Photo by Silver Lighthouse/Flickr

Photo by Silver Lighthouse/Flickr

by Paula Bosse

Here’s a topic that isn’t very sexy, but it’s one of those mammoth-scale city-wide operations that had to be done, but no one wanted to tackle it because it was a huge undertaking and it was going to be a big hassle: re-numbering the streets. All of them. Throughout the entire city. I wasn’t aware that something like this had ever happened until I started using old criss-cross directories to try to pinpoint the location of old buildings that were originally built on streets that no longer exist (such as Poydras and Masten).

Why, for instance, is the current address of the Majestic Theatre 1925 Elm St., but in 1909 that same parcel of land on Elm had an address of 463 (-ish)? Weird, huh? Obviously street numbers changed at some point, but when? And why? Eventually I zeroed in on 1910 or 1911 as the year when addresses seemed to have changed, but I was having a hard time finding any information about what prompted the change in the first place. Until I hit on the key phrase “century system.” After that, my search became much easier.

As far back as the 1880s, the city seemed poised to address the haphazard street numbering situation, as it was causing “endless confusion” — the powers-that-be had even seemed to settled on the “century system” (so called because each block is numbered up to 100, with a new hundred starting in the next block). But progress moves at a snail’s pace in city government, and the plan didn’t start picking up steam until fifteen or twenty years later.

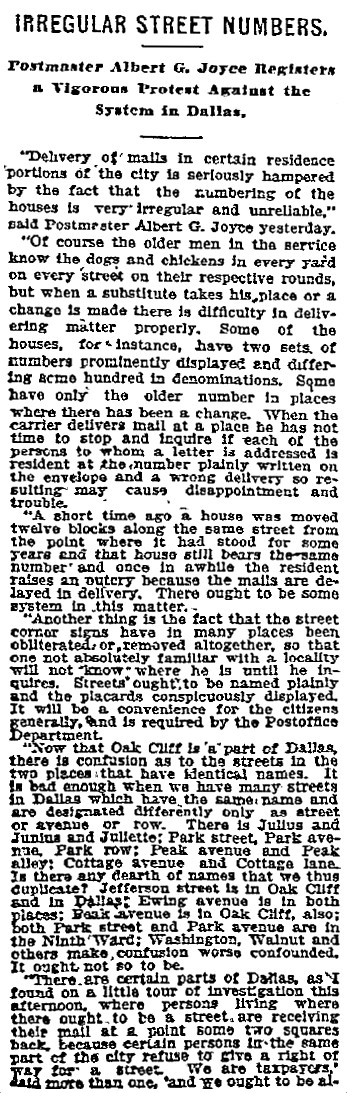

In the early days of the 20th century, the numbering of Dallas streets was, as one mail carrier described it, “freakish.” Numbers weren’t always consecutive. Sometimes odd and even numbers were on the same side of the street. Sometimes a run of numbers would suddenly start all over again. Houses sometimes had TWO numbers. People would move and expect to take their number with them. Buildings and houses often had NO numbers. Street signs were few and far between, and it wasn’t uncommon for street names to be duplicated in different parts of town. As you can imagine, unless you were intimately familiar with the area or neighborhood, chances were that you weren’t going to be able to find anything. Unsurprisingly, the real pressure to come up with some sort of logical, uniform street numbering system came from the city’s postmasters and postal employees (that they managed to regularly deliver mail to the proper recipients is just short of miraculous).

