Mardi Gras: “Our First Attempt at a Carnival Fete” — 1876

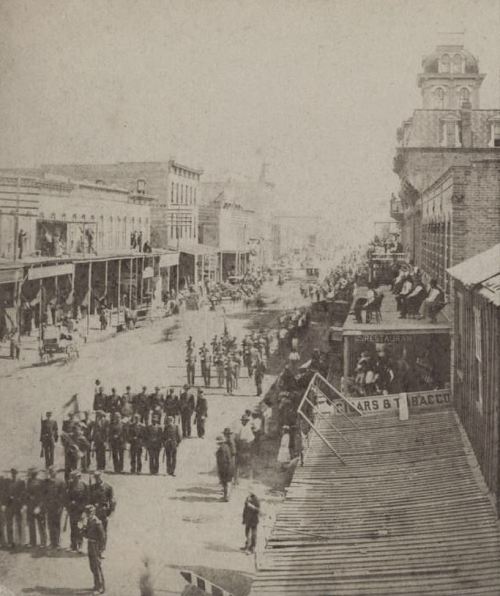

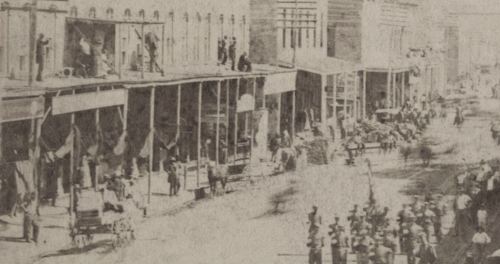

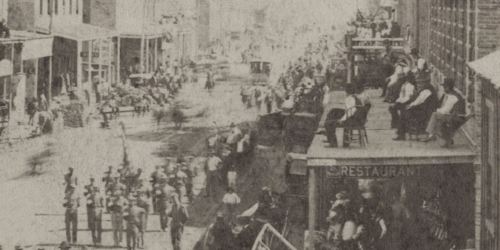

When cotton was Rex (click for much larger image)

When cotton was Rex (click for much larger image)

by Paula Bosse

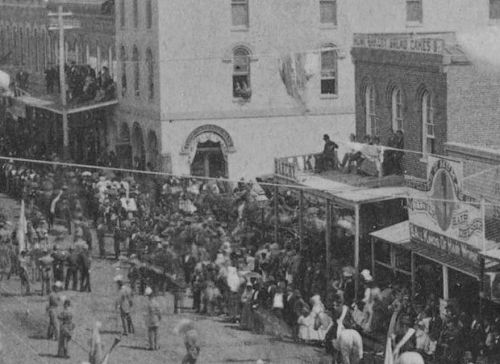

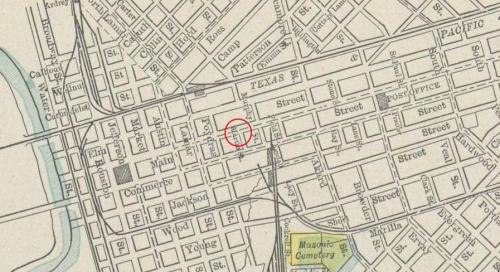

In the 1870s, if a Dallas resident wanted to celebrate the glitzy revelry of Mardi Gras with a parade and balls and didn’t want to travel all the way to New Orleans, the place to go was Galveston. Galveston had a lock on Texas Mardi Gras galas. But Dallas being Dallas, there were soon plans to stage a massive Carnival right here. The day-long celebration debuted on February 24, 1876, which, oddly, was on a Thursday. (Mardi Gras that year was actually on Tuesday, Feb. 29, and it was probably celebrated early in Dallas so as not to interfere with the hey-we-got-here-first celebrations in New Orleans and Galveston.)

It was estimated that the festivities cost the city more than $20,000 (which, if the Inflation Calculator is to be believed, would be the equivalent of almost $450,000 in today’s money). The city was cleaned up in preparation for the anticipated onslaught of visitors and was decorated with flags and bunting along the lengthy parade route of Main, Elm, and Commerce streets. Revelers had elaborate costumes made for the processions and the grand masked balls, some with fabric imported for the occasion from France

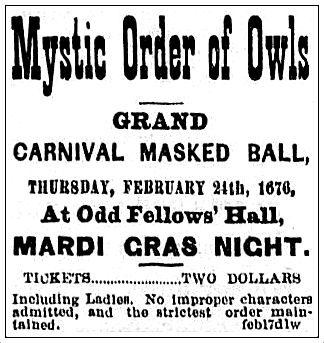

Dallas Herald, Feb. 18, 1876 (not 1676!)

Dallas Herald, Feb. 18, 1876 (not 1676!)

The Dallas Herald and The Dallas Commercial were incessant in their whipping up of excitement for the big day. And it worked. People streamed into town from all over Texas. Hotels were packed, and it was estimated that over 20,000 spectators watched one or both of the day’s parades.

The following day, The Dallas Herald apparently devoted their entire front page to coverage of the event, under this wordy headline:

A Day in Dallas, Our First Attempt at a Carnival Fete. The City Aglow with Enthusiasm and Wild with Rollicking Revelry. Visit of King Momus — His Cordial Reception by the People — The Procession in His Honor. The Season of Merry-Making Brought to a Happy Close with Balls and Bouts — Well Done, Dallas!

(Sadly, this issue is not available online, perhaps because there were none found to scan as it sold out more than five editions and was probably the paper’s best-selling edition to-date.)

Dallas’ first Mardi Gras had been an unqualified triumph, and newspaper editors and city leaders were beside themselves with joy. The parade — and the city — had been covered enthusiastically and favorably by newspapers around the country, and the success of the huge celebration was seen as having been better advertising for the exuberant and growing city than could ever have been hoped.

Galveston? Pffft!

**

A few tidbits from that first Mardi Gras.

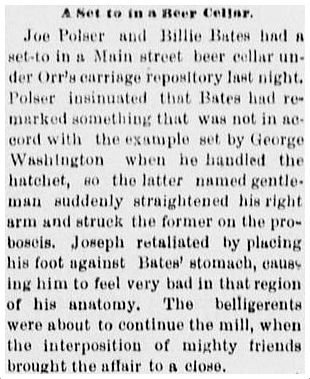

There were very few “incidents” reported surrounding the festivities. That’s not to say there weren’t a lot of incidents that occurred that day, just that not a lot of them found their way into the newspapers (apparently whiskey was free-flowing all day long, and one suspects there were “incidents” aplenty connected with that). Among the very few non-“jolly” things that happened on Carnival Day and the day following included the following:

- A small boy had been run over by a carriage (“but not dangerously hurt”)

- A child and a horse had been burned severely when a can of gasoline was thrown into a bonfire “to increase the flame”

- A member of the Stonewall Greys who had participated in the noontime parade had fallen whilst “foolishly scuffling” and had “received a slight but painful wound from a bayonet”

Also, there was some sort of “fireball discharged from a rocket” which caused some consternation:

Dallas Herald, Feb. 26, 1876

Dallas Herald, Feb. 26, 1876

*

All residences and businesses along the parade route during the evening procession were “commanded” to be illuminated. Even if gasoline-fueled bonfires were raging along the parade route, the elaborate procession was probably poorly lit.

*

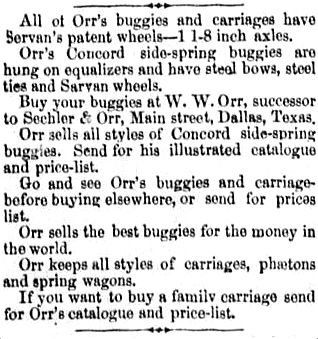

My favorite “float” was the huge wagon of lumber meant to draw attention to East Texas timber and the thriving lumber industry in Dallas. One report said “the immense moving forest of pine” was drawn by “32 yoke of oxen” — another said “nearly 100 Texan steers.” Whatever it was, that must have been spectacular to see.

Dallas Herald, Feb. 26, 1876

Dallas Herald, Feb. 26, 1876

*

The massive amount of publicity and praise that Dallas received quite clearly irked other cities. Austin seemed especially perturbed. There had been a small outbreak of smallpox in McKinney preceding the big day, and several digs at Dallas (like the one below) appeared in newspapers around Texas, accusing the city’s leaders of knowingly endangering the welfare of the entire state just so they could put on their little parade. The exaggerated furor passed fairly quickly, and the het-up schadenfreude expressed by rival cities was amusing.

Austin Weekly Standard, Mar. 16, 1876

Austin Weekly Standard, Mar. 16, 1876

*

An invitation issued by the Mystic Revellers:

Colton Greene Collection, Memphis Public Libraries

Colton Greene Collection, Memphis Public Libraries

*

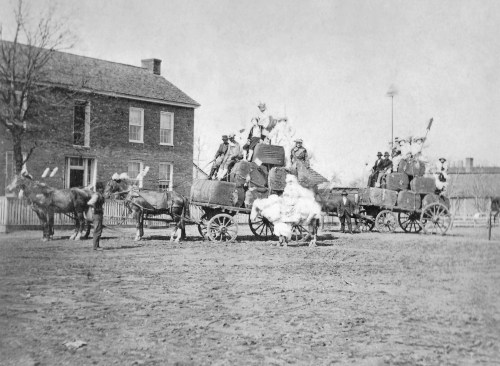

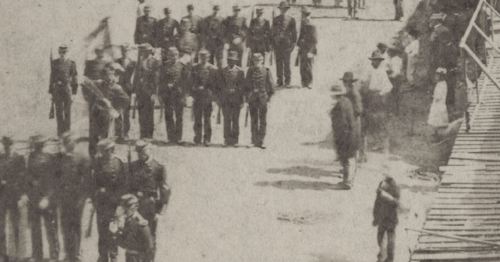

The photo at the top shows the parade wagons representing the brand new Dallas Cotton Exchange (which seems to have been organized the previous month). As described in The Galveston Daily News, the Cotton Exchange’s offering “represent[ed] King Cotton enthroned on six bales of cotton, with numerous subjects appropriately costumed, and occupying two cars” (Feb. 25, 1876). Below are a couple of magnified details of the photo. I’m not sure, but it looks as if the horse and rider in the foreground are covered with cotton. Like tarring and feathering … but fun … and with cotton. The King of Cotton is surrounded by what look like henchmen. The masked man on the right in the elaborate costume is both cool and kind of creepy. (Click both photos for larger images.)

***

Sources & Notes

Top photo appeared in the book Historic Photos of Dallas by Michael V. Hazel (Nashville: Turner Publishing Co., 2006); photo from the Dallas Historical Society.

Newspaper clippings as noted.

To read the coverage of Dallas’ Mardi Gras parades and balls — “a grand pageant and general jollification” — see the front page of The Galveston Daily News (Feb. 25, 1876), here (third column, top of page — zoom controls are on the left side of page).

I wrote a previous post called “Mardi Gras Parade in Dallas — ca. 1876” which features a photograph which might be from this first Mardi Gras. That post and photo can be seen here.

Happy Mardi Gras!

Dallas Herald, Feb. 24, 1876

Dallas Herald, Feb. 24, 1876

Photos larger when clicked.

*

Copyright © 2015 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

“Go to Ben Loeb’s” — 1877 advertisement

“Go to Ben Loeb’s” — 1877 advertisement The exclamation mark is a nice touch — 1878

The exclamation mark is a nice touch — 1878 Dallas Herald, Dec. 30, 1877

Dallas Herald, Dec. 30, 1877 Galveston Daily News, July 28, 1889

Galveston Daily News, July 28, 1889 Dallas Morning News, July 28, 1889

Dallas Morning News, July 28, 1889

Dallas Daily Herald, Nov. 21, 1874

Dallas Daily Herald, Nov. 21, 1874

Dallas Herald, June 2, 1878

Dallas Herald, June 2, 1878 Dallas Herald, June 3, 1880

Dallas Herald, June 3, 1880 Dallas Herald, Aug. 12, 1883

Dallas Herald, Aug. 12, 1883

Greenwood Cemetery, Dallas (photo: David N. Lotz)

Greenwood Cemetery, Dallas (photo: David N. Lotz)