Flashback : Dallas

Category: 1900s

April 10, 2014

Oriental Oil Company: Fill ‘er Up Right There at the Curb

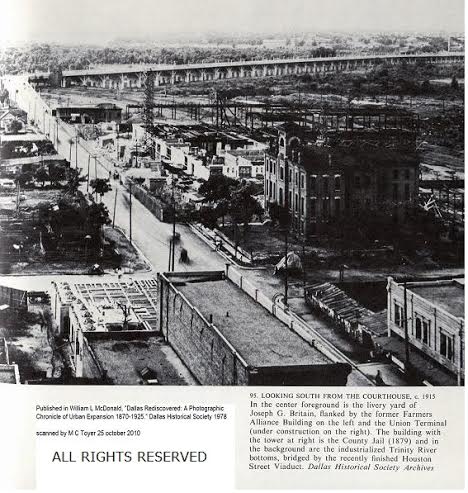

An Oriental Oil Co. competitor, at 1805 Commerce

An Oriental Oil Co. competitor, at 1805 Commerce

by Paula Bosse

I cropped this detail from a much larger view of Commerce Street because this incidental, everyday moment caught my attention. Was that man filling his automobile with gasoline? Was that square, boxy, hip-high thing full of gas, right there at the curb of one of the city’s busiest streets? The sign above the pump reads “PENNSYLVANIA AUTO OIL GASOLINE SUPPLY STATION.” I looked into it, and now I know more about early gas pumps and stations than I ever thought I would.

In the very early days of automobiles, one would have to seek out a supplier of gasoline (such as a hardware store or even a drugstore) where you would buy a gallon or two and carry it home with you in a bucket or something and then carefully pour it into your car’s gas tank using a trusty funnel. After a few years of this inconvenient way to gas up, these curbside pumps began to pop up in larger cities. The pump seen above was at 1805 Commerce St. and belonged to the Pennsylvania Oil Company. It opened in early 1912. That got me to wondering about other such fueling stations, and it seems the first in Dallas may have belonged to the Oriental Oil Company, just down the street from the one seen above, at 1611 Commerce. Here is a fuzzy image of it, from the same, larger photo the detail above was taken from. (Click for larger image.)

Could this photo have been taken there? It was listed on eBay merely as “Oriental Oil Company, Dallas, 1910-1920.”

Oriental Oil’s first “auto station” opened in February, 1911, where “facilities have been arranged so as to fill the cars along the sidewalk.”

(Dallas Morning News, Feb. 26, 1911)

(Dallas Morning News, Feb. 26, 1911)

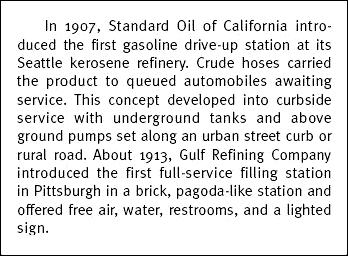

Drive-up “stations” had begun to appear a few years before, on the West Coast.

(Texas Dept. of Transportation, 2003)

(Texas Dept. of Transportation, 2003)

In a 1924 Dallas Morning News article (see below), the pump seen in the above photos was described thusly:

Dallas’ first gas filling station had a one-gallon blind pump on the curb which was then thought to be the last word in equipment. Now if a filling station is not equipped with a visible five-gallon pump it is thought to be behind the times and the gas now sold must be water white, when in the old days it was most any color.

This, I think, is what the Oriental and Pennsylvania rolling tanks looked like — the make and model may be different, but I think the general design is the same:

When it was empty, it would be rolled away to be re-filled. I’m not sure about the payment system. Coupon books are mentioned in one of the ads, but I don’t know how (or with whom) one would redeem them as these pumps appear to be self-serve. Perhaps there was a slot for coins/coupons, and everyone worked on the honor system.

It seems that its placement would cause a lot of congestion on a major street like Commerce (which at the time was still shared with skittish horses), but Commerce was also a hotbed of automobile dealerships (Studebaker, Stutz, and Pierce-Arrow dealerships, for example, were within a couple of blocks of the Oriental and Pennsylvania filling stations).

