The Palace Theatre, Elm St., Deep Ellum, 1922 (click for larger image)

The Palace Theatre, Elm St., Deep Ellum, 1922 (click for larger image)

by Paula Bosse

In 1920, movie theaters — like most places in Dallas at the time — were segregated. If black customers were allowed at all in the downtown white vaudeville and movie houses, they had separate entrances and restricted seating areas (generally in the balcony). But Dallas’ African-American community had their own popular theaters, run by enterprising and energetic men who endlessly promoted their jam-packed and constantly-changing bills.

Judging by the amount of ad space purchased in the black-owned and operated Dallas Express, there were four main movie theaters catering to black Dallasites around 1920: the Grand Central Theatre, run by John Harris, the Mammoth Theatre, run by Joe Trammell, the Palace Theatre, run initially by Felix Moore, and the High School Theatre, run by Herbert Batts; the first three of these houses were in Deep Ellum, the last one was in what was then called “North Dallas.’ The theaters played both “white” films and films with “all-Colored casts.” The advertising for these theaters is great — far more ad space was available in the tiny Express to publicize the movies, the popular but now-forgotten Silent Film stars of the era, and the proprietors themselves than was available to the theaters on the other end of Elm Street in the much larger, white-owned News, Journal, or Times Herald. Sometimes it’s good being the big fish in the little pond — absolutely everybody knows who you are.

*

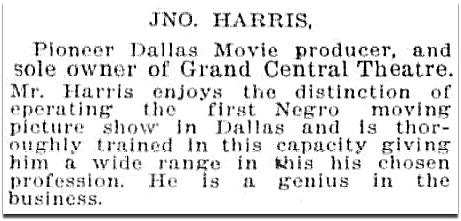

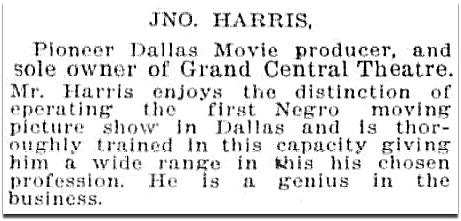

The Grand Central Theatre was at 405-407 N. Central Ave. (which later became Central Expressway), between Swiss and Live Oak on the outer northern edge of Deep Ellum. John Harris, the owner, put himself in practically all of his ads. He included this autobiographical sketch in one of them:

Dallas Express, May 28, 1921

Dallas Express, May 28, 1921

I’m not sure if he operated “the first Negro moving picture show in Dallas,” but I wouldn’t doubt it — the man was a dynamo who possessed not only a bold self-confidence, but he also seems to have had an unlimited promotional budget. UPDATE: The first appearance of a theatrical enterprise by John Harris shows up in the 1913 city directory (directories generally collected their information the previous year, so he was probably in business in 1912). Harris is listed under the “Amusements” section at the same address as the Grand Central Theatre, a name which came later. The same 1913 directory also lists the Star Theatre, which later became the Palace (see below). These are the only two theatres designated as “colored.” It’s unclear whether the theaters hosted live performances or showed movies. Or both.

The Grand Central advertised relentlessly. (Click ads to see larger images.)

Dec. 4, 1920

Dec. 4, 1920

May 14, 1921

May 14, 1921

Aug. 6, 1921

Aug. 6, 1921

Below, an ad showing one of the offerings to be a Ben Roy Motion Picture Corp. movie called “My Baby” which was “made in Dallas, featuring William Lee and All Colored Cast.”

May 27, 1922

May 27, 1922

Harris was connected with the legendary black filmmaker Oscar Micheaux. Not only did he regularly run his films, but he also seems to have been working as a booker, promoter, and distributor of Micheaux’s films and ran the Micheaux Film Productions branch office out of the Grand Central. “Colored Pictures are Money-Getters.”

May 14, 1921

May 14, 1921

One ad that caught my attention was this one, for a locally-shot film called “Colored Dallas.” I really, REALLY want to see this, but the possibility of an extremely minor, 95-year-old silent film having survived into the 21st century is slim.

