life of me figure out how it worked. I assume there was a large traditional scoreboard on stage that lit up, keeping track of the score, runs, outs, etc. But apparently there’s more, and I just can’t picture it. Here’s a somewhat confusing description of what happened during these productions:

WORLD SERIES WILL BE SHOWN AT THE OLD MILL

Manager Buddy Stewart of the Old Mill Theater announced that he secured the New Wonder Marvel Baseball Player Board to reproduce the World Series baseball games. This board is declared the greatest board ever invented for reproducing baseball games. It is not a mechanical board and no mechanical devices are used, and very little electrical appliances are necessary. The games are reproduced by a crew of six experienced baseball players who are carefully rehearsed and each has a part or position to play. No other board is so complete as this. The board does not require sign cards to denote players as in other boards. You see the ball going and do not have to look in any other direction to see what it means.

Spectators will see each play reproduced in less than two minutes after it is made on the playing fields of the World Series as the board is connected with a direct wire to the baseball field, and as fast as the telegraph operator receives the play it is reproduced with as much realism as on the field. The players are seen to run bases, the ball is seen bouncing or soaring to the infield or outfield, and anyone who is familiar with baseball will know just exactly what is happening on the field by the plays made on the board with very little left for imagination.

Every hit, run, error, strike or ball, the number of strikeouts, or balls made by pitchers, or the number of hits, runs or errors made by the players is always prominently shown on the board which makes it [un]necessary for individual scoring during the progress of the game. (DMN, Oct. 3, 1920)

Doesn’t really help much. It sounds as if people are on the stage acting out each play. That would be weird. These “reproductions” of World Series games were quite popular in Texas (and probably elsewhere) for at least 15 years. If anyone reading this has a photo or diagram of one of these vaunted Marvel scoreboards, I’d love to see it!

*

An earlier description of the 1912 Opera House reproduction sounds more like an audience watching a baseball game on a giant Lite-Brite “score board.”

DMN, Oct. 8, 1912

DMN, Oct. 8, 1912

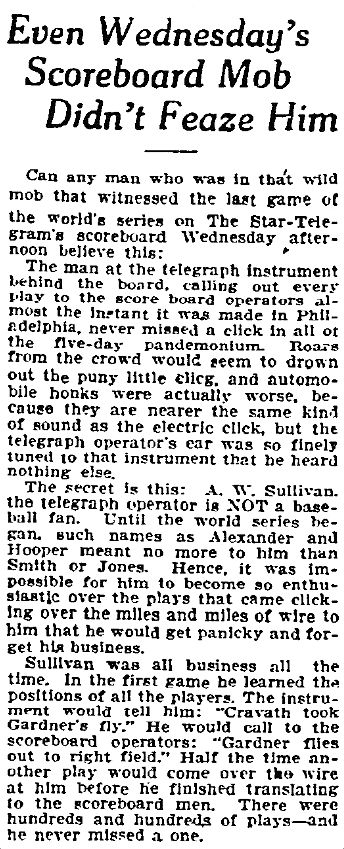

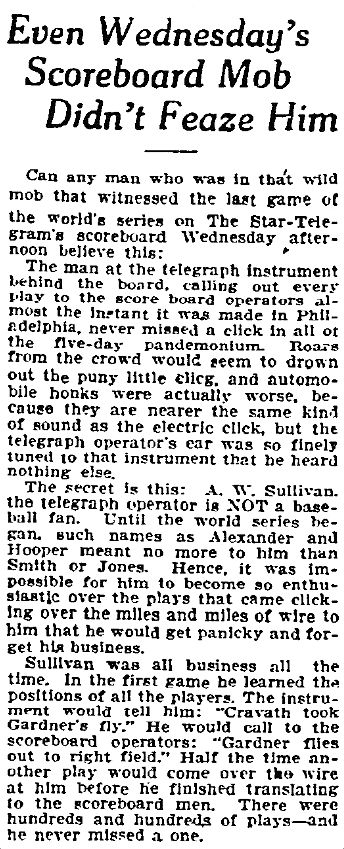

The trick to keeping the telegraph operators calm and on-their-toes during a lengthy baseball game? Make sure they have no interest in the game.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Oct. 14, 1915

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Oct. 14, 1915

Fort Worth was also getting in on the action. And they had celebrities — people like Clarence (Big Boy) Kraft and Ziggy Sears (who I’m going to assume have something to do with baseball). I’m not sure what these celebrities were doing exactly, but whatever it was, they were there doing it.

FWST, Oct. 2, 1921

FWST, Oct. 2, 1921

These theater programs weren’t for everyone, though. If you couldn’t take the time out of a busy work day to swan over to a theater to leisurely witness one of the early “reproductions” (or if the admission price was too steep for your budget), you could always ring up the operator to have her tell you the current score:

DMN, Oct. 11, 1912

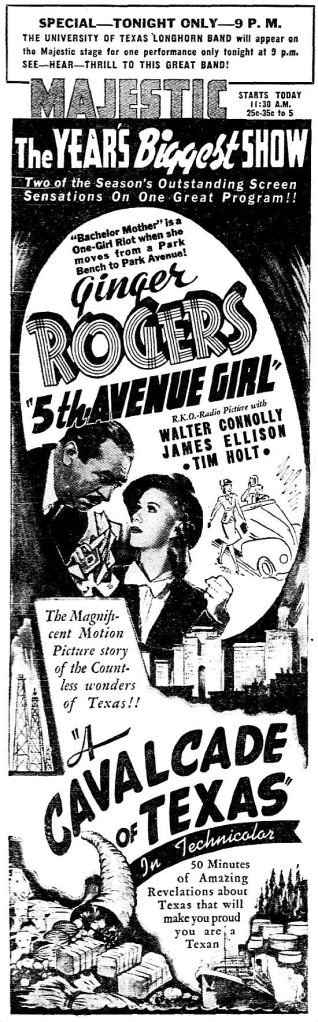

These things seemed to be a popular annual event, but in 1922, something more technologically advanced than the Marvel board appeared on the scene: radio! WFAA and WBAP began broadcasting in 1922, and, suddenly, following sports became a whole lot easier. In something of a transitional technology, there was the outdoor board as described below. The games were not only broadcast live on WFAA, but The Dallas Morning News (WFAA’s parent company) also erected one of those old-fangled “electric boards” out on the street so that passersby could keep up with the scores. (Portable transistor radios were decades and decades away.)