The Oriental Oil Company — a forgotten, early oil company — had an interesting history. The Dallas-based company began business in 1903, starting their company “in a barn in the rear of the Loudermilk undertaking establishment.”

(Southern-Mercury, Dec. 31, 1903)

(Southern-Mercury, Dec. 31, 1903)

They were a fast-growing oil company (“an independent concern which in spite of the strong opposition of the oil trust is now enjoying permanent and growing prosperity” – Greater Dallas Illustrated, 1908), and they were one of the first to open a refinery in Texas (they eventually had two refineries in West Dallas). The company’s primary concern in its early years was the manufacture of various oils and greases for industrial use.

Oriental Oil Company Factory, corner of Corinth St. and Santa Fe tracks, circa 1908

Oriental Oil Company Factory, corner of Corinth St. and Santa Fe tracks, circa 1908

In 1911, understanding just how profitable the new world of retail gasoline sales could be, they installed their first pump at the curb of 1611 Commerce St., near Ervay (“right behind the Owl Drug Store”). A 1924 Dallas Morning News account of the company (see below) states that this was the first gas pump … not only in Dallas … but in the entire state of Texas. I’m not sure if that’s true, but the Smith Brothers who ran Oriental Oil were certainly go-getters — the Smiths were grandsons of Col. B. F. Terry, organizer of the famed Terry’s Texas Rangers, and one of the brothers, Frank, was an early mayor of Highland Park and a three-term president of the Dallas Chamber of Commerce.

Shortly after opening their first pump on Commerce, demand was such that a second pump was soon opened at 211 Lane St. (a mere half a block away!). The DMN reported on Oct. 19, 1911 that a competitor — Consumers’ Oil and Auto Company — was going to be right across the street: “Permission was given to the Consumers’ Oil and Auto Company to place a gasoline tank under the sidewalk at 214 Lane street.” And in March 1912 the Pennsylvania Oil Company was installing ITS underground tank for the pump seen in the photo at the top — again, less than a block away. And in 1916 Oriental opened its splashy new “‘Hurry Back’ Auto Station” right across the street from where that Pennsylvania tank had been. (That Commerce-Ervay area was certainly an early gas station hotbed!)

Newspaper reports also cite claims made by the company that the station mentioned in the ad above — at Commerce and Prather — was the first drive-in gas station in the United States. I’m sure this was good truth-stretching PR for Oriental more than anything, because this claim was not true (Seattle and Pittsburgh seem to be battling each other for that honor). It might not have been the first, but when this “auto station” opened in 1916 (assuming it was “new” as this ad states), it was still pretty early in the history of the drive-in filling station. Also, by 1916, “Hurry Back” had become the company’s slogan as well as the name of its gasoline.

(Jewish Monitor, 1920; detail)

(Jewish Monitor, 1920; detail)

I love these ads!

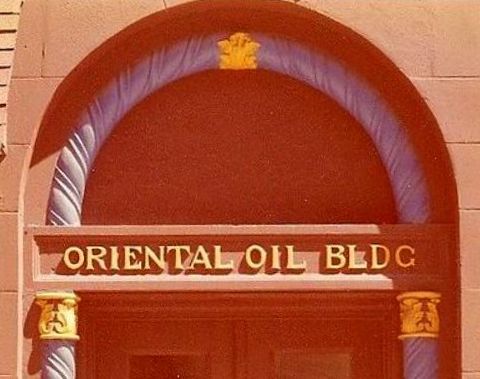

By 1927, the company boasted at least 18 filling stations, two refineries, and branches in Fort Worth and San Antonio. In 1927 they had moved into new offices in the “Oriental Building” at the nexus of Live Oak, St. Paul, and Pacific. A newspaper report described the building as being “finished in Oriental colors with Oriental decorations and is marked at night by very attractive lighting” (DMN, May 1, 1927).

