“Dallas — The City That Decided Not To Die of Thirst”

“Dallas — The City That Decided Not To Die of Thirst”

by Paula Bosse

Between 1950 and 1957, Texas suffered the worst drought on record. By 1957, 244 of Texas’ 254 counties had been declared disaster areas. In 1952, Lubbock recorded not even a trace of rain. Elmer Kelton captured the period perfectly in his classic novel, The Time It Never Rained. It might not have achieved the epic catastrophic proportions of the Dust Bowl days, but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t devastating.

In Dallas, the lakes and reservoirs were hit hard. White Rock Lake dried up — one was able to walk across the parched lake bed without a drop of water in sight. Lake Dallas (now Lake Lewisville) fell to 11% of capacity. Dallas was desperate for water, and in 1956, it began “importing” water from Oklahoma. Red River water was appreciated, but it was considered by many far too salty to drink. In addition to the unpleasant taste, residents were concerned that there would be permanent damage to pipes and plumbing, and, to a lesser extent (since watering restrictions were being strictly enforced) to their lawns.

According to one report, salt content in the water supply had gone from the normal 39 parts per million gallons to over 800 parts (at the height of the problem, some news outlets reported it to be well over 2,000 parts per million). While the water was generally considered perfectly safe for the average person to drink, many looked for cleaner, more palatable drinking water.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Aug. 23, 1956 (click for larger image)

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Aug. 23, 1956 (click for larger image)

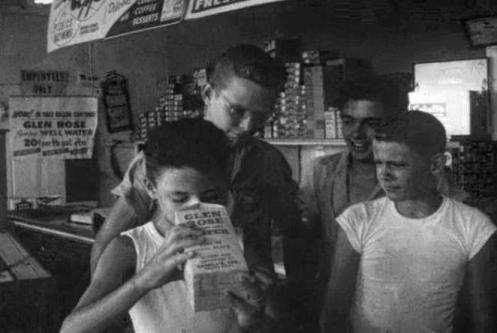

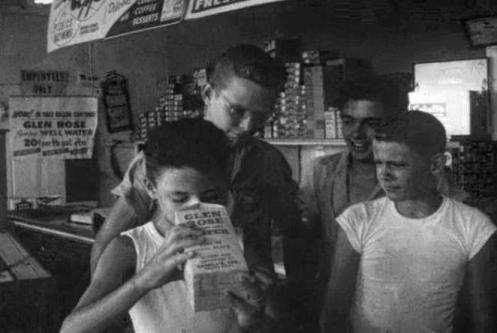

Suddenly bottled water became a boom business. Spring water was being trucked to Dallas from Glen Rose and Arkansas. Water was being sold in bottles and cartons — from 20 cents per half-gallon cartons to $2.50 for five-gallon bottles ($1.50 of which was for a deposit on the glass bottle). WBAP-TV news even sent a cameraman out to a Cabell’s convenience store to capture some boys testing out the Glen Rose water (watch it here, without sound).

The other source of acceptable drinking water that summer was from city wells dotted around Dallas. Long dormant, the city opened the wells and offered free water to residents. From The Dallas Morning News:

If you don’t like that hard, salty water coming from your taps, you can get soft, unsalty water at four city wells beginning Sunday. City manager Elgin E. Crull Saturday said that the city has installed faucets at the four wells where people may take their buckets or bottles and obtain drinking water. No trucks will be permitted to fill up. (DMN, Aug. 19, 1956)

The four wells mentioned above — and two more opened within a few weeks — were located at the following locations:

- 1325 Holcomb, near Lake June Road

- Opera and 13th, near the Marsalis Zoo

- 875 North Hampton, near Lauraette Street

- 2825 Bethurum, in South Dallas, near the public housing project

- Northwest Highway and Buckner

- Matilda and Anita, on the grounds of Stonewall Jackson Elementary School, in East Dallas

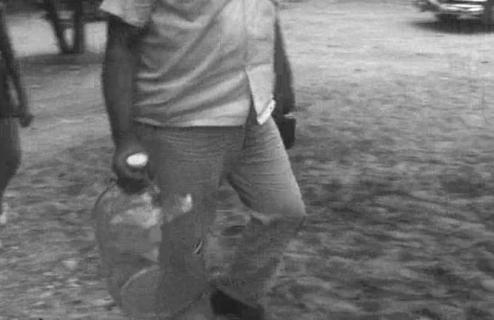

These wells were hugely popular, with thousands of people showing up with jugs, jars, kettles, canteens, and bottles of every conceivable size. (More WBAP news footage of people filling up at these wells can be seen here, without sound; details below).

The popularity of the city wells led to private citizens having wells dug on their own property. Not only were bottled water suppliers making a killing during the summer of ’56, so were the owners of drilling businesses. From The Dallas Morning News:

As salty water from city mains reportedly discourages shrubbery and affronts the taste, drillers of shallow residential water wells ride the crest of a boom. […] Luckiest of the water-seekers are residents of the southern section of the city in the Fruitdale, Pleasant Grove and Home Gardens area, and in the neighborhoods that border Loop 12. That is where drillers are finding pay dirt — water-bearing gravel — at shallow depths. (DMN, Oct. 7, 1956)

It wasn’t just professional drillers who were busy — it wasn’t uncommon for the DIY-ers to be out in the backyard on weekends, digging away, hoping for their own personal source of fresh water. And there were probably even some dowsers out and about, water witching their little hearts out.

The drought ended the next year, and personal wells were a thing of the past, but that mania for bottled water really dug its heels in.

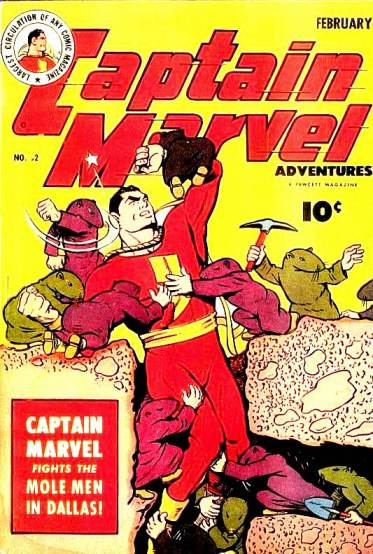

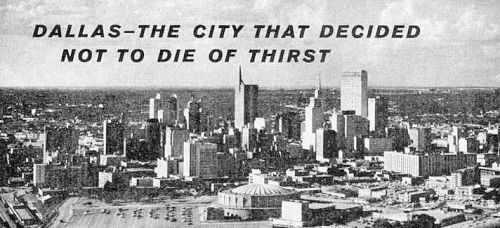

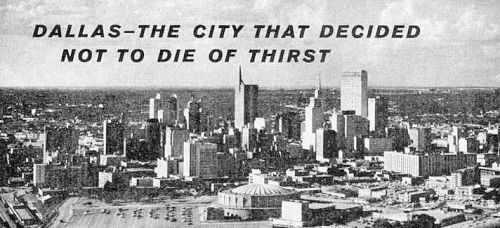

Texas developed the Water Planning Act of 1957, and in 1962, this new mandate and what had happened in Dallas during the drought was used as the basis for a Caterpillar ad which had a bit of a hyperbolic headline, “Dallas — The City That Decided Not To Die Of Thirst”:

1962 ad (click for larger image)

1962 ad (click for larger image)

***

Sources & Notes

Picture of the four boys tasting the Glen Rose water is taken from the WBAP-TV news story that aired on Aug. 12, 1956. The silent, edited footage was shown as the news anchor read the script, seen here. Film footage (linked above) and script from the Portal to Texas History.

The two pictures of people availing themselves of water from the city’s wells are taken from the WBAP-TV news story that aired on Aug. 19, 1956. The silent footage ran as the anchor read the script seen here and here. Film footage (linked above) and script from the Portal to Texas History.

1962 Caterpillar ad from eBay.

More on affect of the drought on Dallas can be found in these Dallas Morning News articles:

- “Sparked by Salt: Business Booming For Bottled Water” (DMN, Aug. 5, 1956)

- “Citizens Stock Up On Saltless Water” by Sue Connally (DMN, Aug. 20, 1956)

- “Thirsty City Witnesses Revival of Well Drilling” by William K. Stuckey (DMN, Oct. 7, 1956)

- “Resourceful Citizens Tap City Water Well” (DMN, Oct. 16, 1956)

- “Continuing Drouth Produces Top Local News Story in ’56” by Patsy Jo Faught (DMN, Dec. 30, 1956)

Read about how the drought affected Texas water management here; read about the Texas Water Rights Commission here.

Read “The City of Dallas Water Utilities Drought Management Update” in a PDF, here.

Finally, I encourage everyone to grab a tall glass of ice water and settle down to read Elmer Kelton’s classic Texas novel, The Time It Never Rained. Or if you’re pressed for time, read Mike Cox’s article about the book in Texas Parks & Wildlife magazine, here.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

June 28, 1967

June 28, 1967

“Dallas — The City That Decided Not To Die of Thirst”

“Dallas — The City That Decided Not To Die of Thirst”