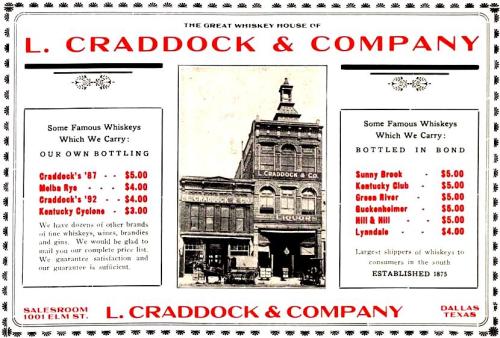

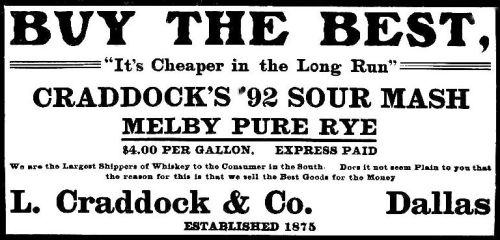

L. Craddock ad, 1912

L. Craddock ad, 1912

by Paula Bosse

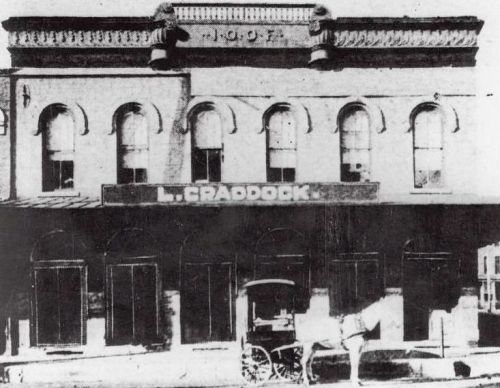

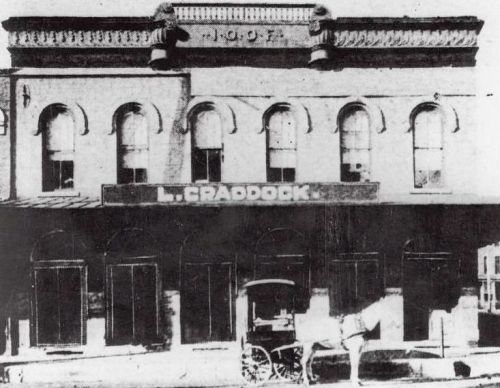

L. Craddock, an Alabama native born in 1847, arrived in Dallas in 1875 and opened a liquor business at Main and Austin streets in a building built by the Odd Fellows. It was a success, becoming one of the largest such businesses in a young, thirsty city.

Feeling a flush of civic pride, Mr. Craddock branched out beyond the retail world of alcohol sales, and in the late 1870s he opened the city’s second theatrical “opera house,” conveniently housed on the second floor of his liquor emporium, above his saloon and retail business. The theater was immensely popular and hosted the important performers and lecturers of the day, until the much larger Dallas Opera House arrived on the scene and siphoned off Craddock’s audiences. He closed the second-floor theater in the mid-1880s (a space which, presumably, continued to be used as an IOOF meeting hall) but kept the business on the ground floor.

The first location, at Main & Austin, with theater on second floor (1880s)

The first location, at Main & Austin, with theater on second floor (1880s)

In 1887 Craddock decided to change careers. He sold his company to Messrs. Swope and Mangold (more on them later) and retired from the liquor trade — if only temporarily. I’m not sure what prompted this somewhat unexpected decision (I’d like to think there was some juicy, illicit reason), but, for whatever reason, he decided to give real estate a whirl. Craddock was certainly a savvy wheeler-dealer and he probably did well buying and selling properties in booming Dallas, but (again, for whatever reason) he seems to have tired of real estate, and, by at least 1894 (if not sooner), he had returned to the whiskey trade and had built up an even more massive wholesale liquor business than before.

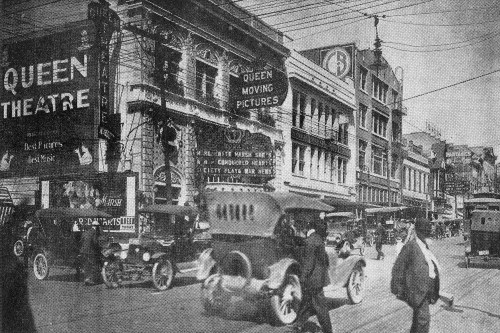

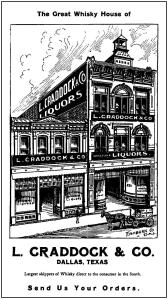

1907 (click for much larger image)

1907 (click for much larger image)

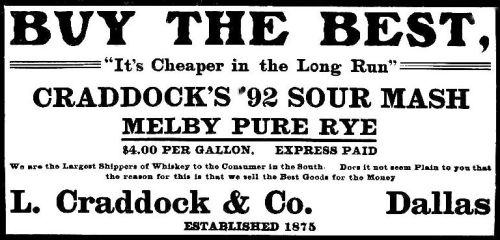

He had a new, larger building, this time on Elm, between N. Lamar and Griffin. In the company’s incessant barrage of advertising, he touted the company’s unequaled, unstoppable success as purveyors of the finest alcohol available. One ad even took on something of a hectoring, lecturing tone as it admonished the reader with this snappy tagline:

“We are the Largest Shippers of Whiskey to the Consumer in the South. Does it not seem Plain to you that the reason for this is that we sell the Best Goods for the Money.”