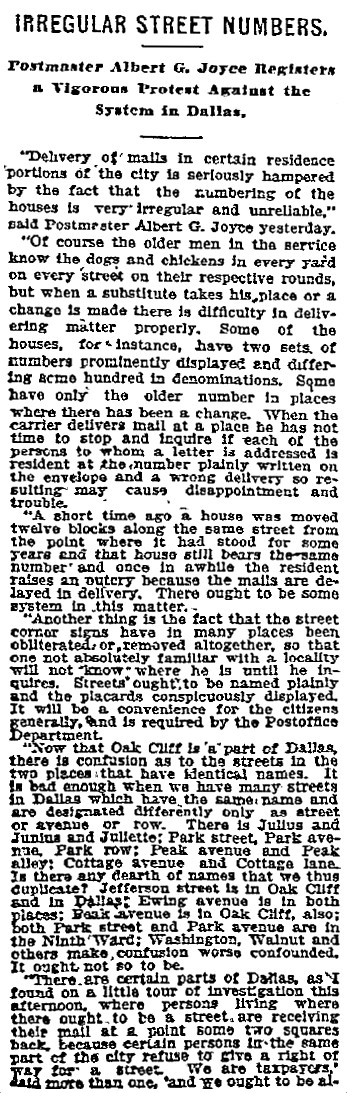

Postmaster Albert G. Joyce (one in a line of several postmasters who tried to effect change over the years) wrote an impassioned/frustrated plea for action in 1904:

(DMN, May, 18, 1904)

(DMN, May, 18, 1904)

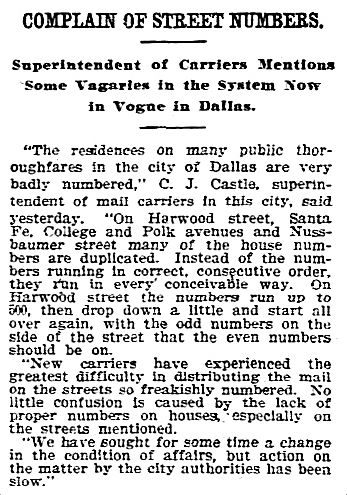

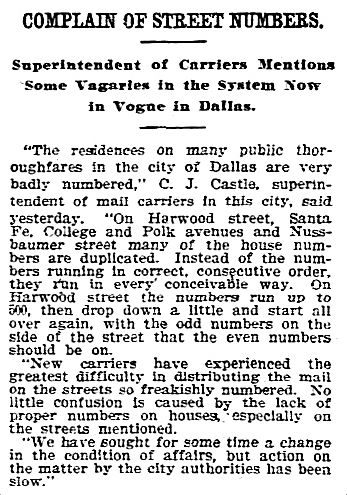

Everyone agreed that something needed to be done — especially as the city’s population was growing at an astronomical rate, but … nothing got done. Here, at the end of 1907, another exasperated postal employee shared examples of the problem:

(DMN, Dec. 7, 1907)

(DMN, Dec. 7, 1907)

