Juneteenth at the Texas Centennial — 1936

The Hall of Negro Life at the Texas Centennial Exposition, Fair Park

The Hall of Negro Life at the Texas Centennial Exposition, Fair Park

by Paula Bosse

Juneteenth, the anniversary of the date that African American Texans learned they were freed from slavery, was celebrated at the Texas Centennial Exposition with a day of entertainment and exhibits. It was also the day that the Hall of Negro Life — a federally funded exhibition hall acknowledging and honoring the history and accomplishments of African Americans in the United States — was officially dedicated.

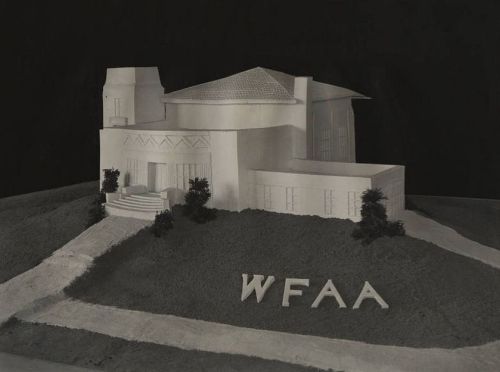

One of the more interesting things I’ve stumbled across is a drawing of the proposed building (published in J. Mason Brewer’s The Negro In Texas History in 1935). I don’t believe I’ve seen this before. It’s interesting to note the changes from original proposal to finished product.

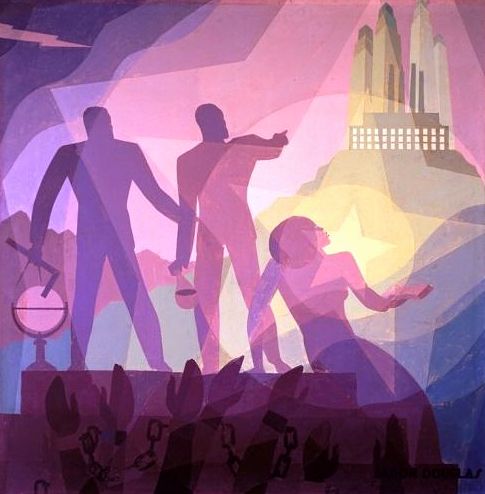

Among the large collection of art by black artists displayed in the Hall of Negro Life were four murals by the artist Aaron Douglas, depicting black history in Texas. Below are the two murals that survive, “Into Bondage” and “Aspiration.” These are incredible murals, and it must have been an emotional experience for those Juneteenth visitors in 1936 to be surrounded by all four powerful pieces in the lobby of a government-backed project that formally recognized the contributions of fellow African Americans.

“Into Bondage” by Aaron Douglas, 1936 (Corcoran Gallery of Art)

“Into Bondage” by Aaron Douglas, 1936 (Corcoran Gallery of Art)

“Aspiration” by Aaron Douglas, 1936 (Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco)

“Aspiration” by Aaron Douglas, 1936 (Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco)

***

Sources & Notes

Black-and-white photograph of the Hall of Negro Life from the Private Collection of Mary Newton Maxwell, Portal to Texas History, here.

Photo of proposed Hall of Negro Life from An Historical and Pictorial Souvenir of the Negro In Texas History, written by J. Mason Brewer (Dallas: Mathis Publishing Co., 1935).

“Into Bondage” by Aaron Douglas (1936) is from the collection of The Corcoran Gallery of Art.

“Aspiration” by Aaron Douglas (1936) is from the collection of The Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco. (There is an amazing interactive look at this painting here.)

More on the Hall of Negro Life, from the Handbook of Texas, here.

More on the Hall of Negro Life from The Crisis, the magazine of the NAACP, in the July, 1936 article “Negroes and the Texas Centennial” by Jesse O. Thomas, here.

How was this important Juneteenth celebration at the Texas Centennial covered by The Dallas Morning News? Well, the paper actually devoted a lot of space to the day’s events in a fairly lengthy article which appeared on June 20, 1936. I think the DMN editorial board probably thought they were being magnanimous in the amount of coverage given, but, really, the article — though brimming with a certain amount of probably well-intentioned jubilation — is so unremittingly racist that it’s actually shocking to see this sort of thing in print in a major newspaper. I encourage you to check out the article published on June 20, 1936 which carries the laboriously headlined and sub-headlined “Negroes Stage Big Juneteenth at Centennial; Dallas Eats Cold Supper and Cotton Patches Emptied as Thousands Inspect Magic City; Hall Is Dedicated; Dusky Beauties Prance; Cab Calloway Does His Stuff For Truckers.”

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

A. Harris ad (det) , 1936

A. Harris ad (det) , 1936