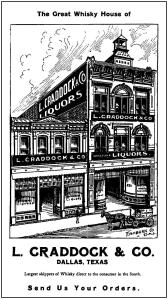

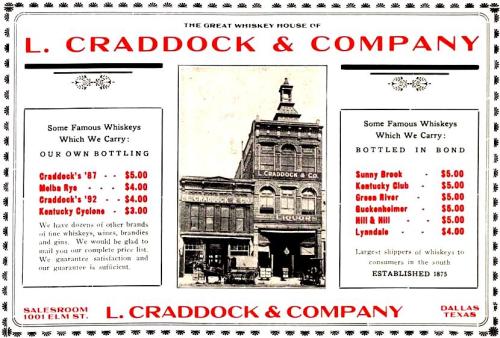

1906

1906

Arrogant or just supremely confident, Craddock was rolling in the dough for many, many years. Until … disaster struck. Prohibition. With the inevitable apocalypse about to hit the alcoholic beverage industry, L. Craddock threw in the towel and retired. For good this time. I’m sure many a faithful L. Craddock & Co. customer stocked up on as much as they could hoard in the final weeks of the prices-way-WAY-higher-than-normal going-out-of-business sale.

Craddock retired to Colorado, but in 1922, he returned to present to the city a valuable ten-acre tract of land in the old Cedar Springs area — land he asked be used as a park. Craddock Park remains a part of the Dallas Parks system today.

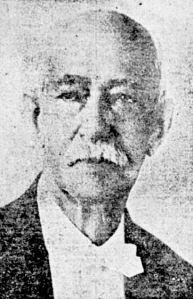

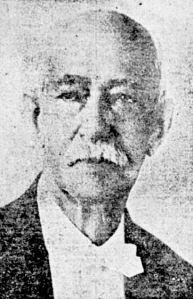

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 3, 1922

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 3, 1922

It’s interesting to note that in every article about Mr. Craddock that appeared during and after Prohibition — such as the articles reporting his generous gift to the city — there was never any mention of what kind of business he had been in or how he had made his great fortune. Even in his obituary. He was always vaguely described as a “pioneer businessman.”

Speaking of his obituary (which, by the way, was the place I actually saw his first name finally revealed — it was Lemuel), L. Craddock — Dallas’ great retailer of beer, wine, and spirits — died on December 2, 1933. Three days before the repeal of Prohibition. THREE DAYS. O, cruel fate.

**

ADDED: Interesting tidbit about a legal matter brought by Federal prosecutors. In 1914, Craddock was found guilty of “illicit liquor dealing” — shipping barrels of whiskey (labeled “floor sweep”) into the former Indian Territory of Oklahoma. Craddock wrote a check for the fine of $5,000 right there in the courtroom. The three men who actually did the deed were sentenced to a year and a day at Leavenworth. (I’m never sure how much faith to put in the Inflation Calculator, but according to said calculator, $5,000 in today’s money would be approaching $115,000. I think ol’ Lemuel was doing all right, money-wise. I’m guessing this “floor sweep” thing was not an isolated incident.)

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 19, 1914

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 19, 1914

***

Sources & Notes

Top L. Craddock & Co. ad from 1912.

Photograph of first location, with theater, from Historic Dallas Theaters by Troy Sherrod (Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2014).

Ad featuring rendering of second Craddock location at Elm & Poydras, signed Fishburn Co. Dallas, from 1906.

Photograph of L. Craddock from a Dallas Morning News interview in which he reminisces about the Craddock Opera House, published December 3, 1925. It’s an informative interview about early Dallas (like REALLY early Dallas) — the article can be read here.

Update: I’ve wondered if this building downtown is the Craddock building, cut down and uglified. The current address is 911 Elm (I assume that the addresses for that stretch of Elm changed when the cross-street configuration changed). The Dallas Central Appraisal District gives the construction date of that building as 1937, but the DCAD dates are frequently not accurate. I don’t know. It’s very similar (missing the third floor…) and in about the exact same spot. Looks like it to me. That poor 100-plus-year-old building needs some loving attention. Here is a Google street view from early 2014:

Most images in this post are larger when clicked.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

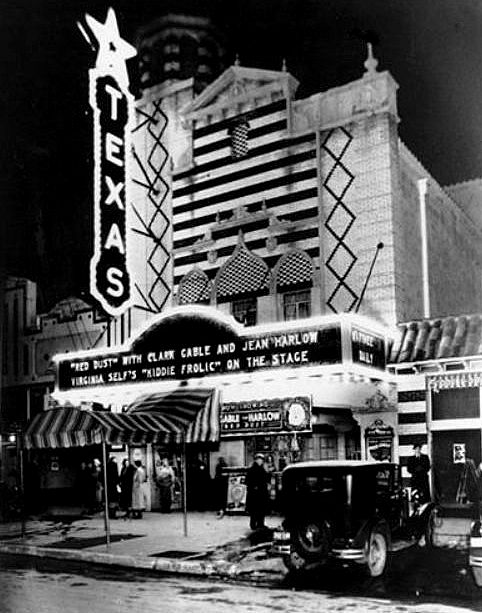

The “Texas”

The “Texas”