The Mitchell Building: Home to Cotton Gins, Rockets, Frozen Beverages, A/C Units, Slackers, Squatters, Hipsters, and Urban Loft-Dwellers

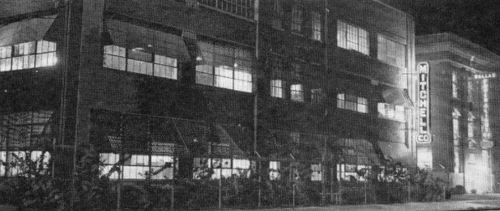

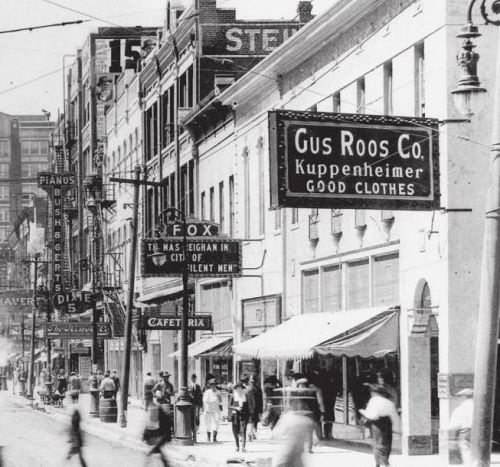

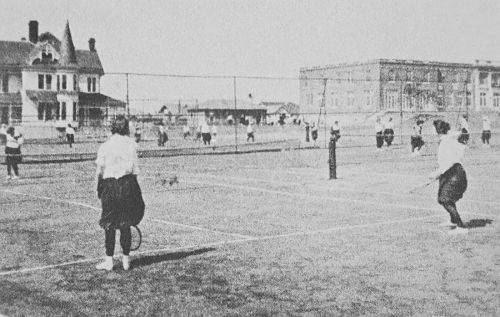

In 1988, the building had seen better days… (click for larger image)

In 1988, the building had seen better days… (click for larger image)

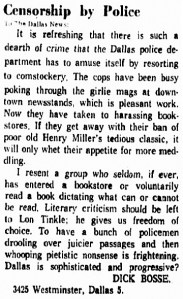

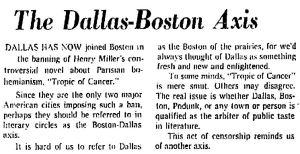

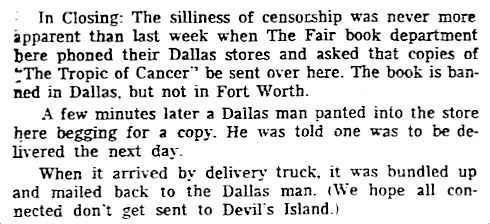

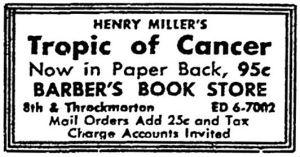

by Paula Bosse

In 1928, the John E. Mitchell Company (discussed previously here, here, and here) arrived in Dallas from St. Louis and built their J. A. Pitzinger-designed 2-story factory at 3800 Commerce Street (a wing was added the next year, and a third story was added the year after that). It produced cotton gins and farm implements. As strange as it seems today, Dallas was once the largest producer of cotton gin machinery in the United States. The Mitchell Company was located in a mostly industrial area very close to several other cotton gin manufacturers (such as the nearby Continental Gin Company and Murray Company). At the height of their production, these Dallas factories were responsible for half of the world’s cotton gins.

When World War II hit, the company became an important defense contractor and produced munitions for the U.S. Navy and U.S. Army, making things such as “anti-submarine projectiles,” anti-aircraft shells, rocket nozzles, and “adapters for incendiary bomb clusters.”

After the war, the Mitchell Company continued to manufacture agricultural implements but diversified by turning out other types of machinery, like automobile air conditioners and and cleaning systems. As the 1960s dawned, they developed the machine that made ICEE frozen slushy drinks (forever immortalized by 7-Eleven as The Slurpee).

After the death of company president John E. Mitchell, Jr. in 1972, the business began a slow slide downward. The company appears to have gone out of business in the early 1980s. In the fall of 1982, the company’s equipment was sold at public auction, and, in 1984, the building became the temporary home of the Junior Black Academy of Arts and Letters.

