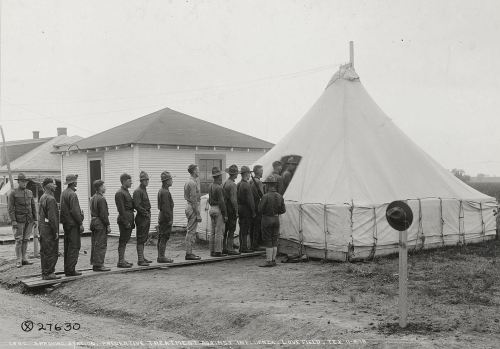

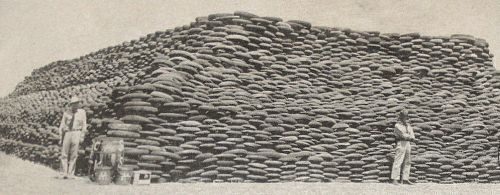

Guarding wartime scrap rubber, near Love Field…

by Paula Bosse

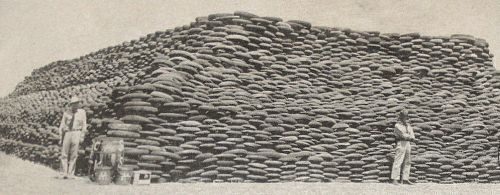

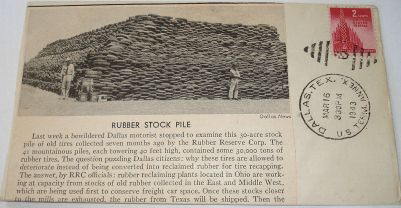

You don’t see this everyday: a photo of a pile of tires so large it dwarfs the armed guards who stand in front of it. (For that matter, you don’t often see armed men guarding tires.) What’s going on here? All is explained in the accompanying Time magazine article from March, 1943, which appears to have been cut from the magazine and pasted onto an envelope.

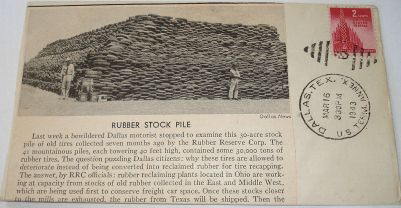

The article reads:

RUBBER STOCK PILE

Last week a bewildered Dallas motorist stopped to examine this 30-acre stock pile of old tires collected seven months ago by the Rubber Reserve Corp. The 41 mountainous piles, each towering 40 feet high, contained some 30,000 tons of rubber tires. The question puzzling Dallas citizens: why these tires are allowed to deteriorate instead of being converted into reclaimed rubber for tire recapping. The answer, by RRC officials: rubber reclaiming plants located in Ohio are working at capacity from stocks of old rubber collected in the East and Middle West, which are being used first to conserve freight car space. Once these stocks closer to the mills are exhausted, the rubber from Texas will be shipped. Then the 25 armed guards, who watch Dallas’s [illegible] day and night, can go home.

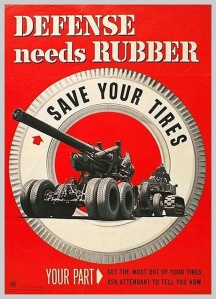

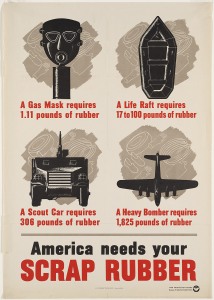

Ah, that mound of tires was the result of one of World War II’s many scrap drives. The national rubber drive ran from June 15, 1942 until July 10, 1942. The government requested that all Americans collect any old or unused rubber items in order to help with the supply of rubber in the U.S. (Japan controlled the bulk of rubber imports, and those imports had stopped when the United States entered the war). Rubber was needed for military purposes, but it was also necessary for essential domestic needs, mainly as tires needed to transport goods and people. Americans were told they needed to treat their automobile’s tires like gold: drive safely, drive slowly, and drive only when necessary — don’t wear your tires out, because you don’t know how long it’ll be until they’re manufactured again and/or how long it will be until large-scale production of synthetic rubber would become a reality.

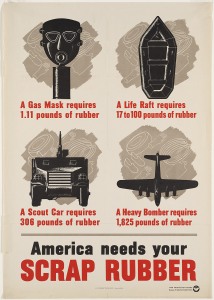

Posters via SarahSundin.com

Posters via SarahSundin.com

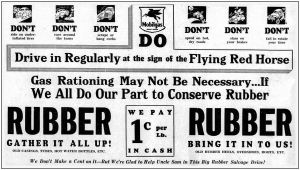

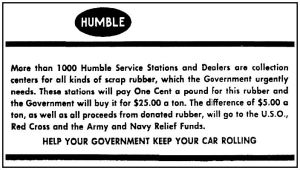

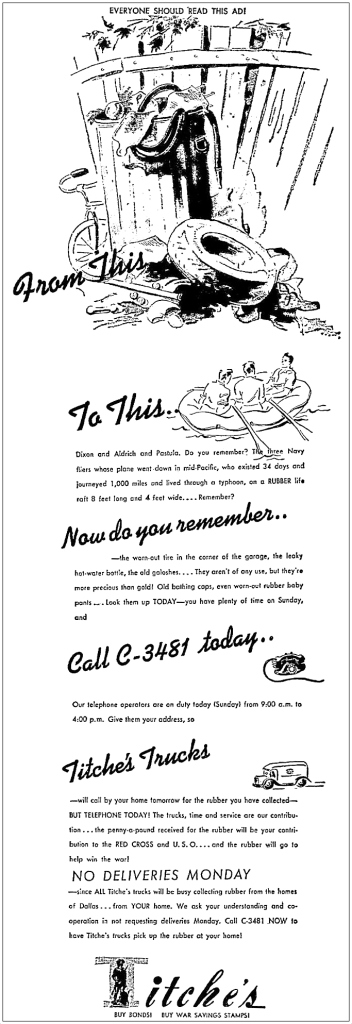

When the rubber drive began, people were basically told that if they collected enough scrap rubber, the dire prospect of nation-wide gas rationing might be unnecessary (at the time only a few states in the northeast had been suffering through the rationing of gasoline) — the thinking was that if the government withheld gasoline that citizens would conserve rubber simply because they were unable to drive as much. Texans really like their cars and trucks, and we have long distances to drive, so it’s no surprise that throughout the rubber drive, Texas out-performed almost every state in per capita tonnage collected. In the first day of the drive, a Dallas gas station at Harwood and Young reported that 4,500 pounds of collected scrap rubber had been left throughout the day by Dallasites performing their patriotic duty. And that was just one day and one gas station! The government was paying a penny a pound, but many people refused payment.

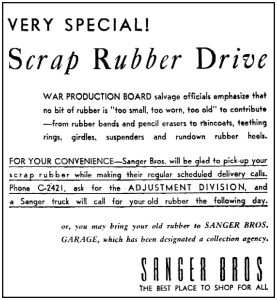

What sorts of things were people dropping off at their neighborhood gas station (the government-directed drop-off points)? Other than used tires, everything you could imagine:

- Automobile floor mats

- Galoshes and raincoats

- Bathing caps

- Hot water bottles

- Garden hoses

- Girdles

- Doorstops

- Tennis and golf balls

- Rings from jelly jars

- Baby pants

- Dolls

- Toy mice

- Slingshots

- Soles of athletic shoes

- Roadside debris

- Mats found under office furniture and cuspidors

That stuff adds up fast.

*

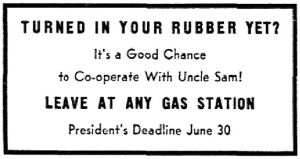

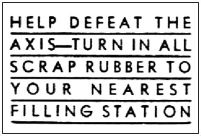

Below are several ads exhorting readers to do their bit for the war effort by collecting and donating scrap rubber during the national rubber drive. (All images are larger when clicked.)

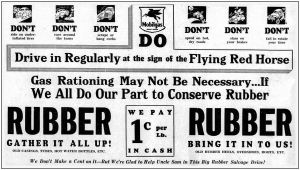

Mobil ad detail, June 16, 1942

Mobil ad detail, June 16, 1942

Scrap could be dropped off at any service station.

