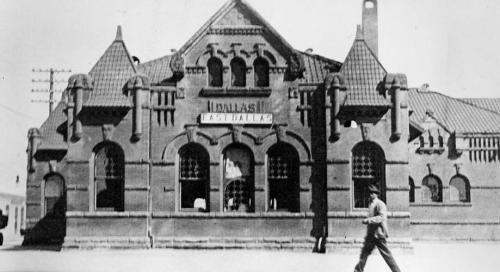

The Old Union Depot in East Dallas: 1897-1935

From the collection of Art Hoffman (click for larger image)

From the collection of Art Hoffman (click for larger image)

by Paula Bosse

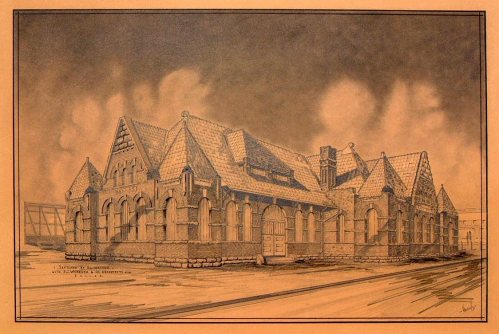

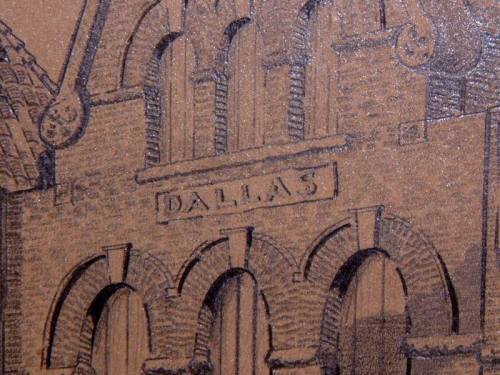

I saw the above rendering of the old East Dallas rail depot posted recently in a Dallas history group. It was bought several years ago by Art Hoffman who was told it had belonged to a former employee of the Houston & Texas Central Railroad (which, along with the Texas & Pacific, served this station). It’s an odd thing for an architect to sketch — a boarded-up railroad depot. I couldn’t find anything on E. L. Watson, the architect who did the rendering (perhaps a member of the Watson family who were prominent Dallas contractors?), and I couldn’t find any connection between the depot and the F. J. Woerner & Co. architectural firm. The drawing might have been done in 1931, with what looks like “31” next to the artist’s signature. Could the drawing have been done merely as a study for E. L. Watson’s portfolio?

But back to the building itself. It was referred to by all sorts of names: Union Station, Union Depot, East Dallas Depot, Old Union Station, etc. With all these permutations, it took considerable digging to determine exactly when it had been built and when it had been demolished.

A couple of stations had previously occupied this site (about where Pacific Avenue and Central Expressway would cross), the first being built in 1872 at the behest of William H. Gaston who was developing the area, well east of the Dallas city limits. Due to the presence of the railroad, the area grew quickly, and in 1882, it was incorporated as the city of East Dallas. It thrived and continued to grow and on January 1, 1890 it was annexed and became part of the city of Dallas.

Location of depot in red — map circa 1890-1900 (click to enlarge)

Location of depot in red — map circa 1890-1900 (click to enlarge)

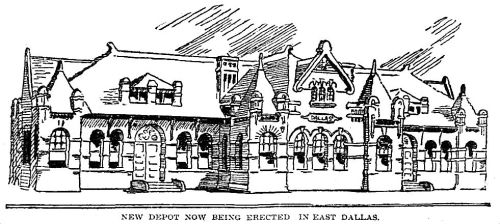

The depot pictured in the drawing above was built in 1897. The previous station, a woefully inadequate and outdated “shanty,” was, by early 1897, being nudged toward demolition in order to remain competitive with the new Santa Fe depot then under construction. In the Feb. 10, 1897 edition of The Dallas Morning News, it was referred to as “the present eye-sore in East Dallas” which would be better off “abandoned and used for kindling wood.”