In the 1980s, Deep Ellum and Exposition Park began to explode with new bars, clubs, and galleries. If it was cool, it was in Deep Ellum and Expo Park; if it was in Deep Ellum and Expo Park, it was cool. Artists and musicians began to move into many of the neighborhood’s old warehouses. These usually run-down buildings — in which bohemian types lived (not always legally) and used as studio spaces — were huge and (in the beginning) cheap. The Mitchell Building became something of a ground zero for wild parties and was described in a fantastic 1995 newspaper article by Shermakaye Bass (linked below) as both a “flophouse” and “an artists commune and downtown slacker den.” The building was closed and boarded up by its owners in early 1995 in order to avoid code-violation citations, but by 1999 the building had been purchased, cleaned up, modernized, and converted into 79 loft apartments. Today, the Mitchell Lofts have been a part of the Expo Park scene for almost 20 years.

*

In 1991, the Mitchell Building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The photographs below (and the one at the top) were included in the application form. They were taken by Daniel Hardy of Hardy-Heck-Moore in October, 1988. Things weren’t looking great for the building in 1988. It must have been quite an undertaking to convert this large L-shaped building (which had certainly seen better days) into hip, sleek lofts.

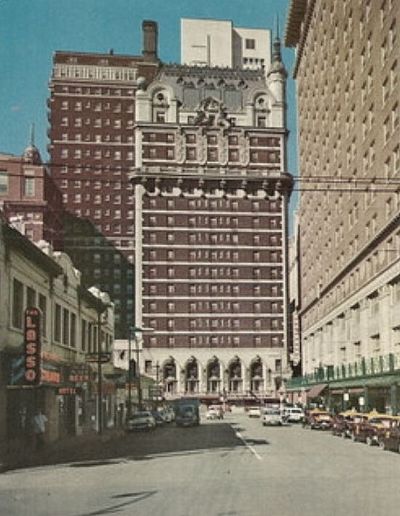

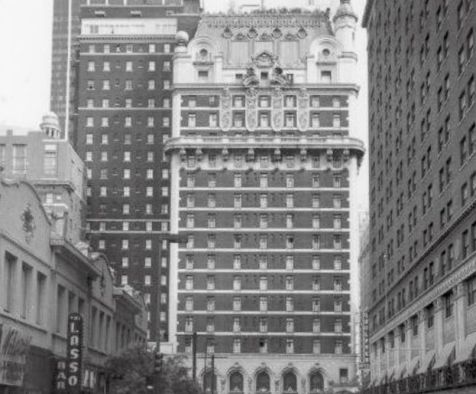

Below, looking northwest on Commerce. The Mitchell Building is in an L-shape — the smaller building in the foreground is an old Dallas Power and Light substation, built around 1925. (Click photos to see larger images.)

*

The back, from the old T&P/Missouri-Pacific railroad tracks.

*

And two interior views of the second floor.

*

Here’s what the exterior looks like today, spiffified. (Explore it on Google Street view here.)

Google Street View (Jan. 2016)

Google Street View (Jan. 2016)

**

Mitchell War Book, ca. 1945

***

Sources & Notes

Photos are from the application to the National Register of Historic Places; in addition to the photos, there is a thorough history of both the building and the John E. Mitchell Company, written by David Moore of Hardy-Heck-Moore. The 28-page form can be found in a PDF, here. (3/14/17 UPDATE: The link no longer works for me, and I am unable to find the document. Here’s the full URL: ftp://ftp.dallascityhall.com/Historic/National%20Register/John_E_Mitchell_Plant.pdf.)

More info on the Mitchell Company and its building through the years can be found in the following Dallas Morning News articles:

- “Dallas Gets Gin Factory” (DMN, March 17, 1928) — the announcement that a permit has been granted for the construction of a two-story brick factory and warehouse

- “John E. Mitchell Exemplifies Faith as Secret to Success,” by Helen Bullock (DMN, July 17, 1949) — an entertaining profile of John E. Mitchell, Jr.

- “Demise of a Dream Factory — Deep Ellum’s Historic Mitchell Building Leaves a Legacy of Artistic and Industrial Vision,” by Shermakaye Bass (DMN, Feb. 5, 1995) — for those who grew up when Deep Ellum was experiencing its (first) renaissance, the article is a great snapshot of what things were like in Deep Ellum and Exposition Park back in the ’80s and early ’90s

See what the Mitchell Lofts look like now in this Candy’s Dirt article from 2014; more photos are here. Pretty hard to believe people used to manufacture things like cotton gins and anti-aircraft missiles there.

The Mitchell Lofts website is here.

Click pictures and clipping to see larger images.

*

Copyright © 2016 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.