The Oriental Oil Company declared bankruptcy in 1934, selling off their property, refineries, and their name. No more Oroco gas. A lot of companies went bust during the Great Depression, but I’m not sure what precipitated Oriental Oil’s bankruptcy. Actually, I’m surprised by how little information about the Oriental Oil Company I’ve been able to find. Afterall, it and its “Hurry Back” gasoline played a major role in getting the residents of Dallas off their horses and behind the wheel, a major cultural and economic shift that changed the city forever. And it all started at that weird little curbside gas pump on Commerce Street.

***

Sources & Notes

The first two images are details of a photograph by Jno. J. Johnson (“New Skyline from YMCA”), 1912/1913, from the DeGolyer Library, Central University Libraries, Southern Methodist University, viewable here.

Snippet of text from A Field Guide to Gas Stations of Texas by Dwayne Jones (Texas Department of Transportation, 2003).

Illustration of the two 1913 Tokheim portable gas pumps from An Illustrated Guide to Gas Pumps, Identification and Price Guide, 2nd Edition by John H. Sim (Iola, WI: Krause Publications, 2008).

Drawing of the Oriental Oil Company Factory from Greater Dallas Illustrated (Dallas: American Illustrating Co., 1908 — reprinted by Friends of the Dallas Public Library in 1992).

All ads and articles, unless otherwise noted, from The Dallas Morning News.

Color photo of the pink, purple, and gold Oriental Oil Bldg. is a detail from a photo taken around 1977, on Flickr, here.

For an interesting (and mostly accurate) mini-history of the Oriental Oil Company, then in its 20th year of operation, see the Dallas Morning News article “First Dallas Filling Station on Commerce Had One-Gallon Pump” (June 22, 1924).

Some nifty info on early gas stations (yes, really) here.

More info with some really great illustrations and photos here.

Another surprisingly fun and informative article is here.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

March 25, 2014

City Park Skating Rink — 1906

Don’t miss the “artistic skating” exhibition…

Don’t miss the “artistic skating” exhibition…

by Paula Bosse

CITY PARK RINK

Morning Session for Beginners.Special Attraction for Friday and Saturday

G. S. Monohan, champion fancy and trick skater of the Pacific Coast.

A wonderful exhibition of artistic skating Friday and Saturday afternoons and nights at 4 and 9 o’clock.

The admission fee of 15¢ will be charged all spectators and skaters for these four performances.

Tickets at Kramer’s Cigar Store.

***

Sources & Notes

Ad from the Dallas Morning News, March 14, 1906.

An article by Michael V. Hazel about the short-lived Old City Rink is here. (Legacies has covered absolutely EVERYTHING!)

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

March 25, 2014

City Hospital, a Pump Station, and the County Jail — 1894

Hospital, pump house, jail (click for larger image)

Hospital, pump house, jail (click for larger image)

by Paula Bosse

From 1894, an odd grouping of buildings: the City Hospital, a Dallas Waterworks Pumping House, and the Dallas County Jail. From a distance of 120 years, they’re all rather pleasant-looking, a word that would never be used to describe their 21st-century institutional counterparts. I wondered how many of the buildings had made it to the 20th century. Happily, they all did.

City Hospital opened in May of 1894 at Maple and Oak Lawn (it later became known as Parkland Hospital, the name coming from the 17 acres of land it occupied that had originally been planned as a city park). Here it is in about 1903, as a patient arrives in a horse-drawn ambulance. This wooden building was replaced in 1913 by the brick building that — yay! — still stands (in amongst its recent expansion and expansion and expansion by real estate mogul Crow the younger).

I looked all over for a later photograph of the “pumping station” but was unable to find a definite photo. I knew that it was built after the original pump house at Browder’s/Browder Springs in City Park and before the one now housing the Sammons Center for the Arts and the one at White Rock Lake. I think it might be this one, the Turtle Creek station, shown above during the devastating 1908 flood. If this is the same pump station, it looks as if there was quite a bit of expansion to this structure, too.

