The South End “Reservation” Red-Light District — ca. 1907

There’s a lot going on here that you can’t see… (DeGolyer Library, SMU)

There’s a lot going on here that you can’t see… (DeGolyer Library, SMU)

by Paula Bosse

I am reminded how much fun it is to just dive into something with no idea where you’re heading and end up learning interesting things you might have been unaware of had you not wondered, “What am I looking at?”

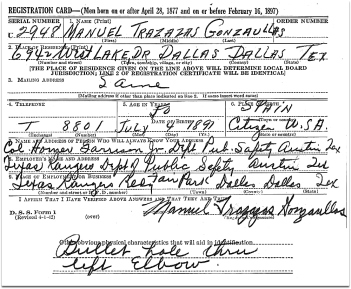

Yesterday I was working on a future post that involves the Hobson Electric Co., and I was looking for photos. The one above popped up in one of my favorite collections of historical Dallas photos, the George W. Cook Collection at SMU’s DeGolyer Library. I was looking for a post-1910 West End photo — this photo is identified as just that [the title has now been updated by the SMU Libraries], but the presence of the Schoellkopf Saddlery Co. building (center left, with the Coca-Cola ad on it) puts this location on the other side of the central business district — Schoellkopf was at S. Lamar and Jackson. Even knowing that, this scene didn’t look familiar at all.

I checked a 1907 city directory to find out the address of the Hobson Electric Co. before it moved to the West End in 1910 — it was located at 172-74 Commerce Street (in what is now the 700 block), between S. Market and S. Austin. The view here is to the southeast, probably taken from the courthouse.

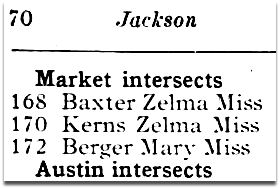

I don’t think I’ve seen this particular view before — it shows hardly any of the downtown area but shows instead the area to the south. I was really intrigued by the block of houses facing Jackson (between Market and Austin) — the block the horse-and-buggy is moving past, at the center right. The trees. The low buildings. That block really stood out. It was kind of quaint. Did people live there? While I had the 1907 directory open, I checked to see who the occupants were. (I just picked 1907 because the Hobson Co. changed its name from “Duncan-Hobson” around 1906, and it had moved away from Commerce by mid 1910.) Here were the occupants of those houses in 1907:

That seemed odd. Three single women occupying three separate houses, all next door to one other. There weren’t a lot of single women living in houses alone in 1907. Hmm. I checked all the directories between 1905 and 1910 to see who was living in that block. Every year, each of those houses showed a new occupant, and, with one exception, all were single woman (the exception was a man who owned a saloon across the street and who had faced charges at one point for “keeping a disorderly house”). …Okay. I got the picture.

I checked the Sanborn map from 1905 for this block and saw something I’d never seen before: the designation of a building with the letters “F.B.” What did that mean? Turns out, it means “Female Boarding House.” Or, less euphemistically… a brothel. Look at the map here (more maps are linked at the bottom of this post) to see the frankly ASTRONOMICAL number of “F.B.” buildings in this one small area. (There weren’t as many saloons — designated with “Sal.” — as I expected, but I’m pretty sure a lot of saloons in this area were operating illegally.)

You might have noticed that all of those F.B.s are south of Jackson. Not one of them is north of Jackson. This area — the southwestern part of downtown — was referred to at the time as the “South End” or “The Reservation” (some called this general area “Boggy Bayou,” but I think that was technically farther south). Its boundaries were, basically, S. Jefferson Street (now Record Street) on the west, Jackson on the north, S. Lamar(-ish) on the east, and beyond Young Street on the south. If you wanted to avail yourself of illicit things and engage in naughty behavior, this was the place for you: Ground Zero for a sort of wide-open, lawless Wild West. There were other red-light districts in Dallas (most notably “Frogtown,” which was north of downtown in the general area formerly known as Little Mexico) (does anyone still call this now-over-developed area “Little Mexico”?), but if you wanted the primo experience of one-stop-shopping for drinking, gambling, drugging, and “consorting with fallen women,” you were probably familiar with the South End, where all of these activities were tolerated and, for the most part, ignored by the police (they might mosey by if there were an especially egregious shooting or stabbing or robbery). In fact, this vice-filled area had been created by a helpful city ordinance in the 1890s. So, enjoy!

Prostitutes were allowed to ply their trade in this specified chunk of blocks because the city fathers felt that it would be best to keep all that sort of thing in one somewhat controllable area, away from the more reputable neighborhoods. But once a prostitute stepped outside the Reservation to sell something she shouldn’t have been selling… laws suddenly applied, and she’d be thrown in jail and/or fined. Do not step north of Jackson, Zelma!

So, at one time, Dallas had legal brothels. Depending on whose account you read, these houses of ill repute ranged from godawful “White Slavery” operations and bubbling cauldrons of sin and sleaze to, as Ted Dealey remembers in his book Diaper Days of Dallas (p. 74), “ultra-fashionable houses of prostitution” which attracted Big D’s moneyed movers and shakers. Something for everyone.

