How Lincoln’s Assassination Was Reported in Dallas — 1865

by Paula Bosse

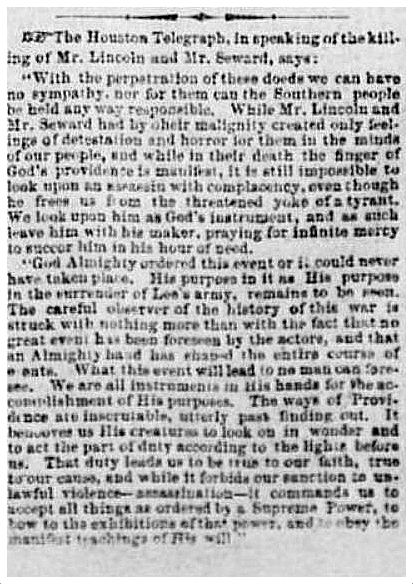

Abraham Lincoln was shot by John Wilkes Booth on April 14, 1865; he died the next morning. I wondered how the news had been reported in Dallas. I couldn’t find the first mention of the assassination in The Dallas Herald, but it seems there may have been a special “extra” edition published on or just after April 29th — a full two weeks after the fact! The one thing I kept encountering in general Google searches were mentions of the vicious, celebratory editorial that appeared in the pages of the Herald — these reports always quote the line “God Almighty ordered this event or it could never have taken place.” I found that editorial. It appeared in the two-page Dallas Herald on May 4, 1865, along with detailed reports of the assassination.

The image resolution here is pretty bad (it is transcribed below), but, yes, this eye-poppingly vitriolic editorial did appear in the pages of The Dallas Herald — but it did not originate with the Herald (which is not to say that the Dallas editor wasn’t in agreement with the sentiments expressed). The editorial was reprinted from the Houston Tri-Weekly Telegraph (which had run it ten days previously, on April 24); its appearance in the Dallas paper is even clearly prefaced with the following: “The Houston Telegraph, in speaking of the killing of Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Seward, says…” — so it’s unclear why so many historians and authors mention this editorial as being the product of The Dallas Herald.

The editorial was unsigned, but it was probably written by William Pitt Ballinger, whose previous flame-fanning tirades against the president in the pages of the Telegraph must have caused even hard-core Confederate-leaning brows to raise. I’ve transcribed the full editorial below. For whatever reasons, the Dallas Herald omitted the first and last paragraphs — probably because of space limitations, but one would like to think that even a pro-Confederacy newspaper would think it best to leave out a phrase such as “The killing of Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Seward may be more wonderful than the capitulation of armies.” Yikes. Imagine a mainstream newspaper printing something like that following the assassination of President Kennedy.

Below is the full astonishing text of the editorial that originally appeared in the Houston Tri-Weekly Telegraph on April 24, 1865. The stark reality of historical events and the contemporaneous tenor of the times can look a lot different when seen from a distance of 150 years.

*

We publish to-day the most astounding intelligence it has ever been our lot to place before our readers — intelligence of events which may decide the fate of empires, and change the complexion of an age. The killing of Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Seward may be more wonderful than the capitulation of armies.

With the perpetration of these deeds we can have no sympathy, nor for them can the Southern people be held any way responsible. While Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Seward had by their malignity created only feelings of detestation and horror for them in the minds of our people, and while in their death the finger of God’s providence is manifest, it is still impossible to look upon an assassin with complacency, even though he frees us from the threatened yoke of a tyrant. We look upon his as God’s instrument, and as such leave him with his maker, praying for infinite mercy to succor him in his hour of need.

God Almighty ordered this event or it could never have taken place. His purpose in it as His purpose in the surrender of Lee’s army, remains to be seen. The careful observer of the history of this war is struck with nothing more than with the fact that no great event has been foreseen by the actors, and that an Almighty hand has shaped the entire course of events. What this event will lead to no man can foresee. We are all instruments in His hands for the accomplishment of His purposes. The ways of Providence are inscrutable, utterly past finding out. It behooves us His creatures to look on in wonder and to act the part of duty according to the lights before us. That duty leads us to be true to our faith, true to our cause, and while it forbids our sanction to unlawful violence — to assassination — it commands us to accept all things as ordered by a Supreme Power, to bow to the exhibitions of that power, and to obey the manifest teachings of His will.

What will [be] the result of these tremendous events, no man can foresee. Theories will present themselves to every man’s mind. We have a dozen all equally probable, and all equally uncertain. Let us wait in patience for the next scene in this terrible drama.

***

Top image is an engraving of the assassination in Ford’s Theatre from Harper’s Weekly, April 29, 1865.

Editorial is from The Houston Tri-Weekly Telegraph, published April 24, 1865 (Vol. 31, No. 13). You can view a scan of the original newspaper via the indispensable Portal to Texas History, here (it is at the top right of the page, last column). Reprinted without the first and last paragraph by The Dallas Herald ten days later on May 4, 1865 (Vol. 12, No. 36).

Editorial is probably by William Pitt Ballinger, a Galveston attorney. His editorial screeds for the Telegraph are mentioned in the just-published Loathing Lincoln: An American Tradition from the Civil War to the Present, by John McKee Barr (LSU Press, 2014), p. 53 — read an excerpt here. Read more about Ballinger — the “brilliant attorney and political insider” — here.

An interesting article titled “The Last Newspaper to Report the Lincoln Assassination” is here. The article is about The Houston Tri-Weekly Telegraph, but it looks like The Dallas Herald was even SLOWER to report the news.

“We received on Saturday last [April 29] the dispatches containing the assassination of Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Seward, by a letter from Maj. Stackpole to his family at this place, and published them in an extra. There was some little discrtepancy and an omission in them as published then, which we find corrected in the Houston Telegraph’s dispatches which we publish to-day.” (Dallas Herald, May 5, 1865)

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

Photo by Silver Lighthouse/Flickr

Photo by Silver Lighthouse/Flickr

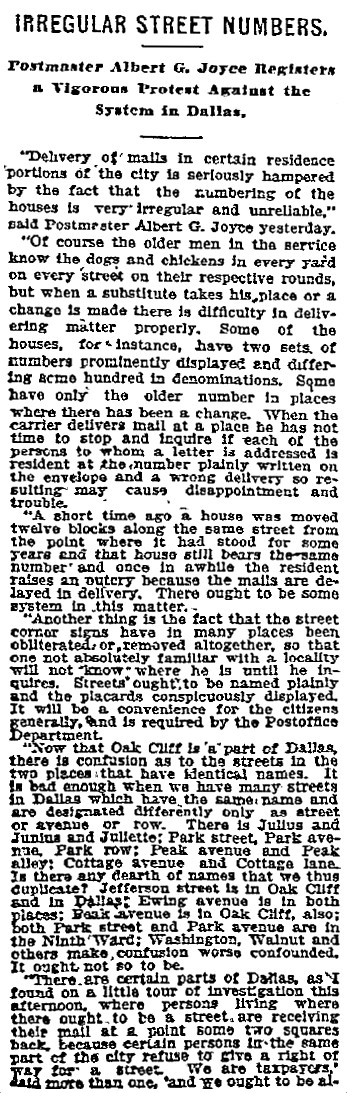

(DMN, Dec. 7, 1907)

(DMN, Dec. 7, 1907) (DMN, Dec. 17, 1909)

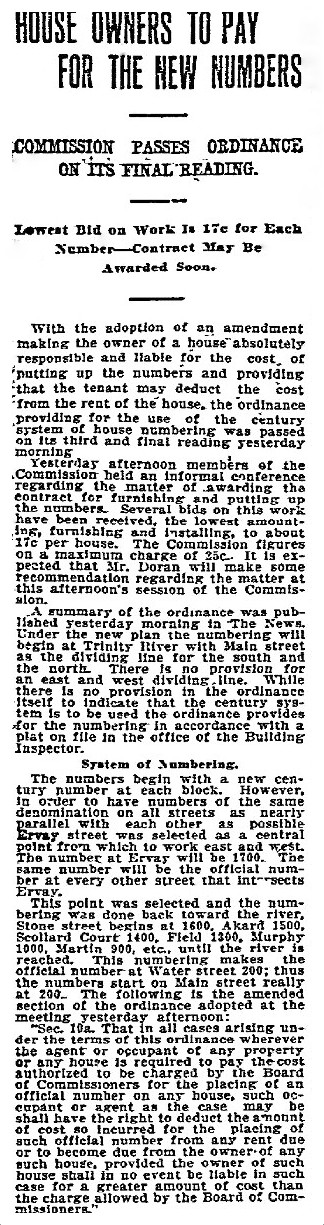

(DMN, Dec. 17, 1909) (DMN, Oct. 1, 1910)

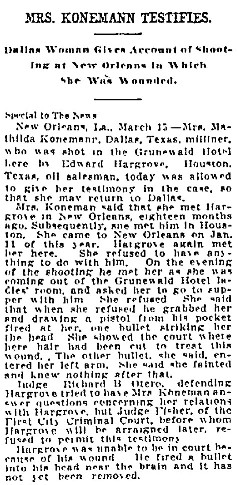

(DMN, Oct. 1, 1910) (DMN, Jan. 15, 1911)

(DMN, Jan. 15, 1911) (DMN, Apr., 30, 1911)

(DMN, Apr., 30, 1911)

(Texas Dept. of Transportation, 2003)

(Texas Dept. of Transportation, 2003)

(Southern-Mercury, Dec. 31, 1903)

(Southern-Mercury, Dec. 31, 1903)

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 21, 1913

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 21, 1913 Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Feb. 17, 1917

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Feb. 17, 1917

DMN, June 15, 1922

DMN, June 15, 1922

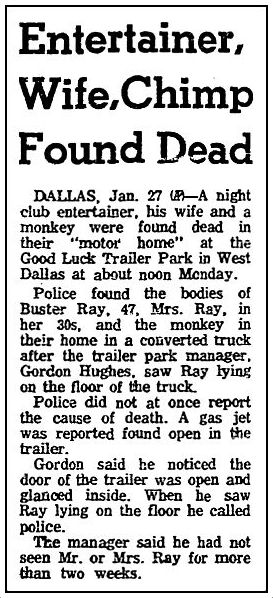

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Jan. 28, 1964

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Jan. 28, 1964 Corpus Christi Caller-Times, April 29, 1948

Corpus Christi Caller-Times, April 29, 1948