An unusual view of the smokestacks from 1939 — in color!

by Paula Bosse

I got to thinking about those two smokestacks that used to be such an important part of the Dallas skyline when I came across this rather forceful 1928 Dallas Power & Light Company ad:

(click for larger image)

“More than twenty thousand ways” to use electricity, “your tireless mechanical slave”! (To see a larger image of the ad’s illustrated inset, click here.)

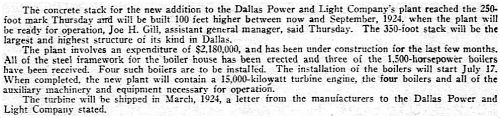

According to The Dallas Morning News, the Dallas Power & Light Company power plant had been in use at the location at “at the foot of Griffin Street … since 1890, with additions in 1905, in 1912 and in 1914. In 1922 work started on the most recent addition, which when completed will cost over $2,000,000, and will provide additional generating capacity of furnishing 20,000 kilowatts” (DMN, Oct. 14, 1923).

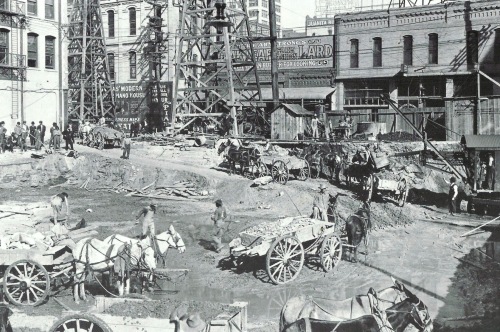

Construction on the new addition — including the first of the two new smokestacks — began in the summer of 1922.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, July 28, 1922

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, July 28, 1922

By the summer of 1923 the first smokestack was partially built.

DMN, July 13, 1923 (click for larger images)

DMN, July 13, 1923 (click for larger images)

The new addition was completed in 1924 (although improvements and construction were constantly ongoing). The new giant smokestack can be seen in this photo, alongside the old and new parts of the generating plant:

DMN, Oct. 12, 1924

DMN, Oct. 12, 1924

And, another view, this one with the 8-acre “spray pond” in the foreground:

DMN, Oct. 12, 1924

DMN, Oct. 12, 1924

In 1928 DP&L announced that it needed a further addition:

Another large chimney or smokestack, a new boiler room and other plant enlargements will be required in the North Dallas generation plant to house the new addition. (DMN, Oct. 20, 1928)

And in 1929 … voilà — the second smokestack!

1929

Those two smokestacks (which actually emitted steam rather than smoke) were almost as much a part of the iconic Dallas skyline as Pegasus. You’ll see them in any wide shot of the skyline taken between 1929 and the late 1990s, when the plant was demolished to make way for the American Airlines Center (the design of which actually is reminiscent of the building it replaced). You could see those smokestacks from miles away, and, even though they’ve been gone for more than 15 years, I still expect to see them standing there. RIP, smokestacks!

*

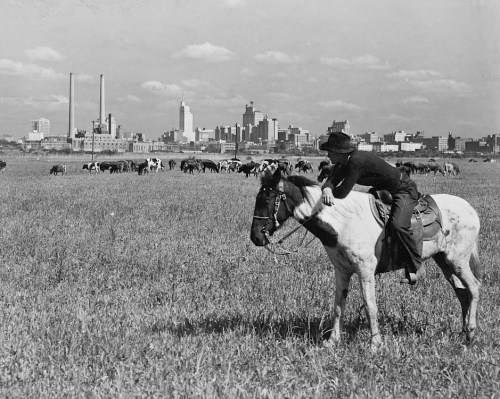

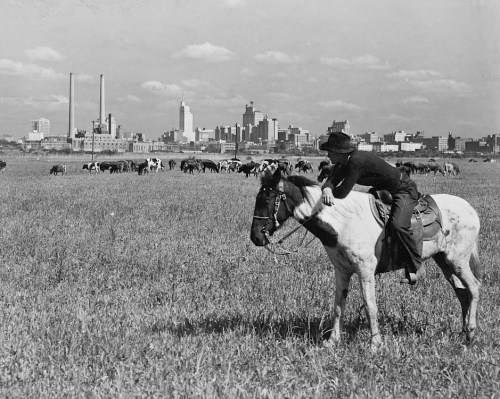

1930s, via DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

1930s, via DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University

Photo by William Langley, 1945 (with the twin stacks AND Pegasus)

Photo by William Langley, 1945 (with the twin stacks AND Pegasus)

via Squire Haskins Collection, University of Texas at Arlington

via Squire Haskins Collection, University of Texas at Arlington

Aerial photo by Lloyd M. Long, 1948 (detail)

Aerial photo by Lloyd M. Long, 1948 (detail)

***

Sources & Notes

Color image is a screengrab from the short 1939 color film of Dallas which you can watch in full, here.

Ad is from the 1928 Terrillian, the Terrill School yearbook.

William Langley photo of the cowboy on horseback is from the Library of Congress, used previously here.

Lloyd M. Long aerial photo is a detail of a photo cataloged as “Downtown Dallas — looking west,” from the Edwin J. Foscue Map Library, Central University Libraries, Southern Methodist University; the full photo and its details are accessible here.

For an unexpectedly enthusiastic essay about the design and cultural/aesthetic significance of the plant and its smokestacks, architecture critic David Dillon’s “Getting Up a Head of Steam: DP&L’s Power Station, Recalling an Urban Past, Is a Function of Triumph” (Dallas Morning News, Sept. 7, 1983) is well worth searching for in the Dallas Morning News archives. This is the first paragraph:

The Dallas Steam Electric Station on Stemmons is nearly a century old and for most of that time it has been a commanding presence on the downtown skyline, its soaring white smokestacks rivaling anything that modern skyscraper designers have come up with. In Pittsburgh or Detroit such a structure might pass unnoticed but in Dallas, never a factory town, it stands out as a romantic symbol of our earliest industrial aspirations.

(My favorite piece of trivia from Dillon’s article is the revelation that the “tapering white shafts and gold caps [were] touched up every few years by daredevil painters lowered from a helicopter…” (!)).

More about this plant (and how it lives on in the design of the American Airlines Center which now stands on the same land) can be found in the Flashback Dallas post “A New Turbine Power Station for Big D — 1907,” here.

As always, most images are larger when clicked. When in doubt … CLICK!

*

Copyright © 2015 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

Bleak campus, cool cars (click for larger image)

Bleak campus, cool cars (click for larger image)

FWST, Nov. 3, 1924

FWST, Nov. 3, 1924 FWST, Nov. 11, 1924

FWST, Nov. 11, 1924

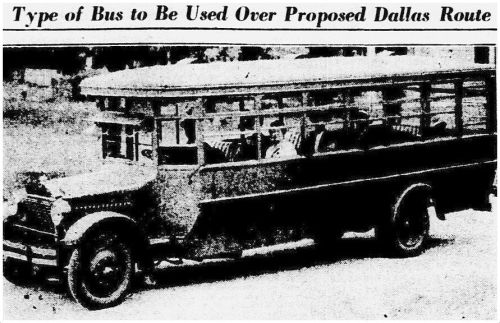

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, July 28, 1922

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, July 28, 1922

DMN, Oct. 12, 1924

DMN, Oct. 12, 1924