Jan. 24, 1920

Jan. 24, 1920

*

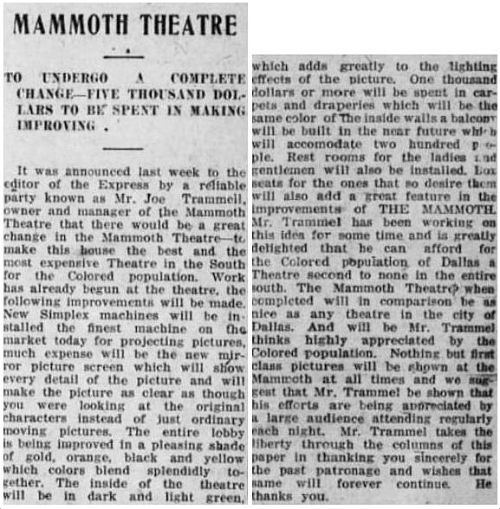

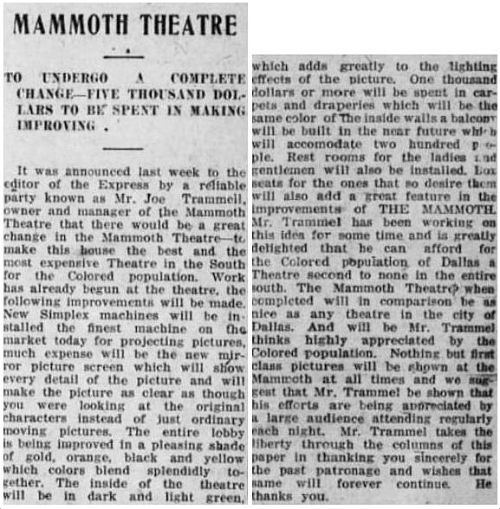

The Mammoth Theatre was located at 2401 Elm Street, between Central and Hawkins. It opened in late 1919 — the run-up to the opening was publicized in this Dallas Express item.

Nov. 22, 1919

Nov. 22, 1919

The Mammoth might not have advertised quite as much as the Grand Central did, but it frequently took out splashy full-page ads. Full-page! I bet that royally irked John Harris. Below, a Mammoth ad from 1920.

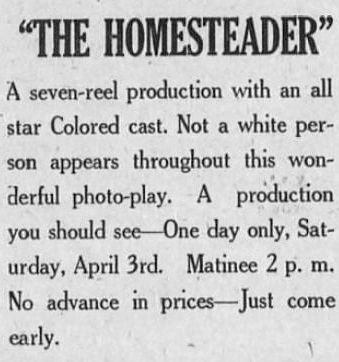

April 3, 1920

April 3, 1920

Two details from the above ad:

“Operated by Colored folks for Colored Folks.”

The owner, Joe Trammell, seems to have had an inexhaustible source of money for advertising — those frequent full-pagers (unusual for the time) must have cost a pretty penny. I couldn’t find much information about any of these men, but I stumbled across this photo of Trammell, tacked on to one of his … um … mammoth ads.