Dallas Morning News, Feb. 4, 1914

Dallas Morning News, Feb. 4, 1914

The building that changed the most from the pristine structure in the original 1894 photo was the Dallas County Jail, which was located at Houston and Jackson streets. Built in 1881, it was 13 years old in the original photograph. By the time it was 33 years old, it was almost unrecognizable, as can be seen (…sort of) in this photo, even with the horrible resolution. The jail had to keep expanding to keep up with demand and became a hulking mess. In the first decade of the century, reports began to appear in the newspapers of the deplorable conditions of the old jail and demands were made to improve conditions for prisoners. A new jail was built and the old one was auctioned off to the the Union Terminal Company which demolished the building in 1916, as the finishing touches were put on its Union Station, mere steps away from the former jail.

UPDATE: Thanks to reader M.C. Toyer, I have a couple of really great photos of the Old County Jail!

I’m not sure of the date of the one above, but the one below (such a great photo!) is dated 1915, the year the Old County Jail was finally emptied of its inmates, and a year before it was demolished.

Thanks for the great photos, MC!

***

Original photograph of the three buildings is by Clifton Church and appeared in his wonderful book Dallas, Texas Through a Camera (Dallas, 1894).

The photo of the ambulance in front of City Hospital is from the UT Southwestern Archives, with another photo of the same period here. A collection of newspaper articles on the hospital’s early history is here. An article on the City Hospital that pre-dated this one, with some harrowing descriptions of medical care in Dallas in 1875 is here.

The flooded Turtle Creek pump station is from the Dallas Municipal Archives. Other photos of this station can be seen here.

Bottom two photos of the Old County Jail sources are as captioned.

For more photos on the Dallas Waterworks/Turtle Creek Pump Station/Water Filtration Plant, see a later post of mine, here.

Click photos to enlarge.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

March 22, 2014

Nicholas J. Clayton’s Neo-Gothic Ursuline Academy

by Paula Bosse

Over the years, Dallas has been the site of dozens and dozens of beautiful educational campuses, almost none of which still stand — such as the long-gone Victorian-era Ursuline Academy, at St. Joseph and Live Oak streets (near the current site of the Dallas Theological Seminary). The buildings, which began construction in 1882, were designed by the Catholic church’s favorite architect in Texas, Nicholas J. Clayton of Galveston. Such a beautiful building in Dallas? It must be demolished!

Six Ursuline Sisters, sent to Dallas from Galveston, established their academy in 1874 in this poorly insulated four-room building (which remained on the Ursuline grounds until its demolition in 1949). When they opened the school, under tremendous hardship, they had only seven students. But the school grew in size and reputation, and they were an academic fixture in East Dallas for 76 years. In 1950 the Sisters moved to their sprawling North Dallas location in Preston Hollow where it continues to be one of the state’s top girls’ prep schools. After 140 years of educating young women, Ursuline Academy is the oldest continuously operating school in the city of Dallas.

Construction took a long time. (ca. 1894)

Construction took a long time. (ca. 1894)

When Latin cost extra. (1894) (Click for larger image.)

When Latin cost extra. (1894) (Click for larger image.)

It even had a white picket fence. (ca. 1906)

It even had a white picket fence. (ca. 1906)

After a year and a half on the market, the land was sold in 1949 for approximately $500,000 to Beard & Stone Electric Company (a company that sold and serviced automotive electric equipment). The property was bounded by Live Oak, Haskell, Bryan, and St. Joseph — acreage that would certainly go for a lot more these days (according to the handy Inflation Calculator, half a million dollars in 1949 would be the equivalent in today’s money of about five million dollars). A small cemetery was on the grounds, in which the academy’s first chaplain and “more than 40 members of the Ursuline order” had been buried. I’m not sure how these things are done, but the cemetery was moved.

From a November, 1949 Dallas Morning News article on the vacated buildings’ demolition:

A workman applied a crowbar to a high window casing of the old convent and remarked: “I sure hate to wreck this one. It’s like disposing of an old friend. My father was just a kid when this building was built in 1883.” (DMN, Nov. 13, 1949)

And one of East Dallas’ oldest and most spectacular landmarks was gone forever. Looking at these photographs, it’s hard to believe it ever existed at all.

*

Where was it? In Old East Dallas, bounded by Live Oak, Haskell, Bryan, and St. Joseph. See the scale of the property in the 1922 Sanborn map, here (once there, click for full-size map). Want to know what the same view as above looks like today? If you must, click here.