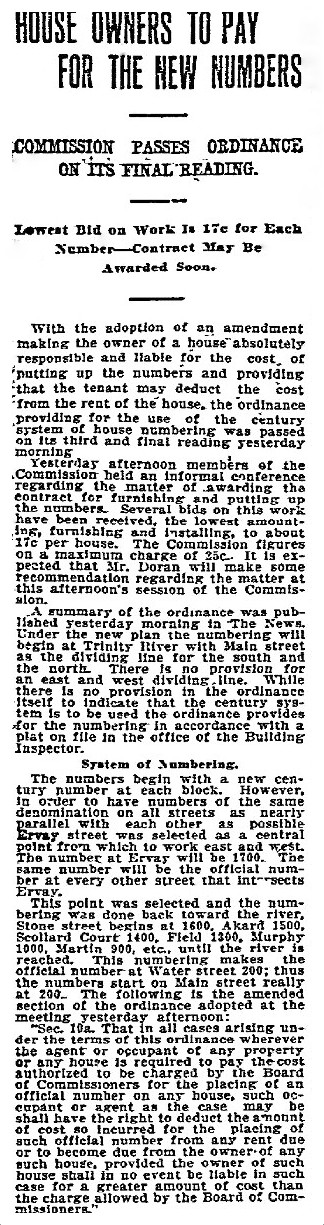

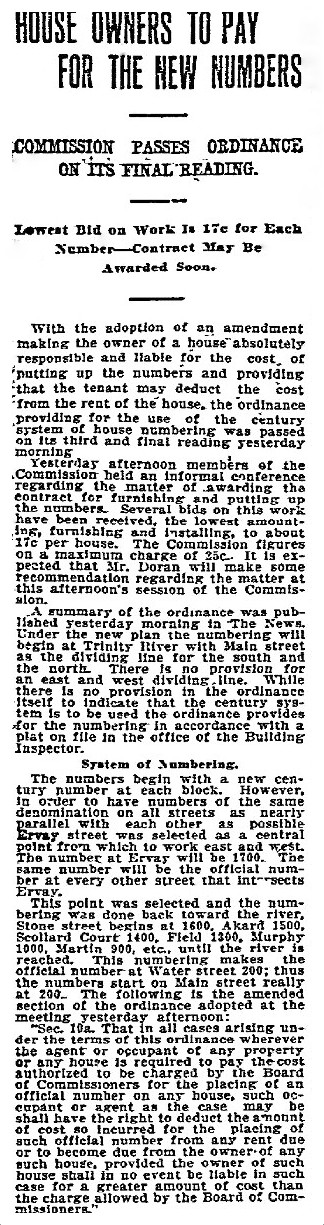

By 1909, a plan was finally starting to come together. This article describes how the numbering system would be implemented downtown, starting from the Trinity River, with Main and Ervay being the east-west and north-south anchors:

(DMN, Dec. 17, 1909)

(DMN, Dec. 17, 1909)

Even though the plan had basically been decided on, it wasn’t put into action for at least a year. There were three main reasons to delay the implementation: city directories had already been compiled and were to be issued soon, the 1910 census survey was about to begin, and the post office (which would bear the brunt of the impact of the drastic change) asked that the changeover take place before or after the busy holiday season.

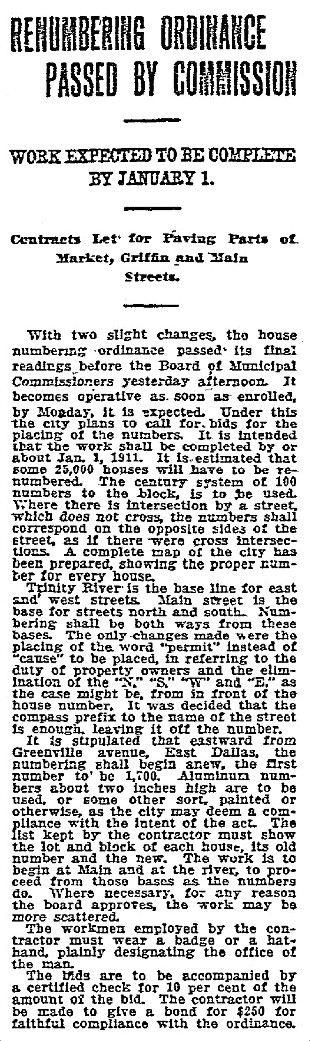

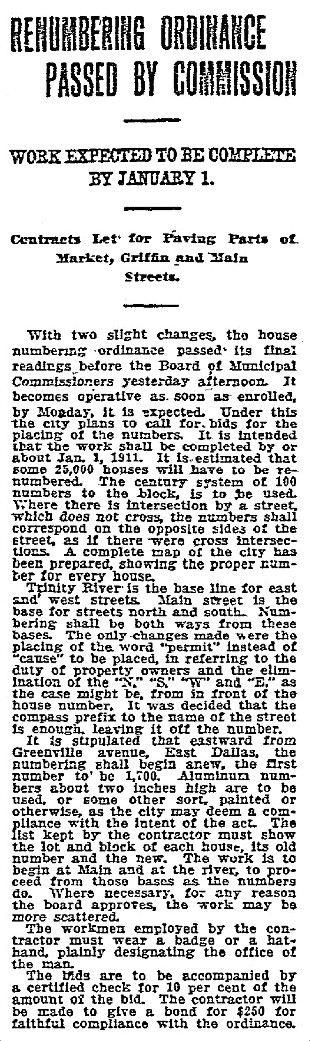

By the end of 1910, the final details had been hammered out. The main change to the previous version of the plan was that the city, rather than the property owners, would pay for the re-numbering. Also, I don’t know if this was a new detail or not, but there is mention here that numbering east of Greenville Ave. would “begin anew.” The re-numbering was expected to be completed in January, 1911.

