Ferris Plaza Waiting Station — 1925-1950

From The Electric Railway Journal, 1926

From The Electric Railway Journal, 1926

by Paula Bosse

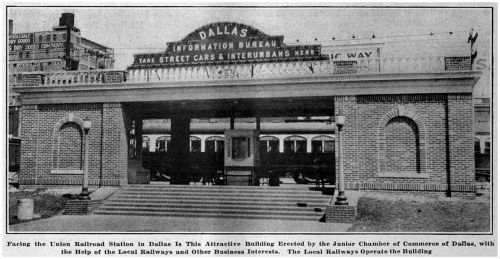

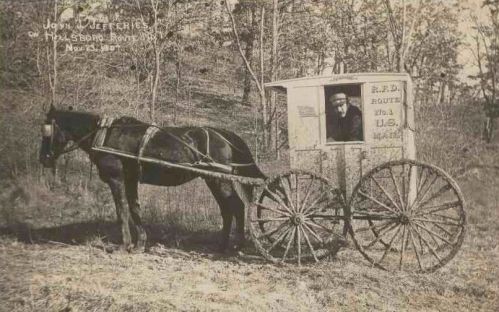

I came across the odd image above whilst digitally thumbing through a 1926 issue of The Electric Railway Journal (as one does…) and wondered what it was. It was definitely something I’d never seen downtown. Turns out it was a combination information bureau, covered stop in which to buy tickets for and await the arrival of interurbans and streetcars, a place to purchase a snack, and a location of public toilets (or, more euphemistically, “comfort stations”). It was located at the eastern edge of Ferris Park along Jefferson Street (which is now Record Street), with the view above facing Union Station. It was intended to be a helpful, welcoming place where visitors who had just arrived by train could obtain information about the city, and it was also a pleasant place to wait for the mass transit cars to spirit them away to points beyond. With the lovely Ferris Plaza (designed by George Dahl in 1925) between it and the front of the Union Terminal, this was considered The Gateway to the City long before Dealey’s Triple Underpass was constructed. (Click photos and articles to see larger images.)

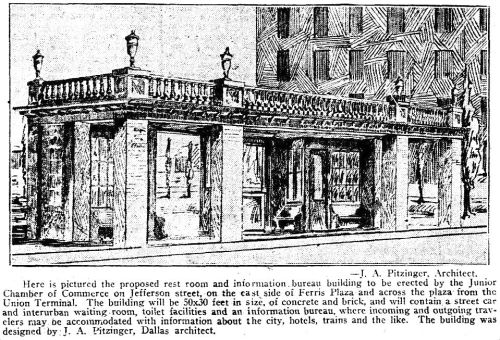

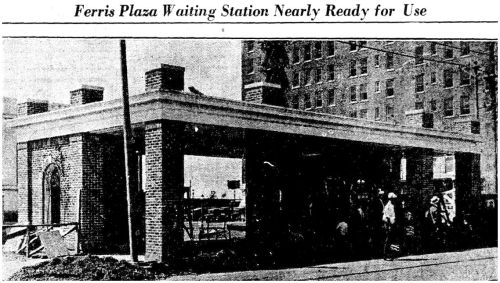

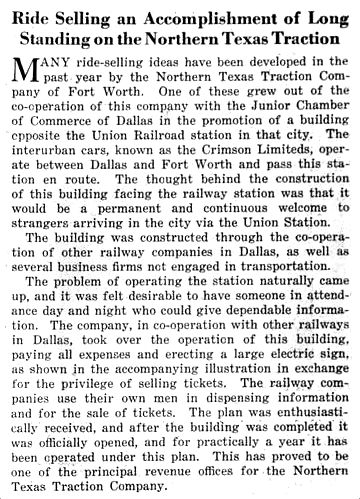

The “waiting station” was the brainchild of the Dallas Junior Chamber of Commerce which proposed the idea to the City of Dallas and, as it was to be built at the edge of a city park, the Park Board. The small (50 x 30) brick building — designed by Dallas architect J. A. Pitzinger — would cost $5,000 and would be paid for by funding from local businesses, including various transportation concerns (namely, the Northern Texas Traction Company). The “traction” companies would staff the information booth and sell tickets. The plans were accepted and permission was granted. Construction began in July, 1925, and the building was opened for waiting by October.

This improvement is the most recent of a number which have made of Ferris Plaza a beauty spot at the gateway of the city. Designed for a sunken garden, fringed with trees, the plaza is now adorned with a great fountain, illuminated with colored lighting at night, the gift of Royal A. Ferris. The new waiting station is in harmony with the general scheme of the plaza development, and combines beauty with utility. (Dallas Morning News, Sept. 20, 1925)

The little waiting station proved to be quite popular, and by the end of its first year the Northern Texas Traction Company (who operated interurban service between Dallas and Fort Worth) was very pleased, as interurban ticket sales at the station had become a solid source of company revenue. The Ferris Plaza station lasted a rather surprising 25 years. It was torn down in 1950, mainly because the interurbans had been taken out of service and there was no longer a need for it. Also, the park department was eager to get their park back and make it more “symmetrical.”

People would just have to wait somewhere else.