***

Sources & Notes

Photo of the school’s first building is from the Ursuline Academy of Dallas website here. A short description of the early days of hardship faced by the Sisters upon their arrival in Dallas is here.

The photograph, mid-construction, is by Clifton Church, from his book Dallas, Texas Through a Camera (Dallas, 1894).

1894 ad is from The Souvenir Guide of Dallas (Dallas, 1894).

1912 text is from an article by Lewis N. Hale on Texas schools which appeared in Texas Magazine (Houston, 1912).

Aerial photograph from the George W. Cook Dallas/Texas Image Collection, DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University, here. Bottom image also from the Cook Collection, here.

Examples of buildings designed by Nicholas J. Clayton can be seen here (be still my heart!).

DMN quote from the article “Crews Begin Wrecking Old Ursuline Academy” by William H. Smith (DMN, Nov. 13, 1949).

Another great photo of the building is in another Flashback Dallas post — “On the Grounds of the Ursuline Academy and Convent” — here.

Many of the images are larger when clicked.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

March 19, 2014

Celery Cola: “It Picks You Up!” — 1909

by Paula Bosse

When you think of Dallas and soft drinks, you probably think Dr Pepper. But back in 1909, Dallas was the main office for the Western division for the Birmingham, Alabama fizzy drink Celery Cola (containing, one presumes, delicious celery-flavored syrup). Their offices were in the somewhat low-rent stretch of Exposition while rival Coca Cola was snugly housed at the cushy southeast corner of N. Akard and Ross.

Only a couple of weeks after an official state charter was granted to local aspiring soda tycoons W. A. Massie, E. O. Massie, and J. B. Green to start officially producing the elixir in Dallas, this ad — a bit on the defensive side — appeared in the Dallas Morning News (click to see larger image):

Not so much an ad as testimony. Ads are usually more like this:

As it turns out, Celery Cola ceased production in 1910 after repeated findings of the presence of cocaine and large amounts of caffeine by the Pure Food and Drug Administration. Let’s hope Messrs. Massie, Massie, and Green bounced back from their ill-advised investment. The owner of the Celery Cola Company certainly bounced back — he continued to create soft drinks such as — no kidding — “Koke” and “Dope.” Dallas is better off with Dr Pepper. The only whispered allegation that’s dogged them is prune juice — and that stuff is 100% legal.

Check out the related Flashback Dallas post “‘No Mice, No Flies, No Caffeine, No Cocaine’ — 1911.”

***

Sources & Notes

Top ad from a Celery Cola site here.

Third ad, with the word “its” misspelled (*sigh*) from the comments section of a Shorpy post here.

Best overview on the history of Celery Cola and its creator, James Mayfield, is here.

My favorite part of this story was reading the long list of Dallas-area “illegal” soft drinks (and other oft-tampered-with foodstuffs) in J. S. Abbott’s First Annual Report of the Dairy and Food Commissioner of Texas (Austin, 1908). The soft drink list begins on p. 46 after an interesting prologue here. Celery Cola was not alone! (And, if I’m reading this correctly, Messrs. Massie, Massie, and Green were fully aware of what was going on, having provided the food cops with cocaine-laced samples several months before they bought into the company.)

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

March 17, 2014

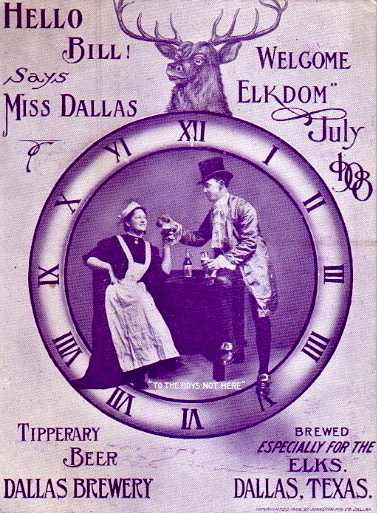

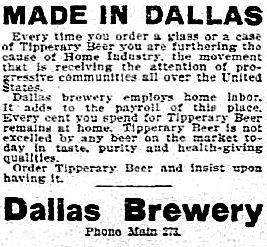

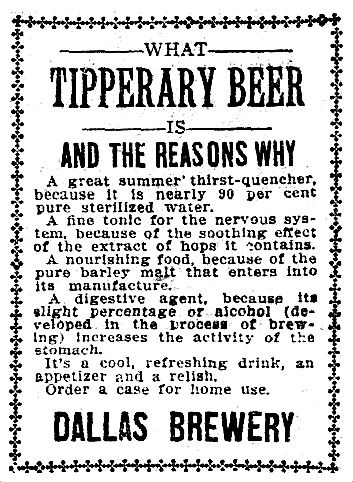

Tipperary Beer from the Dallas Brewery: “Insist Upon Having It”

1908

1908

By Paula Bosse

I’m pretty sure there’s no real Irish connection here — other than the name — but how could I pass this up on St. Patrick’s Day!

Dallas Morning News, July 18, 1906

Dallas Morning News, July 18, 1906

DMN, Sept. 1, 1907

DMN, Sept. 1, 1907

***

Sources & Notes

Top ad addressing the Elks’ conventioneers who were visiting Dallas in 1908 is from an Elks’ historical site, here.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

March 13, 2014

Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church: Germans on Swiss — ca. 1900

by Paula Bosse

The Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church was established in 1879 by German immigrants. In 1899 the congregation moved its church and school to the location seen in the photograph above, at 207 Swiss Avenue (street numbers have changed, but it was in the block between what is now Good-Latimer and Cantegral). The building remained in that location until at least 1921.

***

Photograph from the University of Texas at San Antonio, UTSA Libraries, Digital Collections.

For more on the history of the Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church in Dallas, see here.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

March 11, 2014

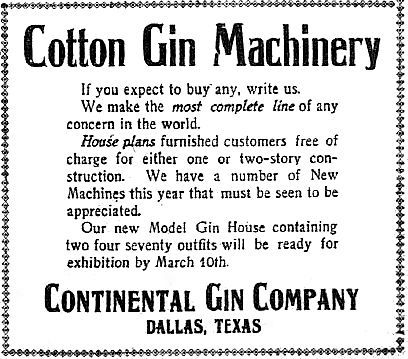

Munger’s Improved Continental Gin Company

A Dallas landmark… (click for larger image)

A Dallas landmark… (click for larger image)

by Paula Bosse

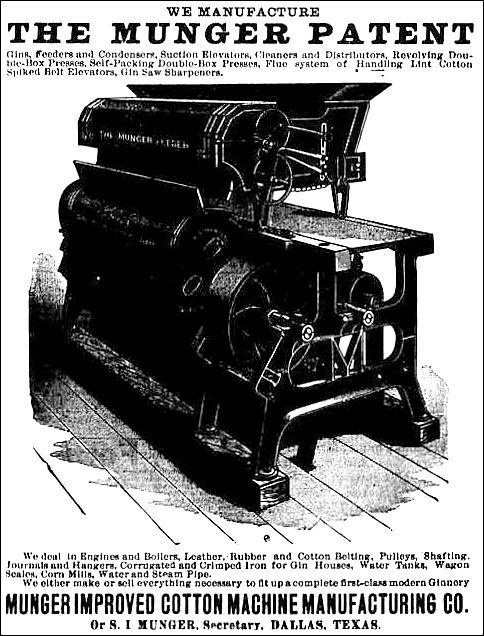

The Continental Gin Co. complex of buildings at Elm and Trunk is a Deep Ellum fixture which was successfully petitioned by the city in 1983 to be added to the National Register of Historic Places. No longer a manufacturing hub, it is now home to artists’ studios and residential lofts. The earliest of the buildings still standing were built in 1888 and the latest ones (the ones closer to Elm) were built in 1914. The company was incredibly successful, which was no surprise when one realizes that fully ONE-SIXTH of the world’s cotton grew within a 150-mile radius of Dallas at the time! It’s no wonder that Dallas was a hotbed of cotton gin manufacturing.

Munger Catalogue and Price List, 1895

Munger Catalogue and Price List, 1895

Robert S. Munger (yes, that Munger) patented several inventions that improved the cotton ginning process, and in 1888 he built a large manufacturing plant for his Munger Improved Cotton Machine Company. In 1900, after several extremely successful years, his company and several other companies that held important industry patents were absorbed by the Continental Gin Co. of Birmingham, Alabama, and, practically overnight, the Continental Gin Co. became the largest manufacturer of cotton gins in the United States. Munger retained a financial interest in the company, but he left the running of the business to his brother, S.I. Munger. R.S. Munger turned his creative talents to real estate and developed the exclusive Munger Place neighborhood. The Continental Gin Co. closed in 1962.

The Standard Blue Book of Texas, 1912-1914

The Standard Blue Book of Texas, 1912-1914

A few newspaper items regarding the Munger Improved Cotton Machine Company and the Continental Gin Company.

The Dallas Herald, Oct. 13, 1887

The Dallas Herald, Oct. 13, 1887

The Southern Mercury, May 30, 1889

The Southern Mercury, May 30, 1889

The Southern Mercury, July 28, 1892

The Southern Mercury, July 28, 1892

The Southern Mercury, April 13, 1893

The Southern Mercury, April 13, 1893

Change is imminent. (Dallas Morning News, July 26, 1900)

Change is imminent. (Dallas Morning News, July 26, 1900)

FIVE HUNDRED TONS! (DMN, Apri 20, 1901)

FIVE HUNDRED TONS! (DMN, Apri 20, 1901)

Worley’s Dallas Directory, 1909

Worley’s Dallas Directory, 1909

Photograph that accompanied the application to the National Register of Historic Places regarding the structures under consideration: 3301-3333 Elm St. and 212 & 232 Trunk Ave. (Landis Aerial Photography, 1980)

Photograph that accompanied the application to the National Register of Historic Places regarding the structures under consideration: 3301-3333 Elm St. and 212 & 232 Trunk Ave. (Landis Aerial Photography, 1980)

***

Sources & Notes

Handbook of Texas biography of Robert Sylvester Munger (1854-1923) is here.

The top image (which, by the way, took me FOREVER to find, is labeled as the Munger company, but the expansion would seem to indicate that this is the Continental Gin Company, after 1914. Whatever the case, it’s a great image!

That image and the aerial photograph of 1980 are included in the city’s application to have the complex included in the National Register of Historic Places, submitted in 1983. The detailed application — as a Texas Historical Commission PDF — can be accessed here.

The second image, of the early days of the Munger Improved Cotton Machine Company is from a bookseller’s online listing for Munger’s 13th Annual Catalogue and Price List (1895) — the item may still be available for a mere $435 and can be found here.

See an aerial view of what the area looks like today, via Google, here.

To see an incredible 1914 photograph of the buildings and the residential area to the north, see my post “The Continental Gin Complex — 1914,” here.

More on Robert S. Munger and more early company ads can be found in the post “R. S. Munger’s Cotton Gin Manufactory,” here.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

March 6, 2014

Remember the Alamo! …In Fair Park?

by Paula Bosse

Today, on the anniversary of the fall of the Alamo, I bring you news that Dallas has outdone San Antonio by having hosted two Alamos. TWO! Both in Fair Park. The first one was a gift to the city by G. B. Dealey and the Dallas Morning News — it stood stoically at the entrance to the fairgrounds from 1909 until 1935 — and the second one was a rebuilding of the first which was torn down to make way for the the splendor of the Art Deco Centennial extravaganza and lasted from 1936 until 1951. And here I’d never heard mention of Dallas having had ANY Alamos.

The idea came from Dallas Morning News executive George Bannerman Dealey. He sent architect J. P. Hubbell (of Hubbell & Greene) to San Antonio to meticulously photograph, sketch, and measure the original structure — this included making note of every stain, every crack, every instance of broken plaster, etc. — in order to reproduce an exact replica of the historical landmark (at half the size of the original). The Morning News offered to pay for and build the replica (the cost was estimated at $5,000) and asked only that it be placed in a primo location (at the entrance!), that it be open to the public during the day but be available to the DMN people to use for private/company functions after hours, and that the Park Board maintain the building and its landscaping. The Park Board jumped at the gift, and the news of our very own “little Alamo” was met with giddy anticipation. Even the rival Dallas Times Herald was swept up in the excitement and suggested a “Meet Me at the Alamo at the Dallas State Fair” slogan in an editorial.