DMN, Oct. 10, 1923

DMN, Oct. 10, 1923

It was surprising to see that the “Marvel score boards” were still being used as late as 1926 (Yankees vs. Cardinals, at the Capitol Theater). Every baseball fan worth his salt should have had his own radio by then so he could listen to the World Series in the comfort of his own home and curse and cheer as loudly as the vicissitudes of the game demanded. Eat my dust, Marvel board! Radio changed everything, and radio was here to stay.

*

UPDATE: Thanks to Kevin’s link in the comments below, I can share this GREAT article from Uni-Watch.com about another of these boards called the Play-o-Graph: “Photography of Playography“ by Paul Lukas — it answers all my questions, and it even has photos (and links to photos) of crowds watching the boards. He also links to a 1912 article, “The Automatic Baseball Playograph” by J. Hunt, in the Yale Scientific Monthly which describes how the board works and has this photo:

The “Play-o-Graph,” 1912 (click for larger image)

The “Play-o-Graph,” 1912 (click for larger image)

And, for completists, here’s an ad for the Play-O-Graph, from 1913:

Billboard, Mar. 22, 1913

Billboard, Mar. 22, 1913

Makes a bit more sense now! Thanks, Kevin!

***

Sources & Notes

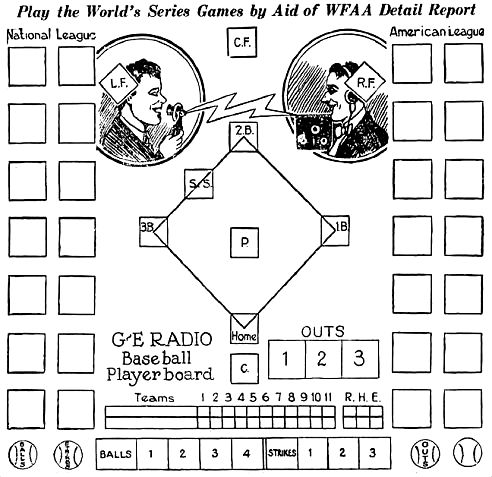

The top image is the “G.E. Radio Baseball Player Board” — a sort of home version of the big scoreboards used in theaters, printed for WFAA listeners in The Dallas Morning News on Oct. 4, 1922. The instructions are in a PDF, here. And feel free to print one out and use it while you watch the Series this year. Still works in the 21st century!

For an article on listener response to the successful first broadcast of the World Series by WFAA radio (listeners picked up the signal in England!), see the DMN article from Oct. 6, 1922 in a PDF, here.

And because they have such great names, you might want to know who Clarence “Big Boy” Kraft and Ziggy Sears were. If you’ve read this far, you owe it to yourself. “Big Boy,” here; Ziggy, here.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

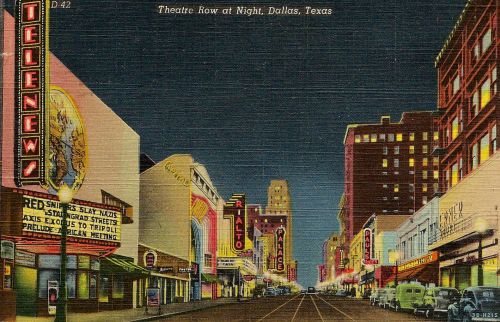

Photo by Joe Lawrence, circa 1915

Photo by Joe Lawrence, circa 1915 The Crystal Theatre — with office space above (click for larger image)

The Crystal Theatre — with office space above (click for larger image) 1914 — “Comfort & Refinement”!

1914 — “Comfort & Refinement”!

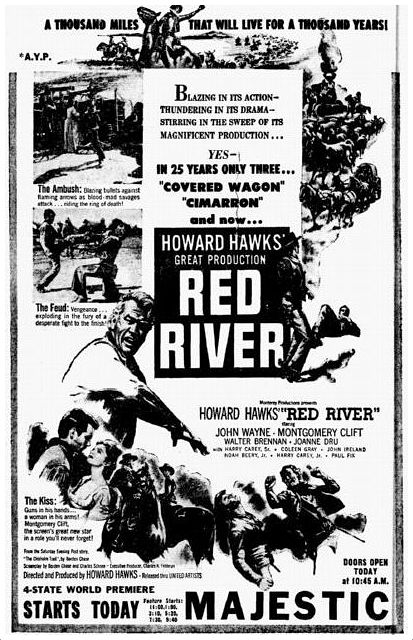

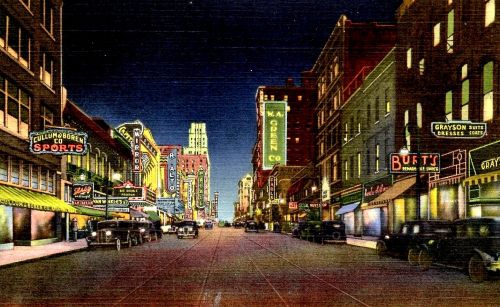

1952

1952