Feb. 12, 1921

Feb. 12, 1921

*

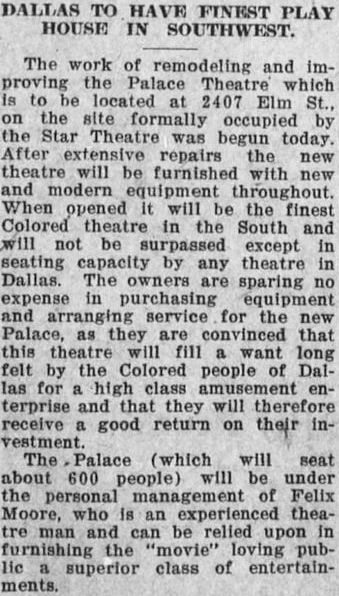

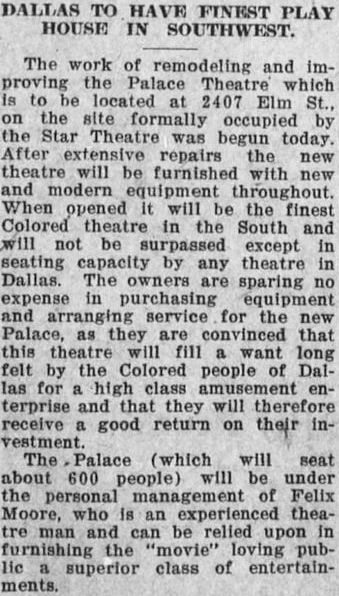

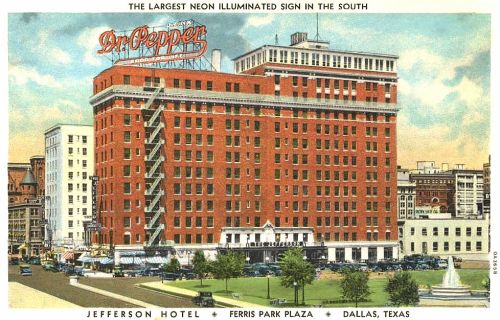

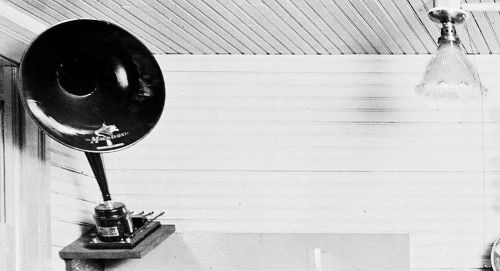

The Palace Theatre, seen in the photo at the top, was at 2407 Elm Street, just a couple of doors down from the Mammoth. (This Palace is not to be confused with the “white” Palace Theatre, the stalwart of Theater Row at the other end of Elm.) It opened in 1920 in the remodeled space formerly occupied by the Star Theatre,

March 6, 1920

March 6, 1920

May 8, 1920

May 8, 1920

*

Lastly, moving up to North Dallas, we find the High School Theatre, located at 3211 Cochran, between Central and N. Hall Street. The reason for its name was its close proximity to the Colored High School (the only high school for African-American students at the time — it would soon merge with and relocate to the new Booker T. Washington High School a short distance away). The following businesses were in this same block: the High School Cold Drink Stand, the High School Cafe, the High School Shine Parlor, and the High School Tailor Shop. Location, location, location.

March 15, 1919

March 15, 1919

My favorite High School Theatre ad is this one, touting a serial called “The Master Mystery” starring Houdini … one of the screen’s first appearances of a robot! (Check out a scene featuring both Houdini and the robot/automaton, here.)

March 15, 1919

March 15, 1919

*

The only one of these theaters still in business in 1930 was the Palace. by 1937, the Palace had become the Harlem Theatre.

***

Sources & Notes

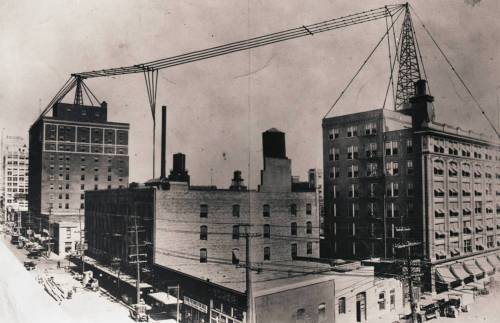

Top photo showing Elm Street and the Palace Theatre and the bottom two photos showing the Harlem Theatre are from the Texas/Dallas History & Archives Division, Dallas Public Library. The upsetting view of what that stretch of Elm looks like now can be seen on Google Street View, here. Below, side-by-side, 1922 and 2015 — Elm St. looking east to Deep Ellum, the Knights of Pythias temple in both images down the street on the left. Look what we’ve lost.

