“Artesian Well Gushes on the Courthouse Grounds”

“Artesian Well Gushes on the Courthouse Grounds”

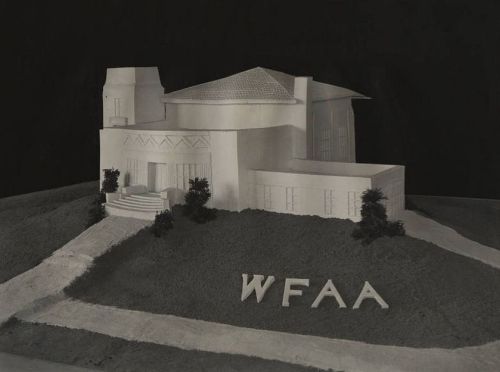

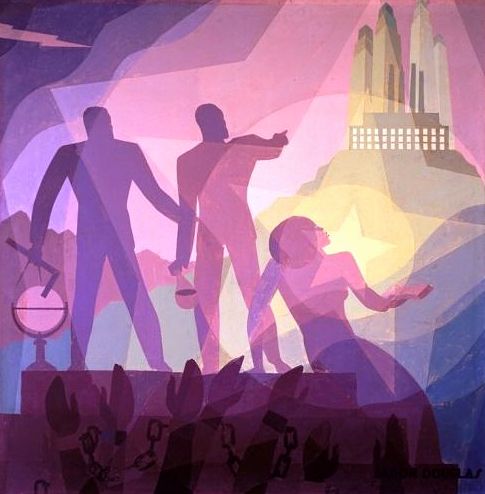

Partial view of the mural by Jerry Bywaters & Alexandre Hogue (1934)

by Paula Bosse

Several months ago, I was looking at the postcard of the Old Red Courthouse shown below. I thought it was interesting because I hadn’t seen that view before. And then I noticed what looked like a derrick just to the right of the courthouse. What was that? It looked like it was standing over a tank of water, kind of like a windmill. And then I got distracted and didn’t come back to it until I read of an (unrelated) old well having been uncovered in present-day Dealey Plaza a year or two ago, and I remembered this postcard. Was that a well? On the courthouse property? And now I know: it was, in fact, an artesian well that had been sunk on the courthouse lawn in the fall of 1890, and its success was an INCREDIBLY important factor in Dallas’ growth as a city.

In 1890, Dallas was growing at a remarkable rate, and like any large city, it needed a reliable source of water. In Dallas, that was a problem. Wells were dotted around town — many on private property — but a large supply of water for the ever-increasing community was needed, and needed fast. I gather things were reaching a critical point when The Dallas Morning News printed a letter from a reader named S. T. Stratton in January of 1890. Stratton, a long-time resident of Dallas, suggested digging an artesian well on courthouse property. (And while they were down there, they could check for the possibility of oil and gas.)

DMN, Jan. 8, 1890

DMN, Jan. 8, 1890

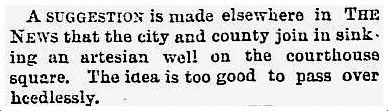

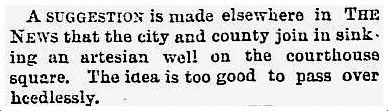

It seems that this might not have been an idea many people would have taken seriously at the time, because several pages away in the same issue of the paper was this little tidbit encouraging readers to seriously consider this as a viable option. (This was unsigned, but it seems likely it was written by DMN publisher G. B. Dealey.)

DMN, Jan. 8, 1890

DMN, Jan. 8, 1890

The idea gained popularity, and a “special committee on artesian water” convened in February, deciding to go forward with the plan; the city and the county would divide the cost.

DMN, Feb. 6, 1890

DMN, Feb. 6, 1890

Later in the year, drilling began, and on Oct. 9, 1890, water was hit. The flow at first was slow, but then, just like in the movies … a gusher! A Dallas News reporter had been writing a story on the initial success when, before he was able to file his report, the well suddenly became the biggest story in the city, in the state, and even around the country. When the drill hit 1,000 feet, the water began to shoot up with such force that it was estimated the well would produce in excess of one million gallons a day. There must have been incredible excitement in the wee hours of that morning, and the reporter’s story of the gusher is pretty thrilling to read — that last sentence is wonderful: “The water at 1 o’clock this morning was clear and it sparkled beautifully in the rays of electric lights.”

DMN, Oct. 10, 1990

DMN, Oct. 10, 1990

Below is the headline of the in-depth coverage of the successful well (full story linked at bottom of this page). Throngs of people crowded around the well, jubilant politicians patted themselves on the back, and men from the surrounding area wanted one for their towns (Marsalis declared he would get one for Oak Cliff, post haste!). What a scene it must have been. Finally, with that massive reservoir of water underneath the city, Dallas was assured of its continued growth.

DMN, Oct. 11, 1890

DMN, Oct. 11, 1890

A story that ran in the national business journal Manufacturer’s Record underlines the importance of the well’s discovery to business investors around the country:

This successful experiment effectively settles the water supply problem of Dallas, and it removes the last obstacle possible to be urged against the rapid building up of Dallas. It insures an unlimited supply of the finest water not only for domestic use, but for manufacturing purposes, which, taken in connection with cheap fuel and ample distributing facilities in a land where various lines of raw material abound, leaves no question as to the success of manufactures. (Quoted in the DMN, Oct. 21, 1890)

Not only was the well’s success being discussed in the national press, but it was also popping up in local ads, like this one from a real estate company which appeared in the pages of the DMN on Oct. 12, 1890:

THE ARTESIAN WELL

Is ‘a Thing of Beauty and a Joy Forever.’

And the hour the drill pierced the water-bearing strata and the precious fluid gushed forth at the rate of 1,000,000 gallons a day forms a new era in the history of the metropolis of the southwest. Every foot of ground in Dallas has increased in value by no inconsiderable amount, but the few lots left on the market in Hall’s second addition will still be sold at $100 each, easy terms.

So I’ve learned something new. I probably should have known about this, at least in connection with the series of PWAP murals produced in 1934 by Jerry Bywaters and Alexandre Hogue, two of my favorite Dallas artists. They painted ten murals throughout the old City Hall (later known as the Municipal Building), each illustrating a high point in the city’s history. The decade 1890-1900 was commemorated by a depiction of the artesian well and all that water discovered flowing beneath the grounds of the then-under-construction Dallas County Courthouse. Unbelievably, the murals were destroyed (!) when the building underwent renovation in 1956. Had they still been around, I probably would have seen them, and I would have learned about this whole artesian well thing many, many years ago!

Who is the sinister-looking man in the dark coat?

Who is the sinister-looking man in the dark coat?

*

A street-level view from about 1900, showing Commerce Street east from Houston Street showing the artesian well at the left — I believe this served as a public watering trough for horses.

via DeGolyer Library, SMU

via DeGolyer Library, SMU

*

UPDATE: I went to see the capped well today (July 20, 2014). It’s under a shady tree at the southwest corner of the Old Red Courthouse, at Commerce & Houston streets. It isn’t marked at all and is fairly inconspicuous. Even though I’ve known about the existence of this well for only a couple of days, I was so happy to see it — still there, where it’s been for almost 125 years. It was like seeing an old friend.

Photo by Paula Bosse

Photo by Paula Bosse

The view below (looking across Houston Street toward Dealey Plaza from Commerce) shows where this capped well is.

Google Street View (2011)

Google Street View (2011)

*

The wonderful photo below is from the 1920s and shows a young woman stopping for a drink on the courthouse lawn.

From the collection of Ann Hoffman

From the collection of Ann Hoffman

***

Sources & Notes

The color image of the Bywaters and Hogue mural is a photograph taken by Jerry Bywaters in 1956 before the murals were destroyed; the black and white photo is by Harry Bennett. Both are from The Bywaters Special Collections, Hamon Arts Library, Central University Libraries, Southern Methodist University. See more information on the color image here, and the black and white image here.

Both postcards are from the DeGolyer Library at SMU: the color postcard can be accessed here; the black and white one here. The black and white image has been cropped — missing is the amusing note on the front of the card, dated 1-4-07: “Dear Faye, can you imagine me a long-haired Texan, brandishing a bowie knife? Ross.”

The circa-1900 photograph showing the well at the left side of the photo is titled “East on Commerce, Commerce and Houston streets, 1900” and is from the Collection of Dallas Morning News negatives and copy photographs, DeGolyer Library, SMU — more info is here.

The photo of the young woman on the courthouse lawn is from the collection of Ann Hoffman and is used with permission; taken in the 1920s, it shows a friend of her Great Aunt Nora stopping for a drink of water. Thank you for sharing, Ann!

All news clippings from The Dallas Morning News.

To read the report of the initial, somewhat tentative early-in-the-day well success, the DMN article from Oct. 10, 1890 is in a PDF here. For the crazy, jubilant, people-beside-themselves-with-joy report of the gusher, the entire article from Oct. 11, 1890 is here.

Not exactly sure what an artesian well is? Wikipedia to the rescue, here.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

DMN, Jan. 8, 1890

DMN, Jan. 8, 1890 DMN, Jan. 8, 1890

DMN, Jan. 8, 1890 DMN, Feb. 6, 1890

DMN, Feb. 6, 1890 DMN, Oct. 10, 1990

DMN, Oct. 10, 1990 DMN, Oct. 11, 1890

DMN, Oct. 11, 1890

The Hall of Negro Life at the Texas Centennial Exposition, Fair Park

The Hall of Negro Life at the Texas Centennial Exposition, Fair Park

“Into Bondage” by Aaron Douglas, 1936 (Corcoran Gallery of Art)

“Into Bondage” by Aaron Douglas, 1936 (Corcoran Gallery of Art) “Aspiration” by Aaron Douglas, 1936 (Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco)

“Aspiration” by Aaron Douglas, 1936 (Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco)