The Fountain: “A Resort for Gentlemen” — ca. 1911

by Paula Bosse

This postcard (which has a 1911 postmark) shows The Fountain, a well-appointed drinking establishment (not lacking in ceiling fans). The caption reads:

Meet me at the Fountain, a Resort for Gentlemen, 1518 Main Street, Dallas, Texas.

John H. Senchal, Propr.

Don’t fail to see the Greatest Fair on Earth at Dallas, Texas.

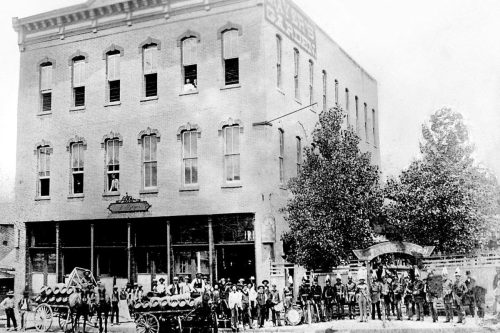

This bar-with-food was located on the south side of Main, steps away from the present location of Neiman Marcus. It was in the block seen in the picture below (it is just out of frame at the bottom right, next door to the Colonial Theater):

Main Street looking east from Akard

Main Street looking east from Akard

Its address was originally 350 Main — after the city-wide address change in 1911, it became 1518 Main. It appears to have opened in 1907 and was in business until at least 1918 (after Dallas voted to go “dry,” the former saloon became The Fountain Cafe). Here are a few early ads for the “High-Class Stags’ Cafe” in its early go-go “gentlemen’s resort” days:

Dallas Morning News, Oct. 1907

Dallas Morning News, Oct. 1907

A few years later, the owner, John Henry Senchal, opened Senchal’s Buffet and Senchal’s Restaurant and Rathskeller at 1614-1618 Main.

*

Johnnie Senchal — born in Galveston in 1875 to a French father and American mother — appears to have been a popular, civic-minded man’s-man. He frequently traveled with Dallas businessmen to other cities and states to act as a booster for the city. He also indulged in sporty activities such as being a regular wrestling referee and sponsoring horse races at the State Fair of Texas (in 1914 a $2,000 “Fountain Purse” was offered — in today’s money, more than $56,000!). One 1915 newspaper report said he was “probably the best known saloon man in the city.” He was very successful and was not hurting for money.

He also seems to have had a cozy relationship with members of the Dallas police department — a situation which is probably commonplace between saloon-owners and cops. One news story described how he had leapt to the defense of a policeman who was waylaid by a large group of men while he was walking prisoners to jail — a huge brawl broke out, and Senchal and the cop emerged victorious. Also — in a story which wasn’t fully explained — Senchal and another man ponied up $5,000 in bond money ($140,000 in today’s money!) for a Dallas policeman who was charged in the fatal shooting of a 17-year-old, Those are some strong ties between a saloonkeeper and the local constabulary, man.

In 1912 there was another confusing story concerning a man who had been arrested and convicted for being the owner/lessee/tenant of an establishment which was “knowingly permitted to be used as a place in which prostitutes resorted and resided for the purpose of plying their vocation. […] The house was a ‘disorderly house.’ Prostitutes resorted there and displayed themselves in almost a nude condition.” The man who was charged was seen there on a number of occasions “dancing with the prostitutes.” The man appealed his conviction because he had been charged with being the owner/lessee/tenant of this “bawdy house” — but the lessee/tenant was none other than Johnnie Senchal and another man. As far as I can tell, Senchal was not charged with anything regarding this case.

But a couple of years later, in 1914, he was charged with running a “disorderly house” (a term often meaning a bordello or gambling den, but also meaning a place which is frequently the site of disturbances and is generally considered to be a public nuisance). It seems Johnnie and other were offering “cabaret” entertainment which might gotten out of hand. From The Dallas Morning News:

Alleging that the cabarets are conducted as “disorderly houses,” [charges were filed] on behalf of the State of Texas against owners of three restaurants in the downtown section. Affidavits accompanying the petitions alleged that women were allowed to drink at the places and to act in an unbecoming manner. (DMN, March 12, 1915)

I’m not sure exactly what constituted “an unbecoming manner,” but Johnnie Senchal was one of the men charged. At the very same time he was fighting this violation of the cabaret ordinance, it was reported that “an involuntary petition in bankruptcy has been filed in the United States court here against John Senchal and J. O. Walker, partners in the saloon business on Main Street. The petition was filed by local brewery agents and whisky houses” (DMN, June 20, 1915). Bankrupt! Even though he was apparently rolling in dough for years, he was rather ironically pushed to bankruptcy because he couldn’t pay his own bar tab.

And so Johnnie put the barkeeper’s life behind him. And I mean he REALLY put it behind him: he became a fervent speaker at Anti-Saloon League events, saying that having been forced out of the saloon game was actually a godsend — he was quoted as saying that his profits increased 75-80% when he stopped selling alcohol and became a full-time restaurateur. That seems unlikely, but that’s where he was in 1918, an improbable evangelist for Prohibition.

Soon after, he and his family moved to Houston, where he opened a small cafe. On Oct. 9, 1929, after closing-time, Johnnie Senchal died in his cafe from a self-inflicted gunshot wound. He was 54 years old.

***

Sources & Notes

Postcard of The Fountain found on eBay.

Postcard of Main Street found on Flickr.

*

Copyright © 2022 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

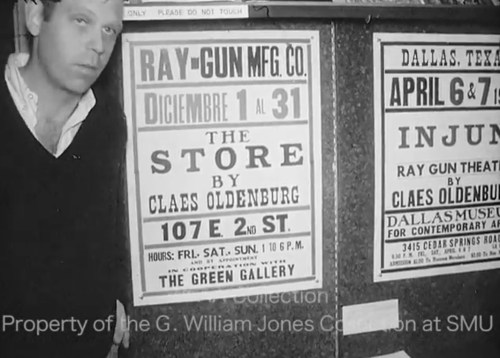

Claes Oldenburg at the DMCA, April, 1962 (WFAA Collection, SMU)

Claes Oldenburg at the DMCA, April, 1962 (WFAA Collection, SMU)

“1961” catalogue, via

“1961” catalogue, via

Dallas Herald, Dec. 13, 1881

Dallas Herald, Dec. 13, 1881

Nov. 24, 1901

Nov. 24, 1901

Anshel Brusilow

Anshel Brusilow

WFAA Collection, Jones Collection, SMU

WFAA Collection, Jones Collection, SMU WFAA Collection, Jones Collection, SMU

WFAA Collection, Jones Collection, SMU

WFAA Collection, Jones Collection, SMU

WFAA Collection, Jones Collection, SMU

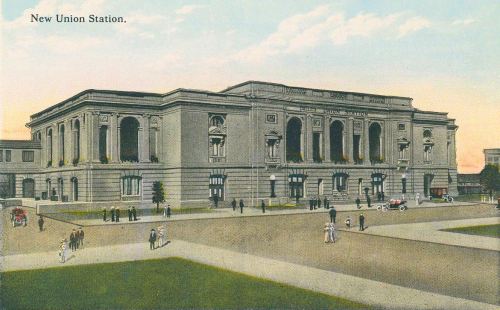

An impressive collection of architectural styles

An impressive collection of architectural styles