Send Your Kids to Prep School “Under the Shadow of SMU” — 1915

Powell University Training School, 1915

Powell University Training School, 1915

by Paula Bosse

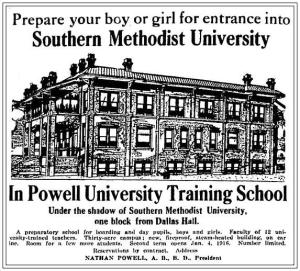

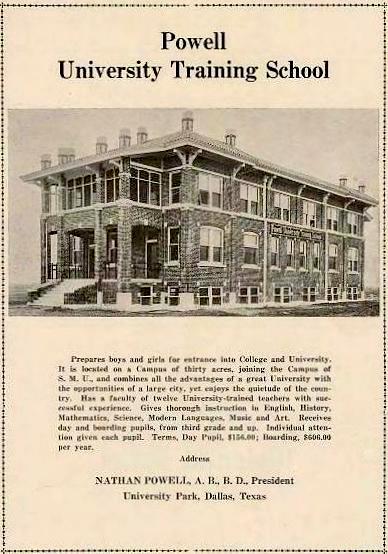

Nathan Powell (1869-1963) was a former Methodist minister who opened his prep school, Powell University Training School, on thirty acres of open land, just across an unpaved road from SMU (which was still in the very early days of its construction). SMU and the Powell school shared more than just adjacent addresses — which they both rather idealistically touted as being “situated on high ground overlooking the university campus and the city” — they also opened on the same day, September 15, 1915.

The location and the opening date were not a coincidence, as Dr. Powell was one of the Methodist movers and shakers who originally promoted the idea of Dallas as the site for a new Methodist university. The following (perhaps exaggerated) sentence can be found in the (perhaps overly laudatory) profile of Powell in one of those ubiquitous late-19th, early-20th century “mug books,” A History of Texas and Texans (1916):

Beyond his activities as a minister and teacher, the most notable achievement in the life and career of Doctor Powell lies in the fact that he was the sole originator and promoter of the great Southern Methodist University at Dallas, which began its first year September 15, 1915.

Powell University Training School lasted for only about twelve years, until Powell’s rather sudden retirement in 1927 (the good reverend’s “retirement” might have been precipitated by numerous lawsuits and mounting debt). When the school closed, Dr. Powell and his family moved to Harlingen to — as his obituary states — “help organize the grapefruit growers of the Rio Grande Valley.” He operated a citrus nursery himself for a while until it was destroyed by a 1933 hurricane. Nathan Powell died in Harlingen in 1963 at the age of 94.

It’s always exciting to see old buildings still standing in Dallas, and, happily, this one is still around — and it still looks good. Fittingly, it’s currently home to an early-child development center. Next time you’re near the intersection of Binkley and Hillcrest, go take a look.

*

*

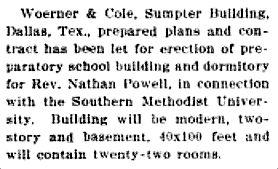

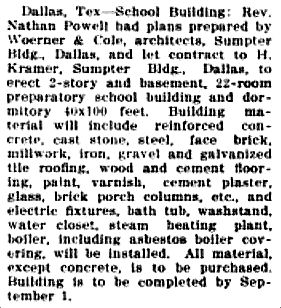

* Both items from the Texas Trade Review & Industrial Record, July 15, 1915

Both items from the Texas Trade Review & Industrial Record, July 15, 1915

SMU Times, Dec. 18, 1915 (click for larger image)

SMU Times, Dec. 18, 1915 (click for larger image)

SMU Times, Dec. 18, 1915

SMU Times, Dec. 18, 1915

Below, after the school closed. Looking a little shaggy. I would have guessed the photo was from much earlier, but it’s dated 1931. Complete with horse.