San Antonio and the Daughters of the Republic of Texas (who managed and maintained the historic shrine) were not terribly amused by this, but The News (in the expected torrent of its own self-congratulatory publicity about its magnanimous gift “not to Dallas, but to the State”) humbly insisted that the much, much, MUCH smaller Alamo would only drum up steady tourism of people who wanted to see the real thing. San Antonio and the Daughters seemed to get over it eventually. Dealey had made a good point, though, when he said that only a very small percentage of Texans had been able to see the Alamo in person, and this was an excellent way to bring history alive for North Texans.

The replica was dedicated on the opening day of the fair in 1909, and curious crowds lined up to see the startlingly realistic reproduction of the building which Mayor S. J. Hay described as being “sacred to every patriotic citizen of the State.” The brand new Alamo (made to look old and worn and battle-scarred) was a hit. In fact, it seems to have been a very popular exhibit for the length of its stay — a total of 42 years. Other than being visited by thousands and thousands of fair-goers and families and schoolchildren, it was also used to house soldiers briefly during both World War I and World War II. It was visited by numerous people who claimed to be related to Alamo heroes like Crockett, Bowie, and Travis, and there were even a couple of instances of visits by 100-year-old men who said they had known Crockett and Bowie when they were children.

And, oddly, even Comanche Chief Quanah Parker stopped by to check the place out. I’ll end with his salient observations upon seeing the Alamo replica when visiting Dallas as a guest of the State Fair in 1909:

White men talk a great deal about their history. They don’t all play brave in making it. They don’t all care as much for getting it right as for getting it like they want it. Alamo fight was brave like Indians fight, don’t care for safety and for life. This Alamo house brings back to me thought of the ‘Dobe Walls’ fight a long time ago. It must make Texas people feel good to look at this and think of what it stands for. It was a fine thing for The News to put it here. (DMN, Oct. 27, 1909)

*

Above, opening day crowds. “Scene in front of the Replica of the Alamo Chapel During the Ceremony of Presentation.” Photo by Henry Clogenson. (DMN, Oct. 17, 1909)

Above, opening day crowds. “Scene in front of the Replica of the Alamo Chapel During the Ceremony of Presentation.” Photo by Henry Clogenson. (DMN, Oct. 17, 1909)

Dallas’ second Alamo (which made its debut at the Texas Centennial in 1936) no longer had its primo location at the entrance to Fair Park, but it at least had a bit of room to breathe. As with the first replica, an architect was sent to San Antonio to bring back exact measurements — this time it was the incomparable George Dahl (if you’re not familiar with his work, you need to look him up). And this time, San Antonio and the Daughters of the Republic of Texas were not happy at ALL: there was a sternly worded petition from San Antonio to the governor and threats to legally force a halt to the construction. Guess they got over it. Again.

Dallas’ second Alamo (which made its debut at the Texas Centennial in 1936) no longer had its primo location at the entrance to Fair Park, but it at least had a bit of room to breathe. As with the first replica, an architect was sent to San Antonio to bring back exact measurements — this time it was the incomparable George Dahl (if you’re not familiar with his work, you need to look him up). And this time, San Antonio and the Daughters of the Republic of Texas were not happy at ALL: there was a sternly worded petition from San Antonio to the governor and threats to legally force a halt to the construction. Guess they got over it. Again.

But eventually, the Alamo fell. It was razed in August of 1951, after years of neglect. Stalwart Texas demolition workers must have blanched a bit at being informed that their job was to destroy the very symbol of Texas heroism and independence.

***

Top postcard from a page on the Watermelon Kid’s great Dallas history site, here.

Photo of the “brand new” Alamo in 1936 from the Ryerson & Burnham Archives, Art Institute of Chicago, here.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.