(DMN, Oct. 1, 1910)

(DMN, Oct. 1, 1910)

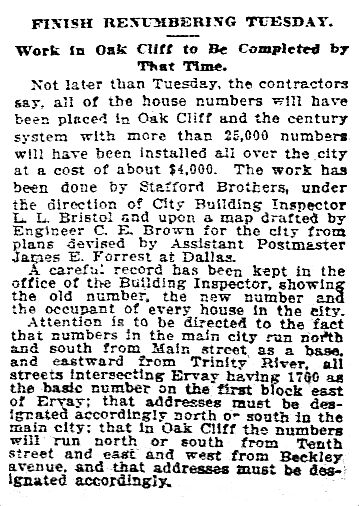

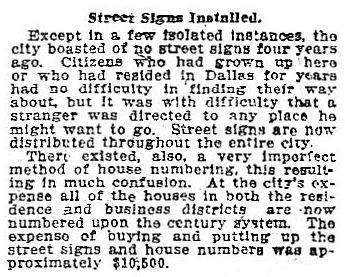

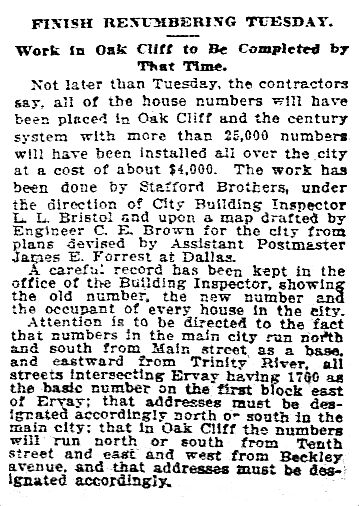

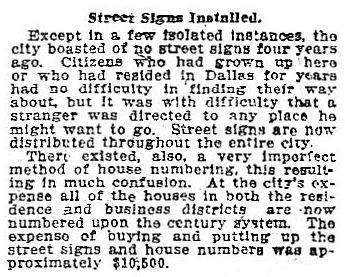

By the middle of January, 1911 the long-put-off task was completed, ending in Oak Cliff. The cost to the city of the “number placement” and the new street signs was $10,500.

(DMN, Jan. 15, 1911)

(DMN, Jan. 15, 1911)

The problem that had been moaned about for decades had been fixed, and a uniform system of street numbering had finally been put in place.

(DMN, Apr., 30, 1911)

(DMN, Apr., 30, 1911)

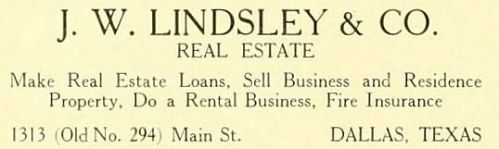

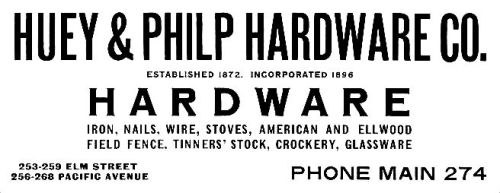

I can’t imagine how much of a headache and how unbelievably confusing the whole process and aftermath must have been. Several businesses, concerned that their clientele might have a difficult time “finding” them, hedged their bets by including BOTH address — the old and the new — on their letterhead and in their ads. This two-address thing went on for quite a while with some businesses — in fact, leading real estate man J. W. Lindsley was so annoyed by this practice that he complained about it to the Morning News in 1916 (a full five years after the switch!). Even though, ahem, Lindsley was one of the few advertisers in the Blue Book Directory for 1912-14 who did that very thing:

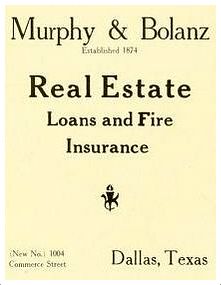

Unlike his competitor, Murphy & Bolanz, who had just the one (but still felt compelled to add the “new” to the address):

And that is today’s lesson on how Dallas finally bit the bullet and gave the entire city new addresses.