1931, Brown Book, University Park Public Library

1931, Brown Book, University Park Public Library

***

Sources & Notes

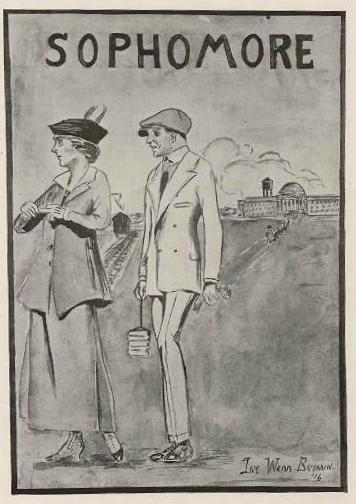

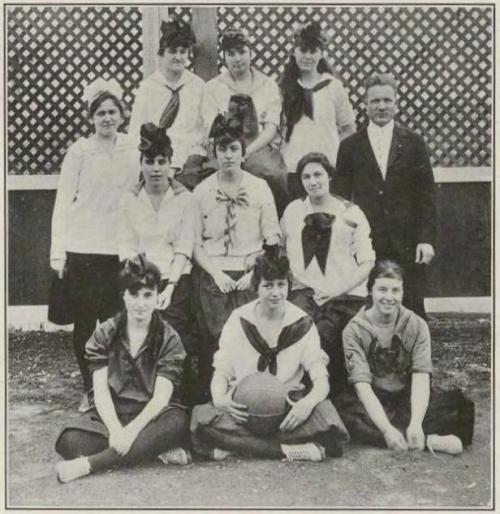

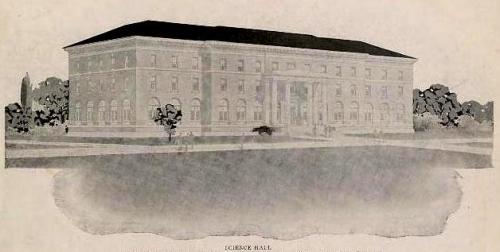

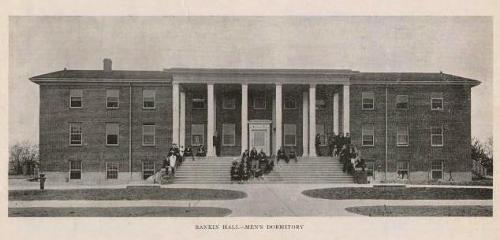

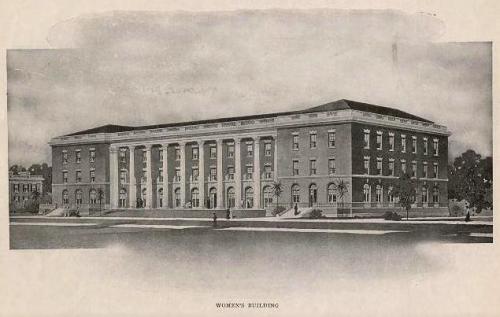

Top image and bottom ad appeared in the very first edition of The Rotunda, SMU’s yearbook for their inaugural year, 1915-16.

More on Rev. Powell’s early life and involvement with the founding of Southern Methodist University can be read in A History of Texas and Texans by Frank W. Johnson (Chicago and New York: American Historical Society, 1916), here.

Information regarding Powell’s retirement in Harlingen is from “The Chronological History of Harlingen” by Norman Rozeff (circa 2009), in a PDF here.

Powell’s obituary can be found in The Dallas Morning News, Nov. 8, 1963: “Dr. Powell Dies; Helped Found SMU.”

Currently occupying 3412 Binkley is The Community School of the Park Cities. According to the history page of their website (here), the building has been operated as a school since at least the 1950s.

I’m not sure what the actual facts are concerning Nathan Powell’s role in the founding of SMU. There are very few results when searching the internet. Most newspaper articles connecting him with the university seem to have been generated by Powell himself. If Powell was as important in the history of SMU as he claimed to be, it’s surprising to see so little information on any connection. Was Powell’s assertion that he was the driving force behind the creation of SMU a blatant lie? Was it merely an exaggeration of the truth? Or was it accurate, but something happened to cause the university to distance itself from him? A collection of papers in the SMU archives (which I have not seen) seems to indicate that there were those in Methodist circles who disputed Powell’s claims, as Elijah L. Shettles took it upon himself to prove that Nathan Powell was the driving force behind the very existence of SMU. An overview of the collection — The Elijah L. Shettles Papers on the Founding of Southern Methodist University — can be found here.

(I’ve found an article from the Fort Worth Star-Telegram in 1910 that had Powell all but saying Fort Worth — not Dallas — would be the best choice for the university’s location. Read that article and see other photos of the school — and also read about the lawsuit against Powell (which had nothing to do with SMU) that took thirteen years to reach trial and ended in quite a hefty judgement, in a PDF here.)

See more of SMU’s first year in previous posts here and here.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