All ads and clippings from The Dallas Express, as noted. A few years’ worth of this important newspaper, which served Dallas’ African-American community, can be accessed here.

More on Oscar Micheaux, here.

Another Flashback Dallas post on a theater serving the black community is “Oak Cliff’s Star Theatre — 1945-1959.”

A 1919 map from UNT’s Portal to Texas History shows the location of the Grand Central Theatre (red square), the Mammoth (blue), and the Palace (yellow).

The High School Theatre — up in “North Dallas” (adjacent to present-day Uptown) — is seen on a different portion of the same map, below.

Most images are larger when clicked.

*

Copyright © 2015 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

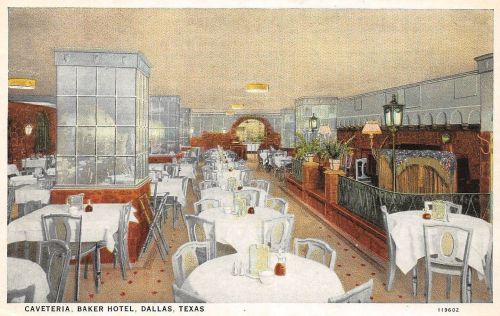

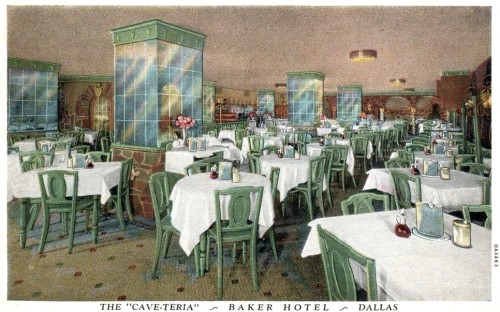

The finest in downtown basement dining (click for larger image)

The finest in downtown basement dining (click for larger image)

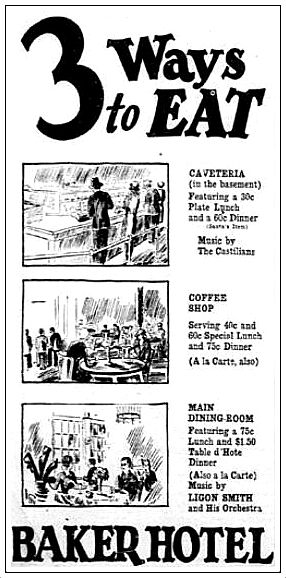

DMN, Feb. 1, 1931

DMN, Feb. 1, 1931 DMN, Feb. 15, 1932

DMN, Feb. 15, 1932 Corsicana Daily Sun, Mar. 16, 1932

Corsicana Daily Sun, Mar. 16, 1932

Dallas Express, May 28, 1921

Dallas Express, May 28, 1921

Feb. 12, 1921

Feb. 12, 1921 March 6, 1920

March 6, 1920

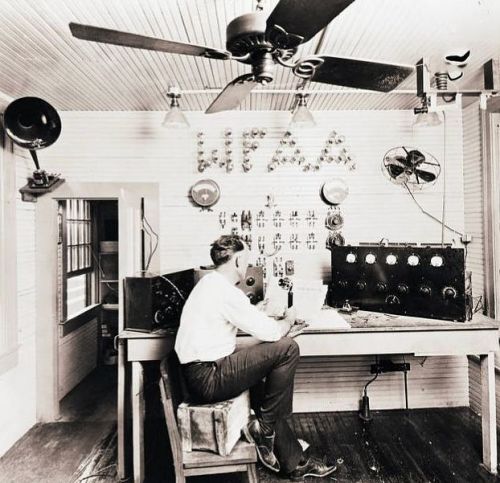

DMN, June 25, 1922

DMN, June 25, 1922

DMN, June 25, 1922

DMN, June 25, 1922 DMN, June 25, 1922

DMN, June 25, 1922