Santos Rodriguez, 1960-1973

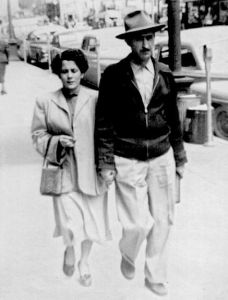

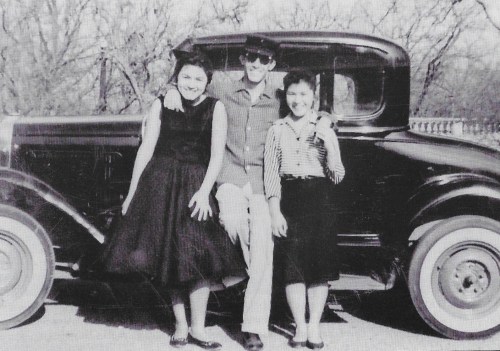

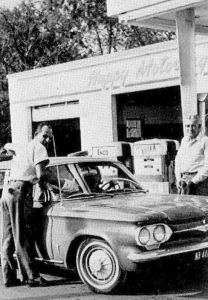

David and Santos Rodriguez (via Austin American-Statesman)

David and Santos Rodriguez (via Austin American-Statesman)

by Paula Bosse

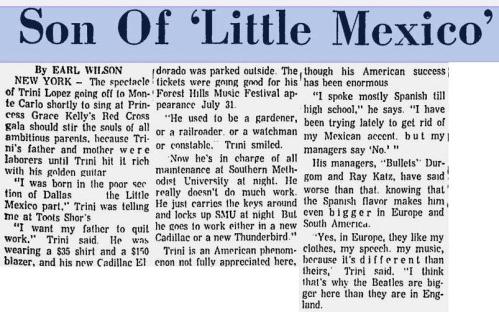

Today is the anniversary of the tragic shooting of Santos Rodriguez, the 12-year-old boy who, on July 24, 1973, was shot in the head by a policeman as he and his 13-year-old brother David sat handcuffed in a police car. It shocked the city of Dallas in 1973, and it is still shocking today.

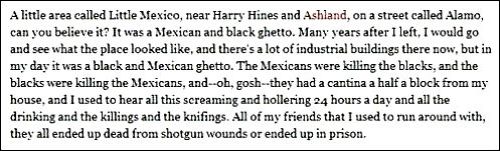

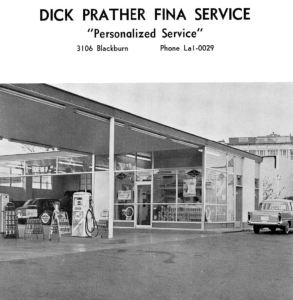

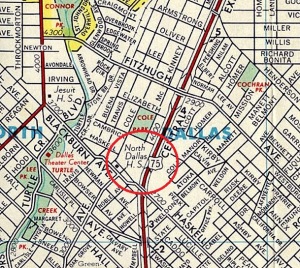

Santos and David had been awakened and rousted out of bed by Officers Darrell L. Cain and his partner Roy R. Arnold who were investigating a late-night burglary at a nearby gas station where money had been stolen from a cigarette machine — the boys matched a witness’ vague description. The boys said they had nothing to do with the burglary but were taken from their home as their foster-grandfather (an elderly man who spoke no English) watched, helpless, as they were handcuffed and placed in a squad car.

The boys were driven back to the scene of the burglary — a Fina station at Cedar Springs and Bookhout. Santos was in the front passenger seat, and Cain sat behind him in the backseat, next to David. Cain insisted the two boys were guilty and, in an attempt to coerce a confession, held his .357 magnum revolver to Santos’ head. He clicked the gun, as if playing Russian Roulette, telling Santos that the next time he might not be so lucky. The boys continued to insist they were innocent. And then, suddenly, Cain’s gun went off. Santos died instantly. Stunned, Cain said that it had been an accident. He and Arnold got out of the car, leaving 13-year-old David, still handcuffed, in the backseat of the police car — for anywhere from 10 minutes to half an hour — alone with his brother’s bloody body. (It was determined through fingerprint evidence that Santos and David did not break into the gas station that night.)

More in-depth articles about this horrible case can be found elsewhere, but, briefly, Cain (who had previously been involved in the fatal shooting of a teenaged African American young man named Michael Morehead) was charged with committing “murder with malice” and was found guilty. He was sentenced to 5 years in prison but ended up serving only two and a half years in Huntsville.

The killing of Santos Rodriguez sparked outrage from all corners of the city, but particularly in the Mexican American community. All sorts of people — from ordinary citizens to militant Brown Berets — organized and protested, persistently demanding civil rights, social justice, and police reform. If anything positive resulted from this tragic event, perhaps it was a newly energized Hispanic community.

**

I am ashamed to say that I was not aware of what had happened to Santos Rodriguez until I began to write about Dallas history a few years ago. This was an important turning point in the history of Dallas — for many reasons (namely in the Chicano movement, race relations, the fight for social justice, and an examination of Dallas Police Department procedure). Over the past week I’ve read a lot of the local coverage of the events of this case, and I’ve watched a lot of interviews of people who were involved, but perhaps the most immediate way I’ve experienced the events and emotions swirling about this case has been to watch television news footage shot as the story was unfolding. Thanks to the incredibly rich collection of TV news footage in the possession of the G. William Jones Film & Video Collection at SMU, I’ve been able to do that.

Below is footage shot by KDFW Channel 4, which has, most likely, not been seen since 1973. Some of it appeared in news reports, and some is just background B-roll footage shot to be edited into news pieces which would eventually air on the nightly news. The finished stories that aired do not (as far as I know) survive, but we have this footage. It’s choppy and chaotic and darts from one thing to the next, which is how a red-hot news story develops. Of particular interest is the short interview with 13-year-old David at 9:16 and the violent aftermath of what began as a peaceful march through downtown at 19:54.

A more comprehensive collection of the events — from just hours after the shooting to the conviction of Darrell Cain — can be found in this lengthy compilation of WFAA Channel 8 news footage. This and the Channel 4 footage are essential sources.

*

Santos Rodriguez (Nov. 7, 1960 – July 24, 1973)

Santos Rodriguez (Nov. 7, 1960 – July 24, 1973)

***

Sources & Notes

Top photo is a family photo, from the Austin American-Statesman article “Is It Time for Dallas to Honor Santos Rodriguez?” by Gissela Santacruz, here.

My sincerest thanks to Jeremy Spracklen at SMU for alerting me to these two collections of important historical news footage from KDFW-TV/Ch. 4 and WFAA-TV/Ch. 8, both of which are held by the G. William Jones Film & Video Collection, Hamon Library, Southern Methodist University. (All screenshots are from these two videos.)

An excerpt from the 1982 KERA-produced documentary “Pride and Anger: A Mexican American Perspective of Dallas and Fort Worth” (the Santos Rodriguez case is discussed) is on YouTube here.

“Civil Rights in Black & Brown” is a fantastic oral history project by TCU. I watched several of the interviews focusing on Santos Rodriguez, but I was particularly taken with the oral history of Frances Rizo — her 2015 interview is in two parts, here and here.

More on the events surrounding the killing of Santos Rodriguez can be found at the Handbook of Texas History site, here.

My continuation of this story can be found at the Flashback Dallas post “Santos Rodriguez: The March of Justice” — 1973,” here.

*

Copyright © 2018 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

1938 city directory

1938 city directory