(And now I know that Neiman Marcus apparently IS the center of Dallas.)

**

UPDATE: HOW TO FIND THE OLD OR NEW ADDRESS. When I first wrote this, I’m not sure if I knew about the very handy resource Jim Wheat provided on his website: the 1911 Worley’s Dallas street directory, here. This is one way you can determine what the post-address-changeover was if you know the pre-1911 address (or vice-versa): find the street name and click on it. You’ll find two columns: one showing the “new” address, and the other the “old” address. (These aren’t always exact, but it at least gets you in the right block number to investigate further.) If you don’t know a specific address, you can make an educated guess according to the cross-streets. Thank you, Jim Wheat!

***

Photo of Young St. sign from Flickr, here. It’s great.

All newspaper articles from The Dallas Morning News.

The two real estate ads from The Standard Blue Book of Texas, 1912-14, Dallas Edition (Dallas: A. J. Peeler and Company, n.d.).

Slightly fuzzy Ervay-Main sign from Google Street View.

An early article about this issue, “Street Numbering, A Neglected Matter to Receive Attention Soon” (Dallas Daily Times-Herald, Nov. 22, 1889) can be found here.

And if you’re interested in just what goes into tackling a problem like this in modern times, hie yourself over to “Street-Naming and Property-Numbering Systems” by Margaret A. Corwin (American Planning Assn., ca. 1976). Read the entire report here, in a PDF. I’m nothing if not thorough.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

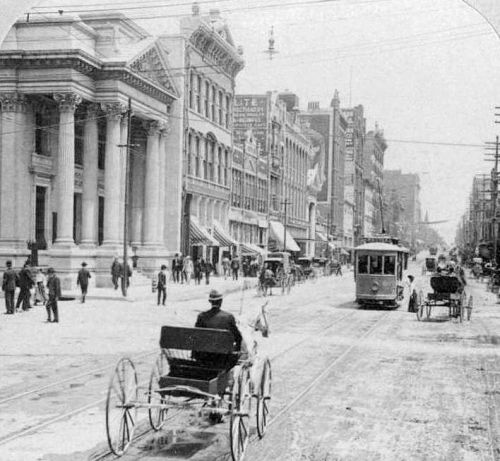

Elm St. at N. Lamar, looking east (click for much larger image)

Elm St. at N. Lamar, looking east (click for much larger image)

DMN, Jan. 1, 1909

DMN, Jan. 1, 1909

DMN, Aug. 11, 1914

DMN, Aug. 11, 1914

1890

1890

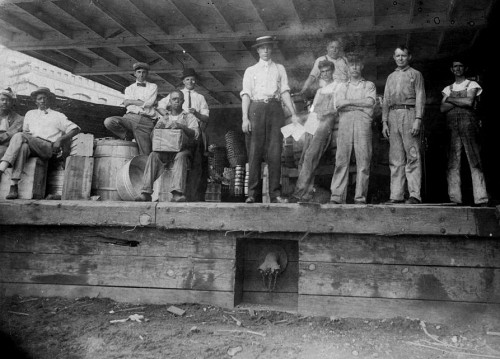

ca. 1910-15

ca. 1910-15 Mrs. Morrill’s house at Ross & Harwood, 1894

Mrs. Morrill’s house at Ross & Harwood, 1894 The Morrill house — next stop: demolition, 1920

The Morrill house — next stop: demolition, 1920

Photo by Silver Lighthouse/Flickr

Photo by Silver Lighthouse/Flickr

(DMN, Dec. 7, 1907)

(DMN, Dec. 7, 1907) (DMN, Dec. 17, 1909)

(DMN, Dec. 17, 1909) (DMN, Oct. 1, 1910)

(DMN, Oct. 1, 1910) (DMN, Jan. 15, 1911)

(DMN, Jan. 15, 1911) (DMN, Apr., 30, 1911)

(DMN, Apr., 30, 1911)