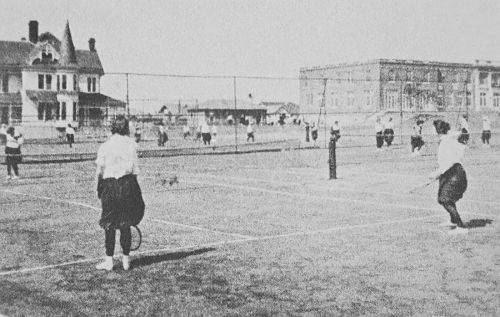

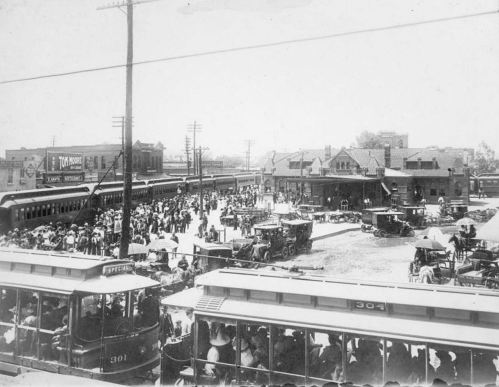

Hockaday campus, 1950 (UTA Libraries)

by Paula Bosse

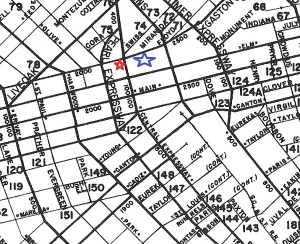

If you’ve driven down lower Greenville Avenue lately, you’re probably aware that the buildings that most recently housed a retirement home at the northwest corner of Belmont and Greenville were scheduled to be been torn down. When I drove past that intersection a few weeks ago and saw the entire block leveled, I was shocked. It’s weird suddenly not seeing buildings you’ve seen your entire life. It got me to wondering what had been on that block before. I’d heard that Hockaday had occupied that block for several years, but even though I’d grown up not too far away, I’d only learned of that within the past few years. When I looked into this block’s history, the most surprising thing about it is that it has passed through so few owners’ hands over the past 140 or so years.

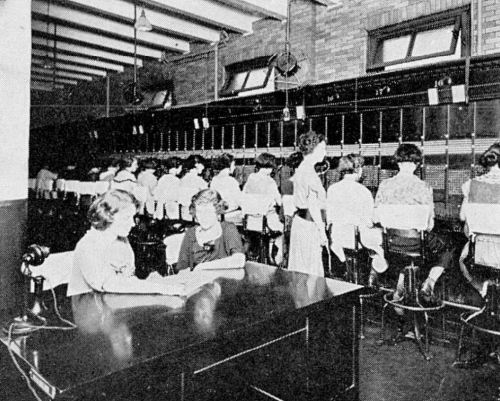

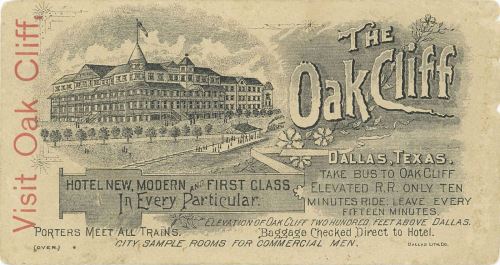

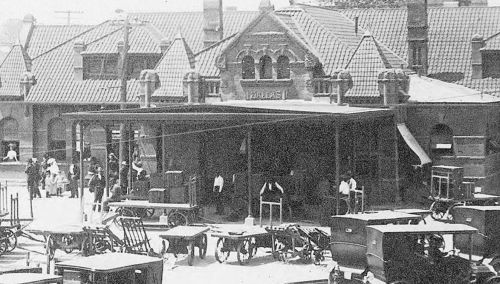

As far as I can tell, the first owner or this land was Walter Caruth (1826-1897), a pioneer merchant and farmer who arrived in this area in the 1840s (some sources say the 1850s), along with his brother, William. Over the years the brothers amassed an absolutely staggering amount of land — thousands and thousands of acres which stretched from about Inwood Road to White Rock Lake, and Ross Avenue up to Forest Lane. One of Walter Caruth’s tracts of land consisted of about 900 acres along the eastern edge of the city — this parcel of land included the 8 or 9 acres which is now the block bounded by Greenville, Belmont, Summit, and Richard, and it was where he built his country home (he also had a residence downtown). The magnificent Caruth house was called Bosque Bonita. Here is a picture of it, several years after the Caruths had moved out (the swimming pool was added later).

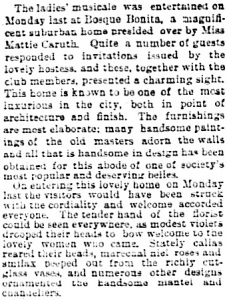

Most sources estimate that the house was built around 1885 (although a 1939 newspaper article stated that one of Walter’s children was born in this house in 1876…), but it wasn’t until 1890 that it began to be mentioned in the society pages, most often as the site of lavish parties. (Click pictures and articles to see larger images.)

Dallas Morning News, Feb. 3, 1890

Dallas Morning News, Feb. 3, 1890

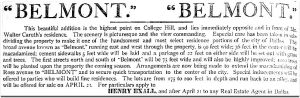

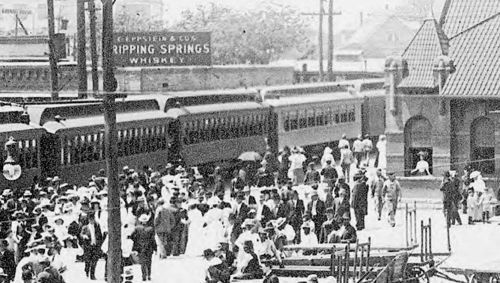

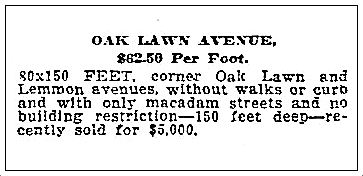

At the time, the Caruth house was one of the few buildings in this area — and it was surrounded by endless acres of corn and cotton crops. It wasn’t long, though, before Dallas development was on the march eastward and northward. This ad, for the new Belmont Addition, appeared in April of 1890, and it mentioned the Caruth place as a distinguished neighboring landmark.

DMN, April 16, 1890

By the turn of the century — after Caruth’s death in 1897 — it was inevitable that this part of town (which was not yet fully incorporated into the City of Dallas) would soon be dotted with homes and businesses.

DMN, Sept. 27, 1903

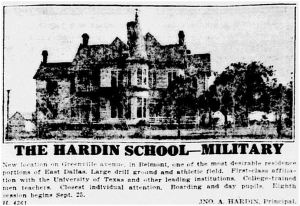

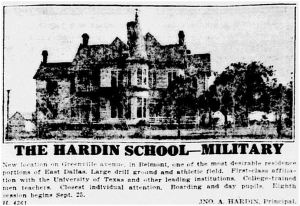

At one time the Caruth family owned land in and around Dallas which would be worth the equivalent of billions of dollars in today’s money. After Walter Caruth’s death, the Caruth family became embroiled in years of litigation, arguing over what land belonged to which part of the family. I‘m not sure when Walter Caruth’s land around his “farmhouse” began to be sold off, but by 1917, the Hardin School for Boys (established in 1910) moved into Bosque Bonita and set up shop. It operated at this location for two years. The Caruth house even appears in an ad.

DMN, July 15, 1917

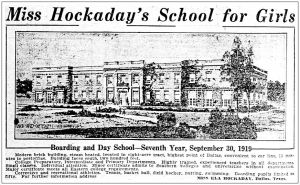

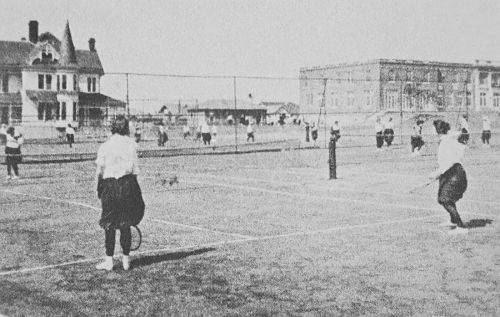

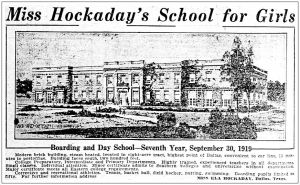

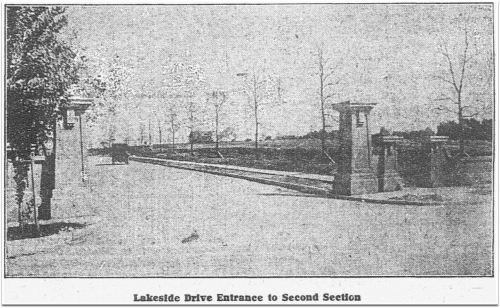

I’m not sure if the Hardin School owned the land or was merely leasing it and the house, but in 1919, Ela Hockaday announced that she had purchased the land and planned to move her school — Miss Hockaday’s School for Girls (est. 1913) — to this block and build on it a two-story brick school building, a swimming pool (seen in the photo above), tennis courts, basketball courts, hockey fields, and quarters for staff and girls from out of town who boarded.

DMN, May 11, 1919

DMN, May 11, 1919

DMN, July 6, 1919

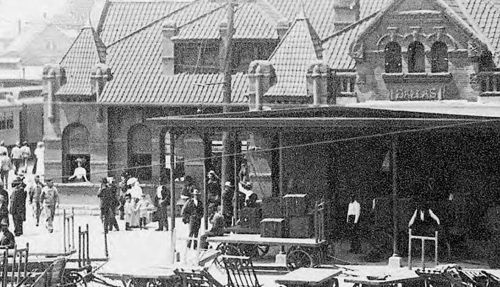

Ground was broken in July of 1919, and the first session at the new campus began on schedule in September. Below, the building under construction. Greenville Avenue is just out of frame to the right.

Photo: Hockaday 100

Photo: Hockaday 100

The most interesting thing I read about the Hockaday school occupying this block is that very soon after opening, the beautiful Caruth house was moved from its original location at the northwest corner of Belmont and Greenville. It was rolled on logs to the middle and back of the property. “Bosque Bonita” became “Trent House.” Former student (and later teacher) Genevieve Hudson remembered the moving of the house in an oral history contained in the book Reminiscences: A Glimpse of Old East Dallas:

You can see the new location of the house in the top aerial photo, and in this one:

Dallas Public Library

Another interesting little tidbit was mentioned in a 1947 Dallas Morning News article: Caruth’s old hitching post was still on the property — “on Greenville Avenue 100 feet north of the Belmont corner” (DMN, May 2, 1947). I’d love to have seen that.

After 42 years of sustained growth at the Greenville Avenue location (and five years after the passing of Miss Hockaday), the prestigious Hockaday School moved to its current location in North Dallas just after Thanksgiving, 1961. Suddenly, a large and very desirable tract of land between Vickery Place and the M Streets was available to be developed. Neighbors feared the worst: high-rise apartments.

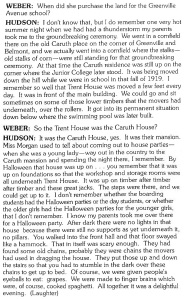

The developer proposed a “low-rise,” “semi-luxury” (?) group of four 5-story apartment buildings, each designed to accommodate specific tenants: one for swinging singles (“where the Patricia Stevens models live”), one for single or married adults, one for families with children, and one for “sedate and reserved adults.” It was to be called … “Hockaday Village.” The architect was A. Warren Morey, the man who went on to design the cool Holiday Inn on Central and, surprisingly, Texas Stadium.

Bosque Bonita — and all of the other school buildings — bit the dust in preparation for the apartment’s construction. Hockaday Village (…what would Miss Hockaday have thought of that name?) opened at the end of 1964.

Oct. 1964

Oct. 1964

March 1965

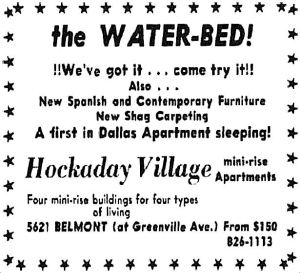

And then before you knew it, it was the ’70s, the era of waterbeds and shag carpeting. (Miss Hockaday would not have tolerated such tackiness, and I seriously doubt that Mr. Caruth would have ever understood why shag carpeting was something anyone would actually want.)

1971

Then, in 1973, the insistently hip ads stopped. In April, 1974 this appeared:

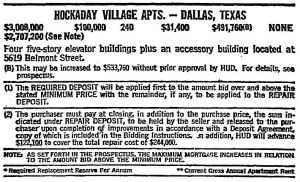

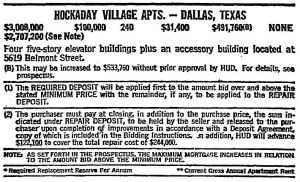

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, April 28, 1974

The apartments were being offered for public auction by the “Office of Property Disposition” of the Federal Housing Authority and HUD. Doesn’t sound good. So who bit and took the plunge? The First Baptist Church of Dallas, that’s who. The plan was to redevelop the existing apartments into a retirement community called The Criswell Towers, to be named after Dr. W. A. Criswell. But a mere three months later, the Baptists realized they had bitten off more than they could chew — the price to convert the property into a “home for the aged” would be “astronomical.” They let the building go and took a loss of $135,000. It went back on the auction block.

