by Paula Bosse

Texlite. If you’re a lover of all-things-Dallas, you should know that name. Texlite made many, many, many, many, MANY enamel, electric, and neon signs, including, most famously, the rotating Flying Red Horse — Pegasus — which arrived in Dallas in 1934 to sit atop the city’s tallest building, the Magnolia Petroleum Building, serving as a beacon, a landmark, and as a sort of city mascot.

Texlite’s roots went back to 1879 when Italian immigrant Peter Samuel Borich (1849-1932) arrived in Dallas. His obituary noted that he was a graduate of the Royal Italian Naval School and that he served in the Italian Merchant Marine before he arrived in Dallas, where he established the Borich Sign Co. A very early location of his shop is said to have been on the current site of the Magnolia Building (and Pegasus), on Sycamore Street (now Akard). (See the post “19th-Century Sign-Painting and Real-Estating” for more about this location.) He appears to have been the go-to sign-painter for decades and was a very successful businessman.

The Borich company eventually branched out (and eventually became Texlite, a separate entitity) to become a pioneer in electric and neon signs: in 1926 Texlite built and sold the first neon sign west of the Mississippi, in St. Louis (their first neon sign in Dallas was a sign for the Zinke shoe repair store (1809 Main) which depicted an animated hammer tapping on a shoe heel).

The Borich sign company focused on painted or printed signs while Texlite handled the electric signs. P. S. Borich retired in the 1920s and moved to Los Angeles after the death of his wife. The last time the Borich company name appeared in the Dallas directory was 1930 (when it looks like it became United Advertising Corporation of Texas, owned by Harold H. Wineburgh, who was also a Texlite partner/owner).

During World War II, Texlite, like many manufacturers, jumped into war-production work, making airplane and ship parts; during the Korean War they made bomber fuselages.

I don’t know when Texlite went out of business (or was acquired and merged into another company). As successful as Texlite was (and it was incredibly successful), what more important achievement could it have had than to have been the maker of our iconic Pegasus?

*

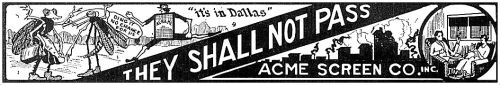

Here are a few random images from the Borich/Texlite history. First, a great ad from 1949, when Pegasus was a fresh 15-year-old. “It’s Time For a Spring Sign Cleaning.” (Click to see a larger image.)

1949 ad

1949 ad

And another ad, this one with a wonderful photo, from 1954.

1954 ad, via Flickr

1954 ad, via Flickr

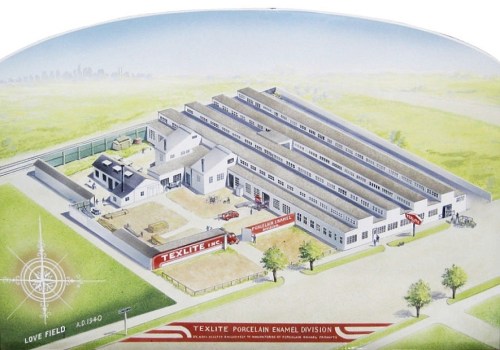

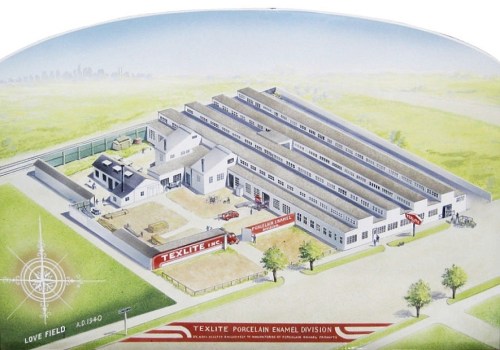

In 1949 Texlite built a huge new factory in an industrial area near Love Field, at 3305 Manor Way. Below is the architectural rendering. The caption: “New home of Texlite, Inc. is being completed at 3305 Manor Way at a total of $1,000,000. The new, two-story plant, providing 114,000 square feet of factory and office space, will provide facilities for trebling Texlite’s output. Grayson Gill is the architect, and O’Rourke Construction Company are the general contractors.” (Dallas magazine, Feb. 1949)

