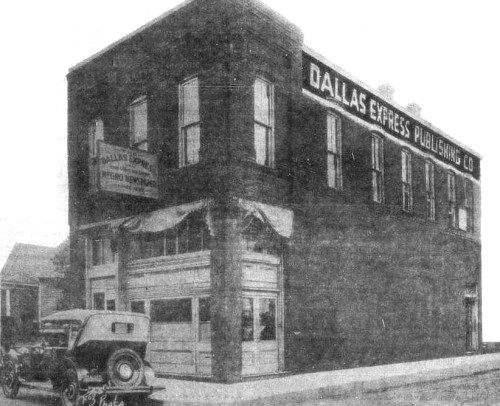

The Dallas Express — A Look Inside the Offices of the City’s Most Important Black Newspaper — 1924

2600 Swiss, home of The Dallas Express (click for larger image)

2600 Swiss, home of The Dallas Express (click for larger image)

by Paula Bosse

Without question, The Dallas Express (1892/3-1970) was the most important and most widely-read black-owned newspaper published for Dallas’ African-American community. In addition to stories of particular interest to its Dallas and Texas readership, it also covered national and international news, and in the Jim Crow era, when black Dallasites were rarely mentioned in white-owned newspapers except in crime reports, The Express reported on the people, the businesses, the churches, and the achievements of their large community. They also wrote about politics and issues of race and discrimination. One of the paper’s slogans was “A Champion of Justice, A Messenger of Hope.”

I’ve been interested in newspapers, journalism, and the actual physical process of printing newspapers for as long as I can remember, but until a couple of years ago, I was not aware of The Dallas Express, founded in 1892 by publisher/editor W. E. King. Discovering this paper and its stories about my hometown has been eye-opening. The Dallas Express is an important — and often overlooked — source of Dallas history. I love reading through issues of The Express because unlike white-owned papers of this period, it presents a realistic and human chronicle of the everyday lives of Dallas’ black men and women, something which was almost completely ignored by The Dallas Morning News and The Dallas Times Herald.

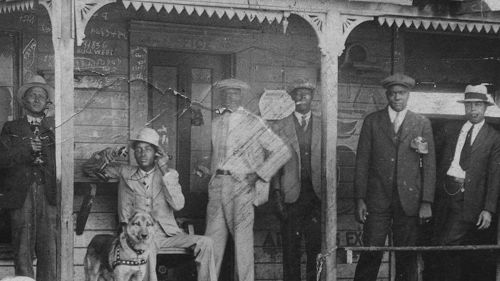

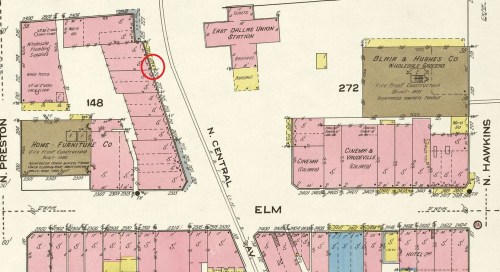

For many years, the offices of the Express were just north of Deep Ellum, at 2600 Swiss — at the corner of Good Street, about where Brad Oldham’s Traveling Man sculpture stands today. (I have a feeling the actual location was in the middle of what is now Good-Latimer. See the location on a 1921 Sanborn map here.) Happily, the Express printed a full-page ad for itself in the June 7, 1924 edition, so we can see what the Swiss Avenue building, its offices, and its production rooms looked like. These photos were taken by noted Dallas photographer Frank Rogers. (Apologies for the muddy quality of these photos — I’d love to see the crisp originals!)

*

These photos show the Dallas Express offices as they looked in 1924, when the newspaper had already been in business for 32 years. The exterior of the two-story building can be seen in the photo at the top — standing next to a private residence. (Click photos to see larger images.)

Below, president and business manger (and, later, owner), C. F. Starks:

The editor’s office (John W. Rice was the editor at this time and is, presumably, the man in the foreground):

The business office:

The composition room:

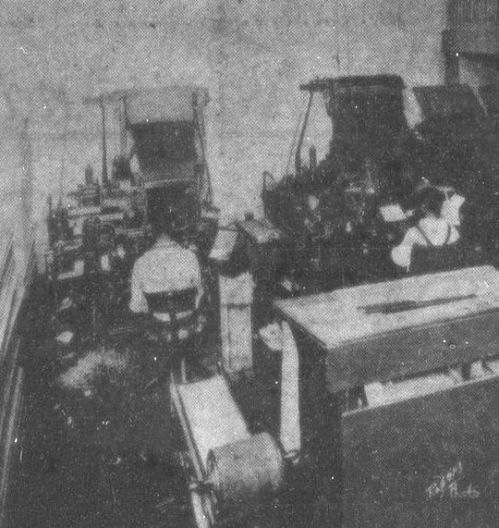

The linotype department (I have written about my fascination with linotype machines here):

And the press room:

The text from the ad (this special “Pythian Edition”of the paper was printed to coincide with the 40th annual meeting of the Knights of Pythias):

“YOUR Paper,” The 5th Largest of its Kind in America, Commends The Knights of Pythias Along With All of the Other Fraternities Represented Here for Their WONDERFUL PROGRESS.