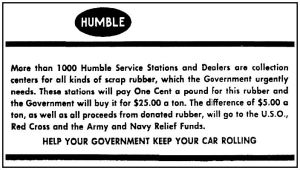

Humble Oil ad detail, June 17, 1942

Humble Oil ad detail, June 17, 1942

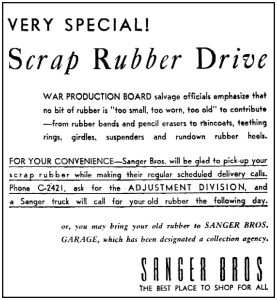

If you needed home pick-up service, Sanger Bros. would send a truck.

Sanger Bros. ad, June 16, 1942

Sanger Bros. ad, June 16, 1942

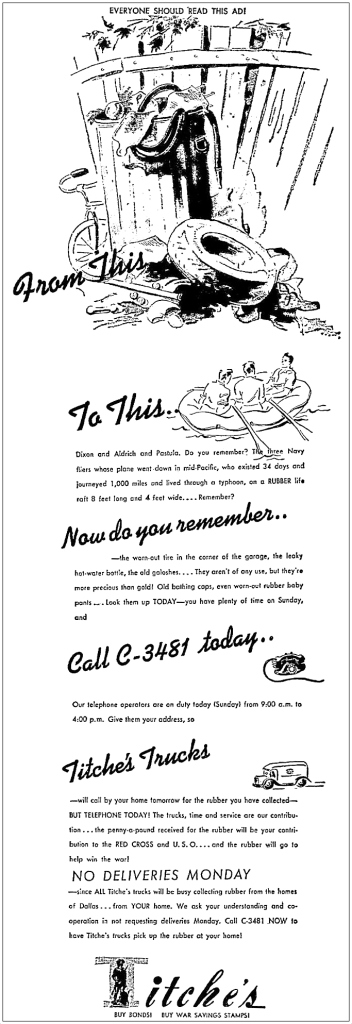

As would Titche’s.

Titche’s ad, June 21, 1942

Titche’s ad, June 21, 1942

Reminders to ferret out that rubber were added to many advertisements, as seen in this detail from a larger grocery store ad. (The drive was originally intended to run through June 30, but ended up being extended through July 10.)

Safeway ad detail, June 26, 1942

Safeway ad detail, June 26, 1942

This appeared in an ad from the men’s and boys’ clothing store Reynolds-Penland.

Reynolds-Penland ad detail, June 26, 1942

Reynolds-Penland ad detail, June 26, 1942

As well as things were going in Big D, according to the government, things weren’t going well nationally, and the powers-that-be were more loudly threatening gas rationing for the entire country, including the states which were actually collecting the most, Texas and California.

Austin Statesman, June 27, 1942

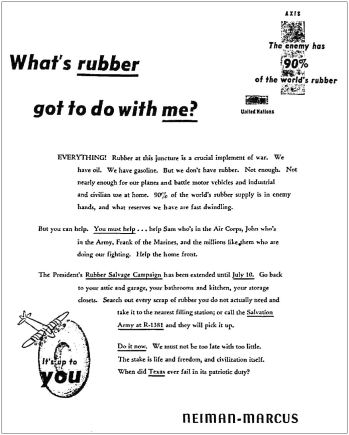

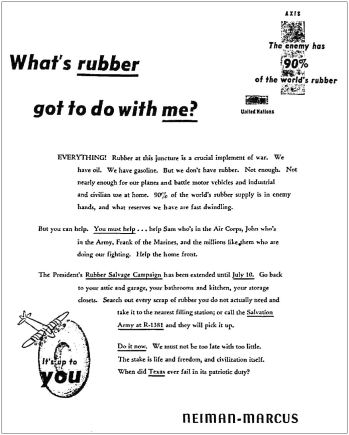

The deadline was extended until July 10, with hopes that people would knuckle down and collect much, much more. This Neiman’s ad asked the question “What’s rubber got to do with me?” and answered its own question with an emphatic “EVERTHING!” The ad ended with a barn-burner: “We must not be too late with too little. The stake is life and freedom, and civilization itself. When did Texas ever fail in its patriotic duty?”

Neiman-Marcus ad, July 3, 1942

Neiman-Marcus ad, July 3, 1942

The drive ended with Texas and the western states collecting the most scrap rubber. At the very bottom were New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, all of which were already rationing gasoline. Ultimately, FDR considered the rubber drive to have been a failure, but, like the other scrap drives, it whipped up patriotism and resulted in a feeling of shared community as people worked together for the sake of the country — something which might have been more valuable than rubber.

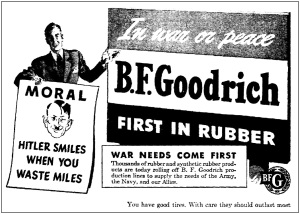

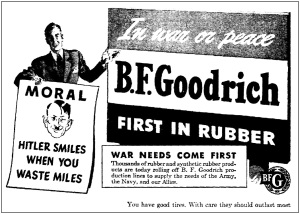

Synthetic-rubber production slowly increased, but, even so, tire manufacturer B. F. Goodrich wanted everyone to continue to make sure their tires lasted as long as possible, because, after all, ” Hitler smiles when you waste miles.”

B. F. Goodrich Tires ad detail, July 17, 1942

B. F. Goodrich Tires ad detail, July 17, 1942

**

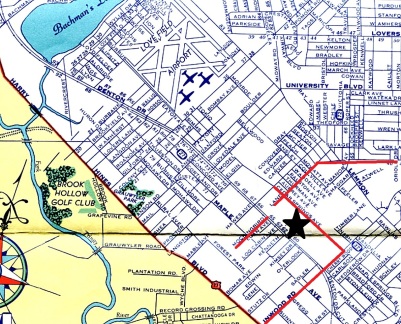

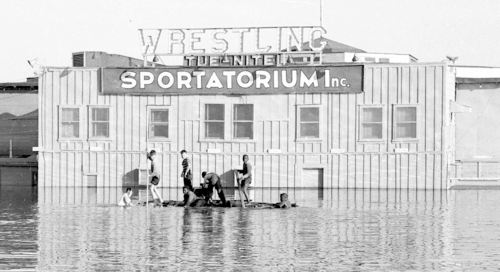

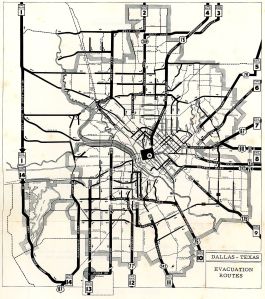

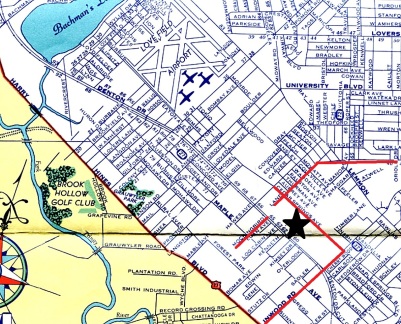

So where exactly was that massive used-tire mountain range? According to The Dallas Morning News, it was in a large open field “at the intersection of the MKT Railroad switch and Cedar Springs, just west of the Coca-Cola plant” (DMN, July 13, 1942), between Inwood and W. Mockingbird, not far from Love Field. The map below (from 1949) shows the general location of the yard, marked with a black star.

1949 Ashburns’ map detail, via DFW Freeways site

1949 Ashburns’ map detail, via DFW Freeways site

Initially, the salvage yard was to be contained on a 13-acre plot of land, surrounded by an 8-foot board fence. There were to be several tall guardhouses, and the “precious pile of vital war material” would be patrolled 24 hours a day by armed guards “to protect it from fire hazards, thieves, or saboteurs” (DMN, Aug. 6, 1942). The fear of a potentially huge and uncontrollable fire was the main concern — a special fire plug was installed on the property and a direct phone/alarm line to the central fire station was set up. By August, the size of the yard increased by 50% to accommodate the 30 or more freight carloads which were arriving daily with scrap rubber from all over Texas (except the Panhandle). This huge salvage yard was meant to hold the rubber-drive scrap until reclamation plants in Ohio could accommodate it.

Several months later, the Time article put the expanded size of the yard at 30 acres, containing 30,000 tons of rubber material. By January, 1944, it was estimated the mammoth tire graveyard contained a whopping one million tires. Rather anti-climactically, a local tire dealer was contracted by the Rubber Reserve Corporation to “pick out the repairable and recappable carcasses” (DMN, Jan. 23, 1944) which were estimated to number about 150,000 tires; they would then be dispersed to Texas dealers who would either sell them to consumers or vulcanize them. Despite the frenzied rubber drive of 1942 and almost a year and a half of sitting forlornly in an open field guarded by men with guns, it looks like those tires never made their trip to Ohio.

*

The land that these “tire mountains” occupied appears to have been leased from Carl C. Weichsel, member of a noted Dallas pioneer family. 23 acres of the land was sold to the Coca-Cola Company in 1937 — a $1,000,000 syrup plant and warehouses were built on ten of the acres, at Lemmon and W. Mockingbird. (Coca-Cola bought ten more acres in 1947 in order to expand.) A few weeks after the Coca-Cola land-purchase was announced, Dallas County granted the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railway right of way across Cedar Springs, just south of Mockingbird, for a switch track to the Coca-Cola plant.

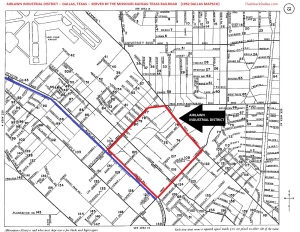

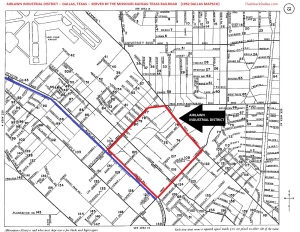

In the mid 1940s, the Airlawn Industrial District sprang up in this area. The planning and development of Airlawn was spearheaded by none other than the Katy Railroad, beginning when Coca-Cola decided to move to the area.

The […] plans were drawn up by the Katy’s industrial research and development department with the aid of experts versed in the problems of present day industry. […] The Katy maintains a Diesel switch engine on duty twenty-four hours a day to handle the switching operations in the Airlawn area. One section gang is assigned to this area to maintain the miles of track that interweave the industrial buildings. (DMN, Oct. 9, 1949)

The MKT was working to attract businesses along their lines: they needed the businesses, and the businesses needed them. Win-win! (It’s interesting to note that another major manufacturer that the Katy worked with on securing a location was another soft drink company: the Dr Pepper plant on Mockingbird, near Central.)

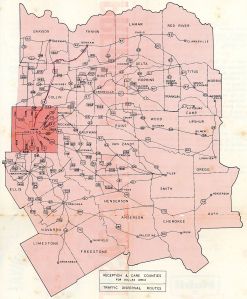

Below is a map from 1952 which shows the railroad spurs which were used by the Airlawn businesses. I’m not sure why I find this so interesting, but I do! (Are these tracks still in use?)

1952 Dallas Mapsco

1952 Dallas Mapsco

***

Sources & Notes

First and second image are from an old eBay listing; it appears that someone pasted a Time magazine article (March 15, 1943) to an envelope; the postmark and cancellation shows that it was mailed from Dallas on March 16, 1943, even though there does not appear to be an address on the front or back of the envelope.

A really interesting article on the various WWII scrap drives — “Getting In the Scrap: The Salvage Drives of World War II” by Hugh Rockoff, of the Economics Dept. of Rutgers University — is well worth a read, here. From his abstract: “While the impact of the drives on the economy was limited, the impact of the drives on civilian morale, may well have been substantial.”

Another very informative article on the national rubber drive of 1942 can be found in the post “Make It Do — Tire Rationing in World War II” by Sarah Sundin, here.

See a variety of patriotic posters encouraging Americans to participate in WW2 scrap drives here.

Pertinent Dallas Morning News articles about this rubber salvage yard:

- “Work Begun on Rubber Storage Plant” (DMN, July 13, 1942)

- “Close Guard Is Kept On Rubber” (DMN, Aug. 6, 1942 — includes a photo of the yard, similar to the one that appeared in Time magazine)

- “150,000 Usable Tires Believed Salvageable From Waste Pile” (DMN, Jan. 23, 1944)

*

Copyright © 2019 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved