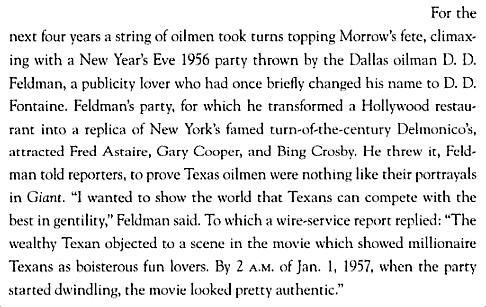

Orson at 18 — publicity photo used for the Cornell tour, 1934

by Paula Bosse

Today is the 100th anniversary of the birth of Orson Welles. Welles was one of the truly great, innovative theater and film directors, an actor with a commanding presence, and a delightfully entertaining raconteur. His frenetically creative work on the New York stage, on radio, and in film (he wrote, produced, directed, and acted in his first film, Citizen Kane, when he was only 25) earned him/saddled him with the hard-to-deny sobriquet “Boy Genius.” His rise up the show-biz ladder was a quick one.

Orson’s first professional acting gig was as an unknown 18-year old repertory player in the touring company of famed actress Katharine Cornell who, along with British actor Basil Rathbone, starred in the three plays performed on the tour, which stopped in Dallas for a two-night engagement at the Melba theater, in February, 1934. The three plays performed in Dallas on February 19 and 20 (one a matinee) were “Romeo and Juliet” (Orson played Mercutio), “The Barretts of Wimpole Street” (he played Octavius Moulton-Barrett), and “Candida” (he played Marchbanks). Cornell was a huge draw, and there was a rush for tickets. The Melba begged her to extend her stay and add performances, but she declined.

The young Welles had gotten reviews on the tour which ranged from a dismissive mention in Variety that he was unable to speak Shakespeare’s lines properly and audibly (!), to raves from Charles Collins of The Chicago Tribune:

The cast is brilliant, and many of the secondary characters are acted with consummate skill. This is particularly true of Orson Welles’ Mercutio, which is an astonishing achievement for a youth still new on the stage. In his duel with Tybalt and his death scene, this Mercutio is a complete realization of Shakespeare’s bravest blade.

The star of the show was the then-very-famous Katharine Cornell, around whom most of the articles and reviews centered (she was, for instance, breathlessly reported to be staying at the Melrose during her Dallas stay) (I wonder if the lowly company players — i.e. Orson Welles — stayed there as well?). The Dallas Morning News theater critic, John Rosenfield — who mentioned this 1934 Dallas appearance in almost every succeeding article he ever wrote about Orson Welles over the next several decades — wrote the following before he saw Orson’s performances in any of the three plays:

Orson Welles, 18-year-old actor, who is apparently bulky enough to hold his own with adults, will be Mercutio. (DMN, Feb. 19, 1934)

After he saw his Mercutio:

Orson Welles’ Mercutio was up to the best standards known for this role. (DMN, Feb. 20, 1934)

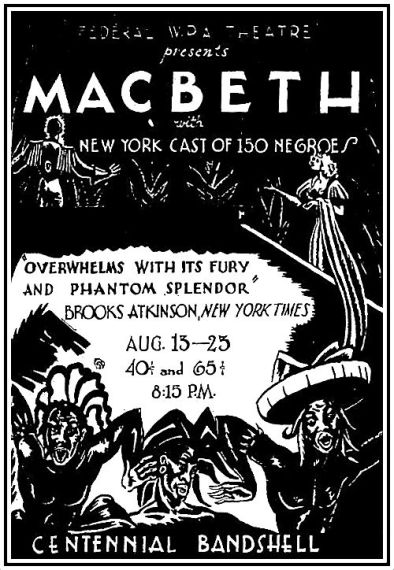

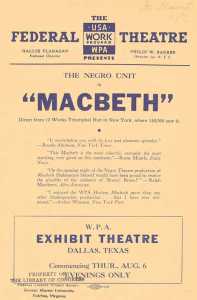

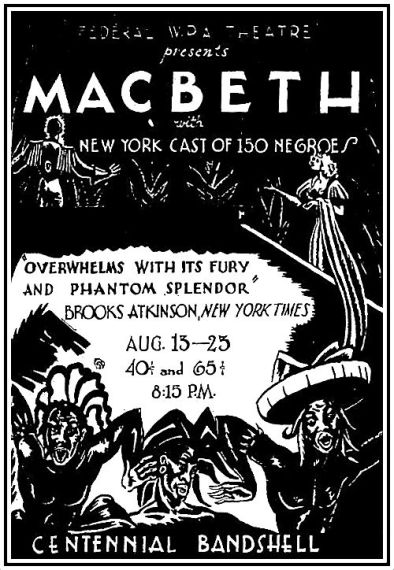

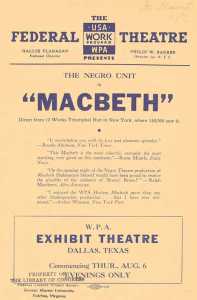

When the tour finished, Welles quickly became a presence in the New York theater world. One of his early successes as a producer and director was his production of the so-called “Black Macbeth”/”Negro Macbeth”/”Voodoo Macbeth” — a hugely popular staging of Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” with an all-black cast, done under the auspices of the Federal Theatre Project in 1936. In August of that year — just two and a half years after his appearance as an unknown at the Melba — he took the production to Dallas where it made a splash at the Texas Centennial in the brand new bandshell.

Aug., 1936

Aug., 1936

(click for larger image)

(click for larger image)

Rosenfield was impressed by the lush design and the electric and inventive spectacle, but he was not a fan of the performances. A few years later, on the eve of the release of Citizen Kane, he wrote the following (which was much harsher than his original 1936 review):

We saw this production in Dallas during the Texas Centennial and could marvel at the artistic futility of such ingenuity. The Negro Macbeth, however, was something to be seen if only to be despised. (DMN, Oct. 29, 1941)

Oh dear.

In 1940, Welles was working on his first film, the legendary Citizen Kane. As filming began to wind down, he decided to go out on a short lecture tour because he was in desperate need of money (an all-too-common circumstance he found himself in throughout the entirety of his career). His topic was a vague “anecdotes of the stage and theories on the drama” — and it sounds like his “performances” were largely unscripted and unrehearsed.

On October 29, 1940 — only a week or two after wrapping production on Citizen Kane — 25-year old Orson Welles spoke at McFarlin Auditorium on the SMU campus as part of the Community Course series of lectures. His topic: The Actor’s Place in the Theater. It was another packed house of adoring and/or curious Dallasites. Rosenfield was both entertained and annoyed by the rambling “lecture,” but Orson was undoubtedly delighted to talk for two hours before an adoring crowd, answer their questions about his craft, and collect a $1,200 check.

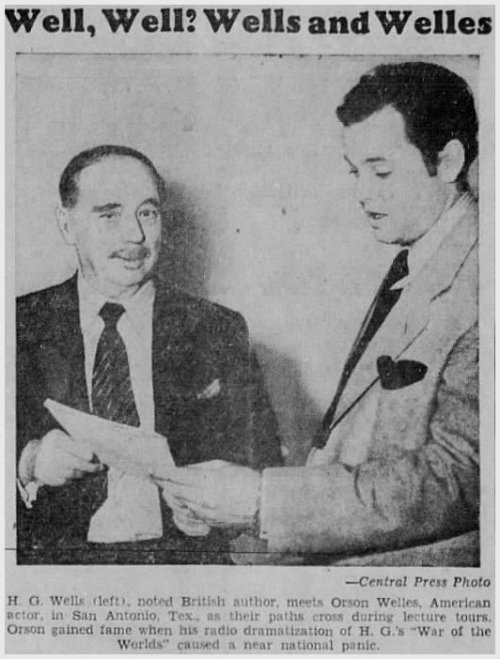

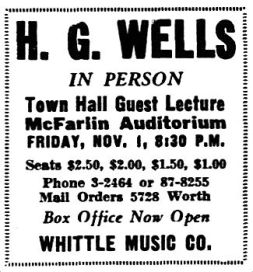

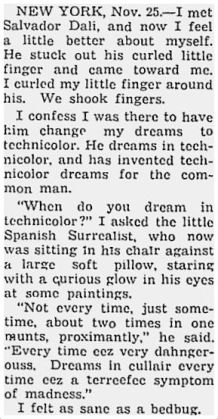

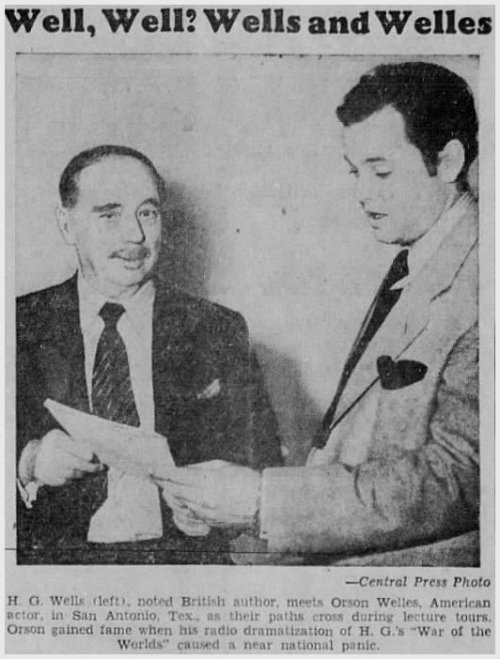

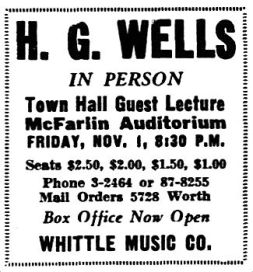

Orson’s appearance in Dallas was particularly noteworthy for the fact that the speaker scheduled to appear on the McFarlin stage just three days later was … H. G. Wells! At the time of this lecture tour, Orson was best known for his infamous 1938 radio adaption of H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, the frighteningly realistic production that panicked the nation and led thousands to believe that the earth was being attacked by Martians. Rather surprisingly, Welles and Wells had never met.

According to a blurb in a Phoenix newspaper, Orson had cancelled a previously-scheduled meeting in Tucson in order to fly into Dallas earlier than planned. My guess is that he saw that H. G. Wells was also lecturing in Texas and realized that H. G.’s lecture in San Antonio the night before Orson’s own appearance in Dallas on the 29th was the only chance he had to meet the man who had provided the source-material for his (to-date) greatest career triumph.

A quick timeline:

- Sun. Oct. 27, 1940: Orson arrives in Dallas, staying at the Baker Hotel.

- Mon. Oct. 28: In the morning, Orson flies down to San Antonio to meet H. G. Wells and attend his lecture. The two meet, get along famously, have their photos taken, and give a short joint interview to San Antonio radio station KTSA (see below for link to recording). That evening, both fly to Dallas. Later that night, Orson (well known as an amateur magician) pops into The Mural Room in the Baker Hotel to catch the floor show featuring popular magician Russell Swann.

- Tues. Oct. 29: H. G. Wells leaves Dallas for Denver, continuing his lecture tour. That morning Orson drives to Fort Worth to present a lecture and attend a luncheon at the River Crest Country Club. That night, he presents his lecture at McFarlin Auditorium at Southern Methodist University. After his lecture, he catches Russell Swann’s magic show for a second time. At 3:00 a.m. he flies to San Antonio for his lecture there.

- Wed. Oct. 30: Orson lectures in San Antonio. It is the second anniversary of the broadcast of “The War of the Worlds.” Conveniently, newspapers around the country begin to run the photos of Welles and Wells taken on the 28th.

- Thurs. Oct. 31: A Martian-free Halloween.

- Fri. Nov. 1: H. G. Wells is back in Dallas for his lecture that night at McFarlin Auditorium.

Pottsdown (PA) Mercury, Oct. 31, 1940

Pottsdown (PA) Mercury, Oct. 31, 1940

DMN, Oct. 29, 1940

DMN, Oct. 29, 1940

Whew.

Happy 100th, Orson! And thanks for everything.

***

Sources & Notes

Dates and sources of newspaper clippings as noted.

“Macbeth” playbill from the Library of Congress, here.

The timeline for the Welles-Wells meeting and their Dallas-related activities were gleaned from a report in the Oct. 30, 1940 edition of The Dallas Morning News.

And now, links galore.

- Watch an entertaining short clip in which Orson talks about mind-reading and fortune-telling — which he says he indulged in on the Cornell tour — here.

- Read the profile of the 18-year-old phenom which appeared in newspapers during the run of the Katharine Cornell tour, here.

- Read about the “Voodoo Macbeth” here (scroll to the bottom to see fantastic photos).

- Listen to the interview with Orson Welles and H. G. Wells that aired on San Antonio station KTSA, the day they met for the first time, on Oct. 28, 1940 — here.

- Read about that still-chilling Mercury Theatre radio broadcast of The War of the Worlds, here.

Finally, my favorite Orson Welles-related quote from the erudite and not-without-humor arts critic of The Dallas Morning News, John Rosenfield. He wrote the following in his review of the set-in-Haiti “Macbeth” — about the aesthetic viability of future Shakespeare productions tailored for specific audiences:

…Mr. Welles hasn’t started a movement. His Negro “Macbeth” does not inspire us to corroborate a fabled Texas lawyer and make Antonio “The Merchant of Ennis.” (DMN, Aug. 16, 1936)

“THE MERCHANT OF ENNIS”! Someone! Make this happen!

*

Copyright © 2015 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

New York Post, Nov. 26, 1944

New York Post, Nov. 26, 1944

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Sept. 26, 1972

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Sept. 26, 1972

Josey Rancho

Josey Rancho

Oct. 1954 (©Bettmann/CORBIS)

Oct. 1954 (©Bettmann/CORBIS)