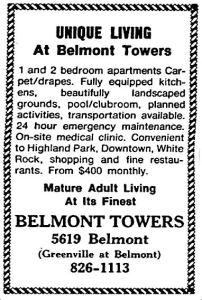

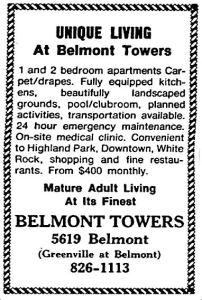

Two years later, in the summer of 1976 … the old Hockaday Village became Belmont Towers — and the new owners must have thought the Baptists’ idea was a good one, because Belmont Towers advertised itself as “mature adult living at its finest” — “perfect for retired or semi-retired individuals.”

April 1983

It was Belmont Towers for 20-or-so years. In 1998, the buildings were renovated and updated, and it re-opened as Vickery Towers, still a retirement home and assisted living facility. A couple of years ago it was announced that the buildings would be demolished and a new development would be constructed in its place. It took forever for the 52-year-old complex to finally be put out of its misery since that announcement. Those buildings had been there my entire life and, like I said, it was a shock to see nothing at all in that block a few weeks ago.

Photo: Danny Linn

Photo: Danny Linn

In the 140-or-so years since Walter Caruth acquired this land in the 1870s or 1880s, it has been occupied by Caruth’s grand house, a boys school, the Hockaday School, and four buildings which have been apartments and a retirement community. And that’s it. That’s pretty unusual for development-crazy Dallas. I’ll miss those familiar old buildings. I hope that whatever is coming to replace them won’t be too bad.

Bing Maps

***

Sources & Notes

The top aerial photograph is by Squire Haskins, taken on Feb. 27, 1950 — from the Squire Haskins Photography Inc. Collection, University of Texas at Arlington Libraries, Special Collections, accessible in a massive photo here (click the thumbnail). Greenville Avenue is the street running horizontally at the bottom. The Hockaday Junior College can be seen at the northwest corner of Belmont and Greenville — the original location of Bosque Bonita before it was rolled across the campus.

That fabulous photo of Bosque Bonita is from the book Dallas Rediscovered by William L. McDonald.

Photo of Hockaday girls playing tennis is from the book Reminiscences: A Glimpse of Old East Dallas.

Photo of girls on horseback … I’m not sure what the source of this photo is.

Photo of the block, post-razing is by Danny Linn who grew up in Vickery Place; used with permission. (Thanks, Danny!)

All other sources as noted.

In case you were confused, the Caruth Homeplace that most of us might know (which is just south of Northwest Highway and west of Central Expressway) was the home of Walter Caruth’s brother William — more on that Caruth house can be found here.

The Hockaday School can be seen on the 1922 Sanborn map here (that block is a trapezoid!).

More on the history of the Hockaday School can be found at the Hockaday 100 site; a page with many more photos is here. Read about the history of the school in the article “Miss Ela Builds a Home” by Patricia Conner Coggan in the Spring, 2002 issue of Legacies, here.

Additional information can be found in these Dallas Morning News articles:

- “Proposal to Change Hockaday Site to Apartment Zoning Opposed” (DMN, Oct. 29, 1961)

- “Retirement Home Plans Going Ahead” (regarding the purchase by the First Baptist Church of Dallas) (DMN, June 15, 1974)

- “Church Takes $135,000 Loss on Property” (DMN, Sept. 10, 1974)

*

If you made it all the way through this, thank you! I owe you a W. C. Fields “hearty handclasp.”

*

Copyright © 2016 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

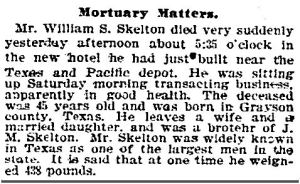

Dallas Morning News, Sept. 15, 1886

Dallas Morning News, Sept. 15, 1886 DMN, Sept. 30, 1888

DMN, Sept. 30, 1888