Below, the previous factory, located at 2900 Factory Street, also near Love Field:

I assume this 1940 sign was made by Texlite. Below are a couple of details, showing playful hints of Pegasus.

via Mecum Auctions

via Mecum Auctions

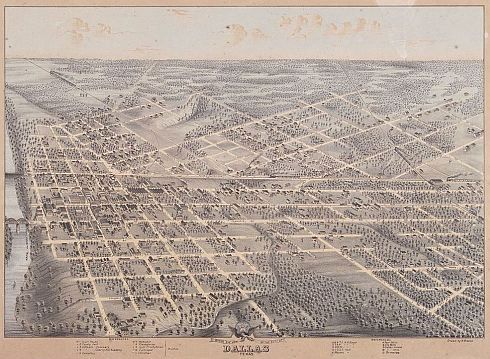

I wondered where Factory Street was — here it is on a 1952 map — it looks like it was absorbed into a growing Love Field.

1952 Mapsco

1952 Mapsco

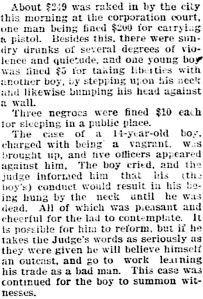

One of Texlite’s many theater clients was the Palace Theatre for whom they designed and installed a new electric sign in January, 1929 (at which time, by the way, the theater’s name was “officially” changed — however briefly — to the Greater Palace; the theater was renovated and enlarged, with a new emphasis on the Elm Street entrance rather than the entrance on Pacific).

Jan., 1929

Jan., 1929

Going back a couple of years, with the separate companies sharing ad space in the 1927 city directory:

1927 Dallas directory

1927 Dallas directory

And a photo of the Texlite building circa 1930:

Dallas Public Library

Dallas Public Library

The first ad I found which had both the “Borich” and “Texlite” names together was this one from 1923 for the Cloud-George Co., a women’s clothing boutique (1705 Elm) run by the somewhat notorious Miss A. B. Cloud.

Sept., 1923

Sept., 1923

The company occupied several locations over the years — the location in 1902 can be seen here, at the right, looking west on Pacific (from the Flashback Dallas post “Views from a Passing Train — 1902”).

1902, via Free Library of Philadelphia

1902, via Free Library of Philadelphia

Dallas directory, 1902

Dallas directory, 1902

P. S. Borich’s sign-painting wasn’t restricted only to businesses — he was also regularly retained by the city to paint street signs.

Dallas Herald, Aug. 6, 1886

Dallas Herald, Aug. 6, 1886

And, below, the earliest ad I could find — from 1879, the year Borich arrived in Dallas. (Thanks to this ad, I can now add “calsomining” to my vocabulary.)

Norton’s Union Intelligencer, Nov. 1, 1879

Norton’s Union Intelligencer, Nov. 1, 1879

**

Here’s an interesting little bonus: a Pegasus “mini-me” in Billings, Montana, created with help from the Pegasus experts in Dallas (click for larger image).

Billings Gazette, May 22, 1955

Billings Gazette, May 22, 1955

***

Sources & Notes

Top image is a detail from a 1949 ad found in the Feb., 1949 issue of Dallas, the magazine published by the Dallas Chamber of Commerce.

Photo showing the exterior of the Texlite building circa 1930 is from the collection of the Dallas Public Library, Call Number PA87-1/19-59-36.

Check out another Texlite sign which I wrote about in the Flashback Dallas post “Neon Refreshment: The Giant Dr Pepper Sign.”

I’m always excited to see places I write about show up in old film footage. Watch a short (20-second) silent clip of Texlite workers striking in June, 1951 at the 3305 Manor Way location in WBAP-Channel 5 footage here (the workers were on strike in a wage dispute — more info is in the news script here); film and script from the KXAS-NBC 5 News Collection, University of North Texas, via the Portal to Texas History.

The company made tons of signs and exteriors for movie theaters around the country, including the Lakewood Theater (whose sign was recently re-neonized!).

Thank you, Signor Borich!

*

Copyright © 2020 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

McCoy homestead… (photo: Dallas Historical Society)

McCoy homestead… (photo: Dallas Historical Society) Col. John C. McCoy

Col. John C. McCoy![]()