*

Architectural rendering by J. A. Pitzinger (DMN, March 16, 1925)

Architectural rendering by J. A. Pitzinger (DMN, March 16, 1925)

Nearing completion (DMN, Sept. 20, 1925)

Nearing completion (DMN, Sept. 20, 1925)

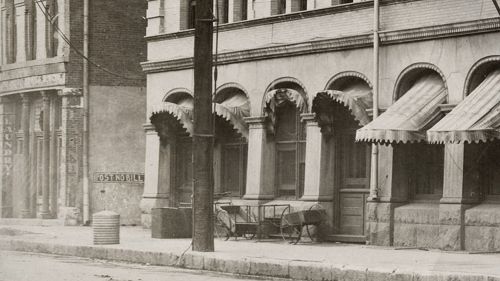

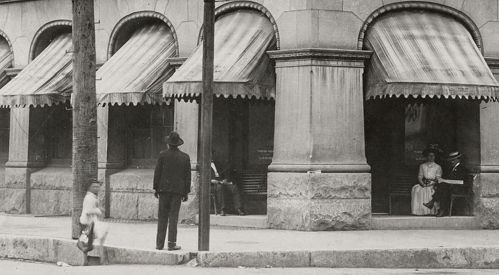

DeGolyer Library, SMU (cropped)

DeGolyer Library, SMU (cropped)

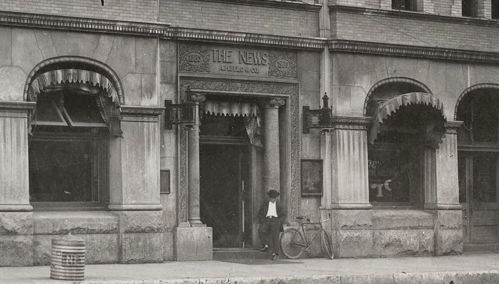

The Electric Railway Journal (Nov. 6, 1926)

The Electric Railway Journal (Nov. 6, 1926)

Union Station, 1936 — view from the “waiting station” (Dallas Public Library)

Union Station, 1936 — view from the “waiting station” (Dallas Public Library)

1949 aerial view, showing “waiting station” just above plaza’s circular fountain

1949 aerial view, showing “waiting station” just above plaza’s circular fountain

***

Sources & Notes

Top photo from The Electric Railway Journal, Nov. 6, 1926.

Very early photo and description of Ferris Plaza is from Park and Playground System: Report of the Park Board of the City of Dallas, 1921-1923, via the Portal to Texas History, here.

Cropped image showing the waiting station with the Jefferson Hotel in the background is from the DeGolyer Library, SMU — more info is here.

Photograph of Union Station from the Texas/Dallas History and Archives Division of the Dallas Public Library.

Aerial photo showing Ferris Plaza is from a larger view of downtown by Lloyd M. Long (the original of which is in the Edwin J. Foscue Map Library collection of the Central University Libraries, Southern Methodist University, and which can be viewed here).

To read about the Ferris Park restoration project, see here.

For a few interesting and weird tidbits about the block that eventually became Ferris Plaza (including the fact that it was thought to be haunted and that it was once the site of a brothel), check out this page on Jim Wheat’s fantastic site.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

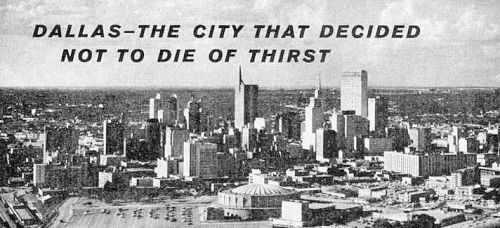

“Dallas — The City That Decided Not To Die of Thirst”

“Dallas — The City That Decided Not To Die of Thirst”

DMN, July 17, 1921

DMN, July 17, 1921 DMN, Nov. 4, 1923

DMN, Nov. 4, 1923

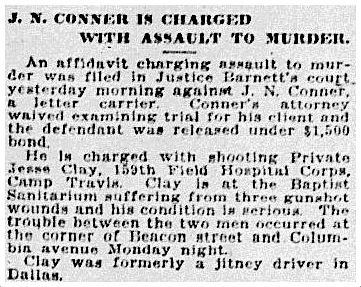

Fort Worth Register, Sept. 1, 1901

Fort Worth Register, Sept. 1, 1901 DMN, Jan. 2, 1918

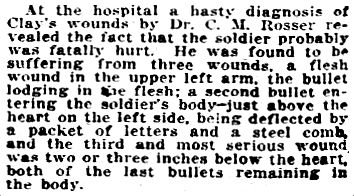

DMN, Jan. 2, 1918 DMN, Jan. 1, 1918

DMN, Jan. 1, 1918

DMN, Jan. 8, 1890

DMN, Jan. 8, 1890 DMN, Jan. 8, 1890

DMN, Jan. 8, 1890 DMN, Feb. 6, 1890

DMN, Feb. 6, 1890 DMN, Oct. 10, 1990

DMN, Oct. 10, 1990 DMN, Oct. 11, 1890

DMN, Oct. 11, 1890

Greenwood Cemetery, Dallas (photo: David N. Lotz)

Greenwood Cemetery, Dallas (photo: David N. Lotz)