THE EXPRESS believes that much of the splendid success which has come to the Fraternities of Texas, has come because of the fact that they have told the public “well and often” about the benefits which they offer and the advantages which they bring. And too, this paper takes a great deal of PRIDE in the thought that it has helped to bring this to pass because it is the medium in Texas best fitted to tell the world about the PROGRESS of the institution of our State.

These views of our force and the equipment at our plant explain why we can guarantee “Distinctive Service” and “Meritorious Printing” to every one of our customers.

The 20,000 copies in this special issue will go to every corner of America and to some foreign countries. No other journal of the Race in the Southwest does this.

The Dallas Express Pub. Co. Solicits Your Patronage not because it is a Negro institution but because it can guarantee to you the sort of service that you need. No job too small for the greatest consideration. No order too big for us to fill.

TEXAS’ OLDEST AND LARGEST NEGRO NEWSPAPER AND PRINTING PLANT

In Dallas Since 1892

2600 Swiss Avenue

*

The full-page ad:

Another photo of the printing room appeared in an Express ad which ran in the paper the following week:

***

Sources & Notes

Photos by Frank Rogers. Original prints might be in the Frank Rogers Collection at the Dallas Public Library, but nothing showed up when I searched the DPL database. Original crisp prints would be wonderful to see!

Photos appeared in the June 7, 1924 edition of The Dallas Express. The full newspaper can be found here. Only a few years’ worth of scanned issues of The Express are available on UNT’s Portal to Texas History site — mostly 1919-1924 — they can be accessed here.

Read about The Dallas Express at the Portal to Texas History, here; the Wikipedia entry is here.

*

Copyright © 2016 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

“Social chitchatterers” (Life, Dec. 6, 1927)

“Social chitchatterers” (Life, Dec. 6, 1927) (Life, Dec. 6, 1927)

(Life, Dec. 6, 1927)

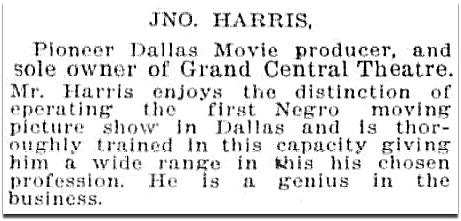

Dallas Express, May 28, 1921

Dallas Express, May 28, 1921

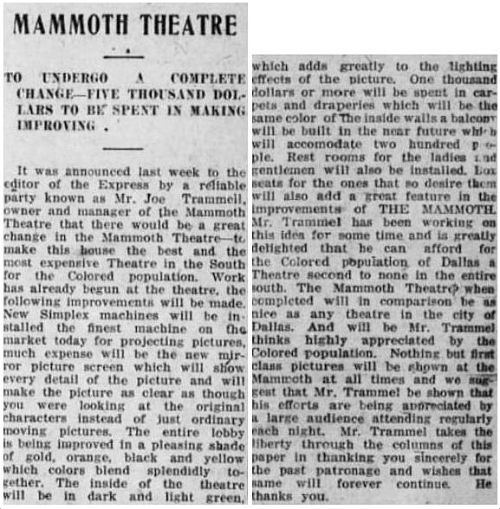

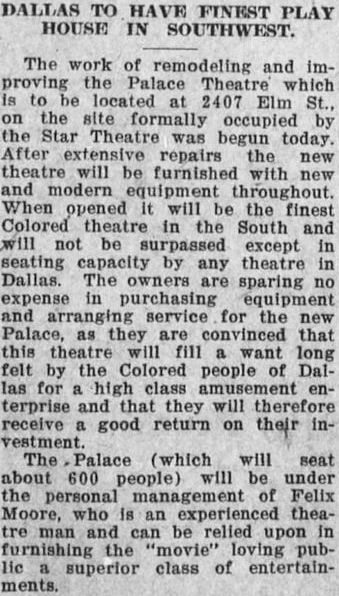

Feb. 12, 1921

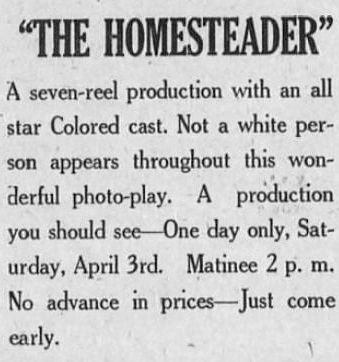

Feb. 12, 1921 March 6, 1920

March 6, 1920