Eventually, people started to get really bent out of shape about this, and there was a big push to get these houses shut down — or at least moved out of the area. The Chief of Police reported to the City Council in 1906 that, among the many Reservation-related problems, the area was getting cramped because the railroads were buying up real estate in the area and kicking people out. The city-sanctioned no-man’s land was getting too small, so city officials needed to find a bigger place to move the red-light district to. The Chief thought that North Dallas (i.e. Frogtown) was “the most logical place” — except that residents of nearby swanky neighborhoods there were not at all keen on this. But that idea seemed to stick. It took several years to actually happen, but a relocation of sorts occurred, and the South End brothel-hotspot was pretty much scrubbed of all offending “disorderly houses” by 1910. (Frogtown bit the dust around 1913, after those unhappy well-to-do North Dallas neighbors complained bitterly, loudly, and effectively.)

So, anyway, I never expected to find such an exciting photograph! I wonder if the photographer took this photo as a way of documenting the very controversial, in-the-news, not-long-for-this-world Reservation, or whether it was just a nice scenic view. I have to think it was the former, because the Reservation was well-known to everyone, near and far, and this shot would have been an unusual vista to, say, reproduce for postcards (or at least postcards sold to the general public!). Whatever the case, I’ve never seen this view, and it’s really great — and it comes with an interesting slice of Dallas history. I had heard of the Frogtown reservation to the north, but I’d never heard of the South End reservation. And now I have. And here’s a photo of it!

Let’s bring back the neighborhood designation of “South End.” It was good enough for 1900, it’s good enough for today.

*

Here are a few zoomed-in details of the photo. Unless I’m imagining things, I think I can see women sitting on their porches, advertising their wares, as was the custom. (All images are larger when clicked.)

*

*

*

Below is an excerpt from a blistering directive to city lawmakers by W. W. Nelms, Judge of the Criminal District Court (from an article with the endless headline “Calls For Action; Judge Nelms Charges Police Chief, Sheriff and Grand Jurors; Warfare on Crime; Says Lawbreakers Shall Not Construe Statutes of State to Suit Themselves; Stop Murder and Robbery; Declares Harboring Places for Thugs, Thieves and the Like Must Be Destroyed,” Dallas Morning News, Oct. 15, 1907).

*

Below, the general area of the South End Reservation around 1907 (this map is from about 1898). The blue star is the Old Red Courthouse; the Reservation is bordered in red. In 1893, the original area was loosely designated as the area bounded by Jackson Street, Mill Creek, the Trinity River, and the Santa Fe railroad tracks, in which “women of doubtful character […] were not to be molested by police” (from “Passing of Reservation,” DMN, Dec. 11, 1904). As noted above, the area shrank over time, and the red lines show the general Reservation area about 1907, the time of the photo at the top.

Dallas map, ca. 1898 (det), via Portal to Texas History

Dallas map, ca. 1898 (det), via Portal to Texas History

***

Sources & Notes

Top photo — “[Jackson Street, Looking Southeast from the Courthouse, Including a Partial View of the South End ‘Reservation’]” (previously incorrectly titled “[Dallas West End District with View of Railroad Yards]”) — is from the George W. Cook Dallas/Texas Collection, DeGolyer Library, SMU Libraries and can be accessed here. (I appreciate SMU for responding to my request to re-title and re-date this photograph — it’s always worth notifying archival collections with corrections!) (And, as always, I WELCOME corrections. I make mistakes all the time!)

The 1905 Sanborn map I linked to above (Sheet 104) is here and seems to be the epicenter of the booming brothel trade; more evidence of this can be seen just south of that in Sheet 102; and it continues just east of that in Sheet 105 (it’s interesting to note the specially designated “Negro F.B.” bawdy houses). (Sanborn maps do not open well on cell phones — or at least on my cell phone. You may have to access these from a desktop to see the full maps. …It’s worth it.)

Read more about this whole “Reservation” thing in the lengthy and informative article “Not in My Backyard: ‘Legalizing’ Prostitution in Dallas from 1910-1913” by Gwinnetta Malone Crowell (Legacies, Fall 2010).

Also, there’s a good section on this (“Fallen Women”) in the essential book Big D by Darwin Payne (pp. 48-56 in the revised edition).

If you enjoy these posts, perhaps you would be interested in supporting me on Patreon for as little as $5 a month — in return, you have access to (mostly!) exclusive daily Dallas history posts. More info is here.

*

Copyright © 2024 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

Dallas Morning News headline, May 4, 2022/photo: Tom Fox

Dallas Morning News headline, May 4, 2022/photo: Tom Fox

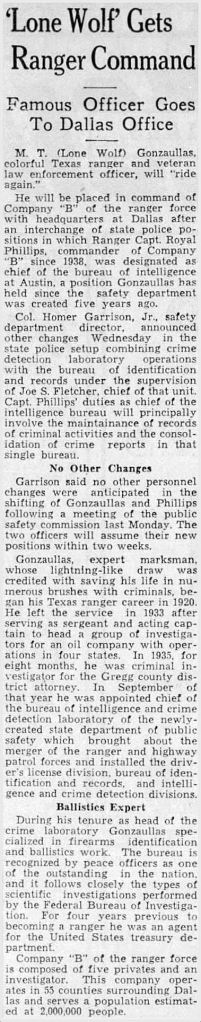

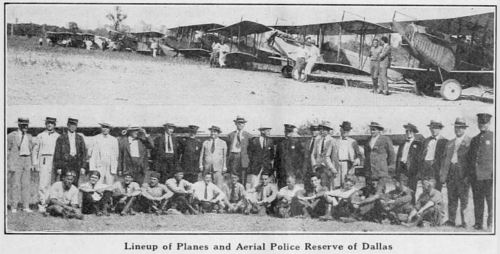

Jan. 20, 1972

Jan. 20, 1972