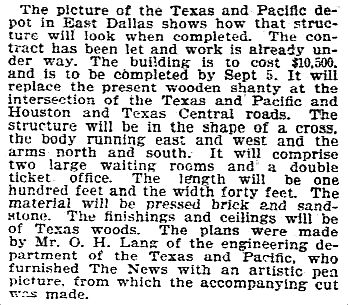

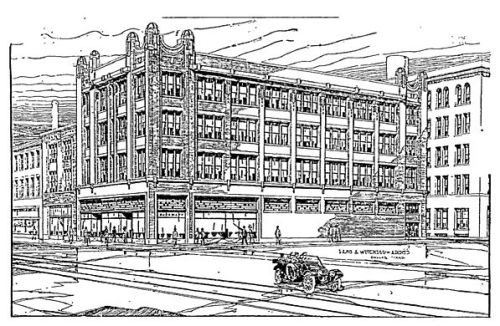

On April 4, 1897, it was reported that plans for a new Texas & Pacific passenger depot were nearly completed. By the beginning of June, the shanty had been torn down, and on June 6, 1897, the drawing below appeared in the pages of the Morning News, giving the people of Dallas a first look at what the much grander station would look like when completed. (It’s unfortunate that the actual architectural rendering was not used, but, instead, a more rudimentary staff artist’s version was printed.) The accompanying information revealed that the new depot had been designed by Mr. O. H. Lang, an architect who worked in the engineering department of the Texas & Pacific Railroad. This was an exciting tidbit to find, because I had wondered who had designed the structure but had been unable to find this elusive piece of information. And it was Otto Lang! Eight years after designing this railroad depot, Lang and fellow architect Frank Witchell would form the legendary firm of Lang & Witchell, and they would go on to design some of Dallas’ most impressive buildings.

Dallas Morning News, June 6, 1897

Dallas Morning News, June 6, 1897

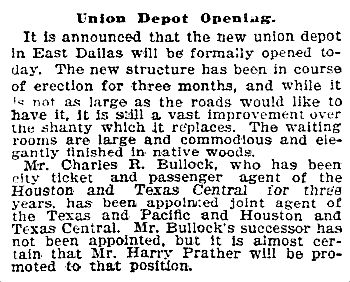

The building was completed fairly quickly, and its official opening was announced on Oct. 12, 1897.

DMN, Oct. 12, 1897

DMN, Oct. 12, 1897

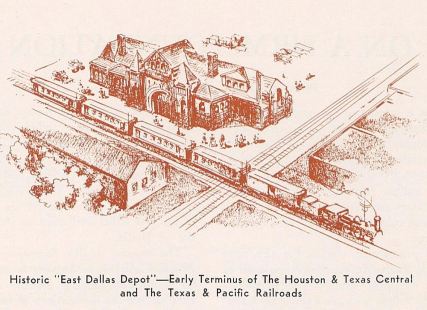

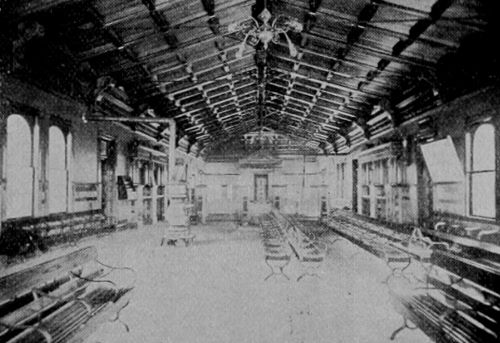

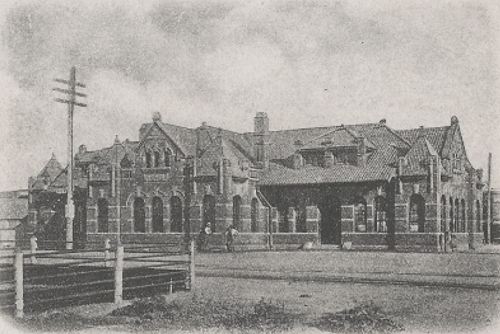

Here’s what the station looked like soon after it opened for business, from an 1898 Texas & Pacific publication (click for larger images):

Much better than a shanty!

Below in another early photo of the depot:

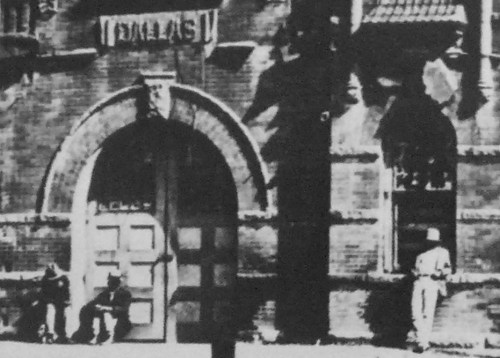

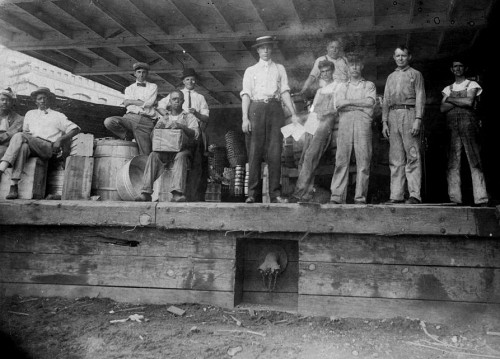

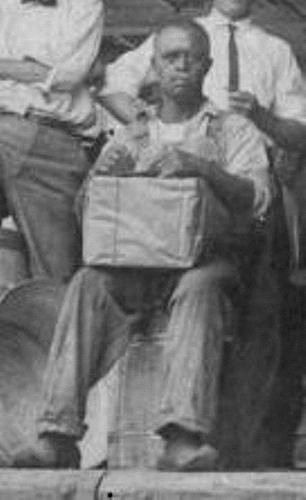

Can’t pass up an opportunity of zooming in on a detail:

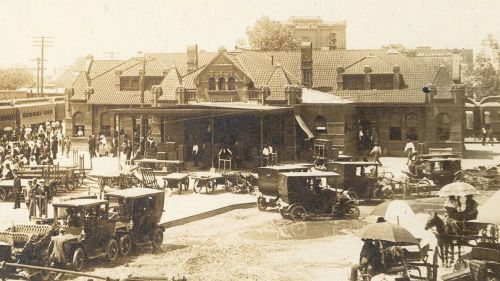

Here it is around 1910, a hotbed of activity, now with the addition of automobiles:

The station served an important role in the growth of (East) Dallas and in the everyday lives of its residents for almost twenty years, but in 1916 the many “independent” passenger and freight depots that had been spread out all over town were shuttered, per the Kessler Plan’s directive to consolidate and run all the rail lines in and out of the new Dallas Union Terminal. (This was when the word “old” began appearing ahead the East Dallas station whenever it was mentioned.)

So what became of the East Dallas depot? From “Relic of City of East Dallas Being Demolished,” a Dallas Morning News article from Jan. 20, 1935:

Last use of the depot for railroad purposes came in 1933 when it was abandoned as a freight station in August of that year. After that it was used as a station for interviewing destitute clients for the relief board but for several months has been boarded up.

So that original rendering may not have been done in 1931 after all (unless it was a high-concept architect’s vision of what the depot would look like one day all boarded up…).

At some point it was determined that the station would be torn down. It may have been one of those beautify-the-city projects done in preparation for the Texas Centennial Exposition the next year, but it was probably time for the building to come down. It was January of 1935, at the height of the Great Depression, and not only did the city make it a point to hire laborers on relief to assist in the demolition, but it also approved the use of salvaged materials from the site to be used in building homes for “destitute families.”

Relief Administrator E. J. Stephany received approval Saturday of a project to get men to tear down the old structure and use the materials in building homes for destitute families and work is expected to start immediately. (“East Dallas Station To Be Torn Down and Converted Into Homes,” DMN, Jan. 13, 1935)

Demolition of the depot — which The News called “The Pride of the Gay Nineties” — began on January 18, 1935. The first solemn paragraph of an article reporting on the razing of the landmark is below.

Shorn of all the dignity it possessed for years as the East Dallas Union Depot, the old red structure near the intersection of Central and Pacific avenues began crumbling beneath the blows of wrecking tools wielded by laborers from the Dallas County relief board Friday.” (“Relic of City of East Dallas Being Demolished,” DMN, Jan. 20, 1935)

The red stone slabs bearing the word “Dallas” (3 feet long, 18 inches thick) were offered to the Dallas Historical Society “for safekeeping.”

So did that relief housing get built? Sort of. All I could find was an article from June, 1935, which states that one little building was constructed with some of the brick and stone from the razed depot. It wasn’t a house for the needy but was, instead, headquarters for relief caseworkers in donated park land in Urbandale. Presumably there was housing built somewhere, but all that brick and stone salvaged from the old depot may not have been used for its intended purpose. BUT, there is this tantalizing little tidbit:

As a reminder of the historic antecedent, the new structure [in Urbandale Park] has as a headpiece for its fireplace the large carved stone bearing the name Dallas. (“Relief Structure Made of Materials From Razed Depot,” DMN, June 20, 1935)

Does this mean that the Dallas Historical Society might still have the second slab? If not, what happened to it?

I checked Google Maps and looked at tiny Urbandale Park at Military Parkway and Lomax Drive, just east of S. Buckner, but I didn’t see anything, so I assume the building came down at some point. (UPDATE, 3/20/16: Finally got around to driving to this attractive park. Sadly, the little building is no longer there.)

It would have been nice if that little bit of the old depot had survived — a souvenir of an important hub of activity which sprang to life when memories were still fresh of East Dallas being its own separate entity — the “David” Dallas to its neighboring “Goliath” Dallas. I would love to learn more about what might have happened to that “Dallas” sign which, for a while, hung over the fireplace of an odd little building in an obscure park in southeast Dallas where it lived out its days in retirement.

**

Since I keep adding photos of the depot to this post, I’m going to just start putting new additions (with captioned and linked sources) here:

DeGolyer Library, SMU

DeGolyer Library, SMU

DeGolyer Library, SMU

DeGolyer Library, SMU

“Your Dallas of Tomorrow” (1943), Portal to Texas History

***

Sources & Notes

Original rendering of the old Union Depot at East Dallas by E. L. Watson is from the collection of Art Hoffman, used with his permission.

More on architect Frank J. Woerner (who designed, among other things, the Stoneleigh Hotel), here (see p. 10 of this PDF).

History of Old East Dallas (and the city of East Dallas), here and here.

More on architects Lang & Witchell here, with an incredible list of some of the buildings designed by their firm here.

1898 photos of the depot’s exterior and interior from Texas, Along the Line of the Texas & Pacific Ry. (Dallas: Passenger Department of the Texas & Pacific Railway, [1898]).

Photo immediately following the photos from the T & P book is from a postcard, found on Flickr, here.

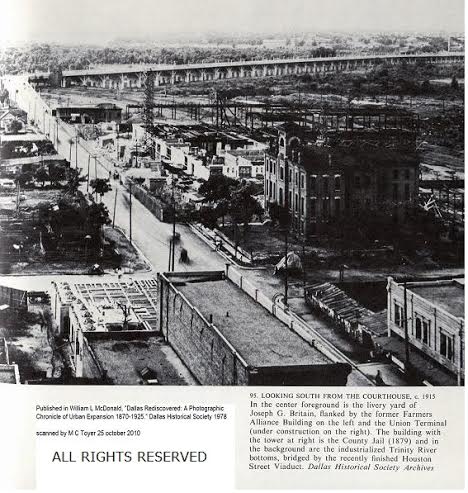

Photo (and accompanying detail) immediately following that is from Dallas Rediscovered by William L. McDonald (Dallas: Dallas Historical Society, 1978). (McDonald identifies the photo as being “c. 1890” — well before the station was built in 1897.) From the collection of the Dallas Historical Society.

Photo of the depot with automobiles is a detail of a larger photograph from the collection of George A. McAfee photographs in the DeGolyer Library, Central University Libraries, Southern Methodist University. The original can be seen here.

Photograph dated 1916 from The Museum of the American Railroad, via the Portal to Texas History site, here.

More information in these Dallas Morning News articles:

- “East Dallas Station To Be Torn Down and Converted Into Homes” (DMN, Jan. 13, 1935)

- “Relic of City of East Dallas Being Demolished” (DMN, Jan. 20, 1935) — very informative

- “Historical Society Will Be Given Slabs of Former Station” (DMN, Jan. 31, 1935)

- “County Gets Land To Install Relief Depot; Later Park” (DMN, Feb. 27, 1935

- “Relief Structure Made of Materials From Razed Depot; Station Occupies Land in Urbandale Donated to County For Park” (DMN, June 20, 1935)

- “Salvaged Materials Go Artistic” (DMN, June 20, 1935) — photo of “relief structure” which accompanied above article

More photos of this immediate area can be found in these posts:

- “The Union Depot Hotel Building, Deep Ellum — 1898-1968,” here

- “The Gypsy Tea Room, Central Avenue, and the Darensbourg Brothers,” here

Many of the pictures and articles can be clicked for larger images.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

DMN, Jan. 1, 1909

DMN, Jan. 1, 1909

DMN, Aug. 11, 1914

DMN, Aug. 11, 1914

1890

1890

ca. 1910-15

ca. 1910-15 Mrs. Morrill’s house at Ross & Harwood, 1894

Mrs. Morrill’s house at Ross & Harwood, 1894 The Morrill house — next stop: demolition, 1920

The Morrill house — next stop: demolition, 1920

Change is imminent. (Dallas Morning News, July 26, 1900)

Change is imminent. (Dallas Morning News, July 26, 1900)