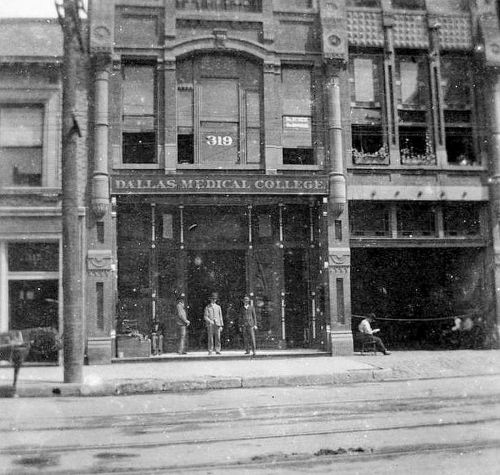

Dallas Morning News, Feb. 3, 1901

Dallas Morning News, Feb. 3, 1901

Southern Mercury, Nov. 10, 1904

Southern Mercury, Nov. 10, 1904

April 3, 1920

April 3, 1920 April 10, 1920

April 10, 1920 October 20, 1923

October 20, 1923 May 22, 1920

May 22, 1920 1950

1950

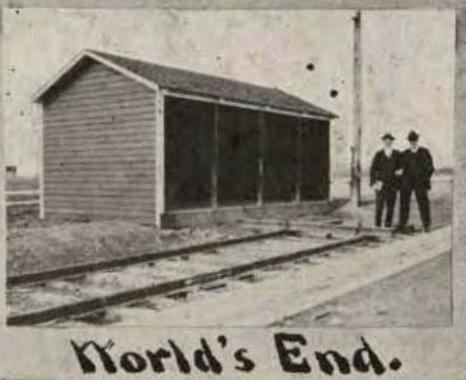

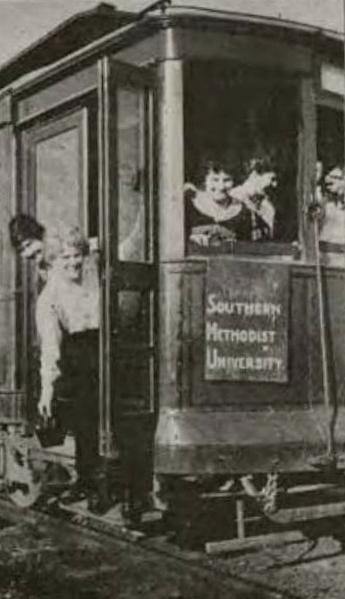

The “depot” where the Dinkey picked up and dropped off SMU students, faculty, and visitors.

The “depot” where the Dinkey picked up and dropped off SMU students, faculty, and visitors. The Dinkey, garnished with co-eds.

The Dinkey, garnished with co-eds.

Bad season?

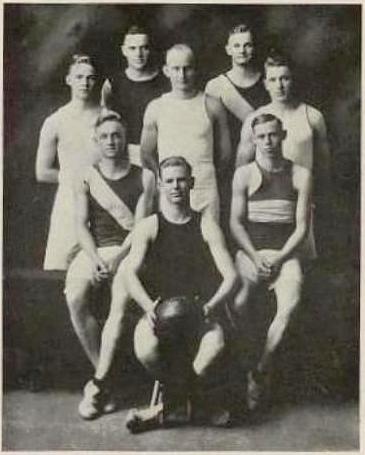

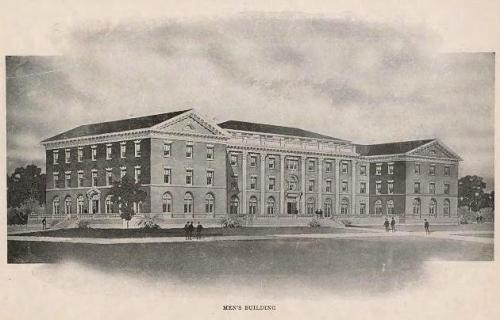

Bad season? The men’s “Basket Ball” team.

The men’s “Basket Ball” team.

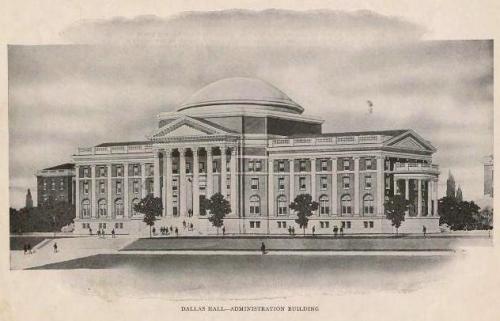

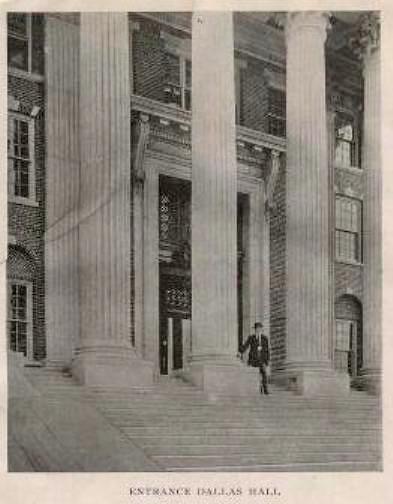

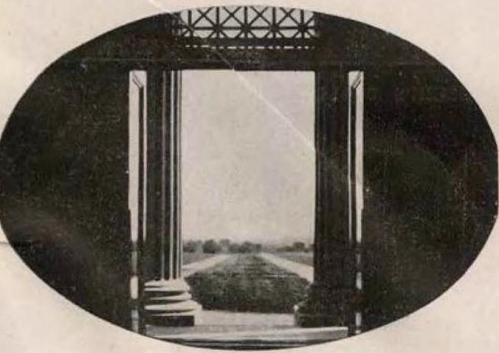

Entrance Dallas Hall

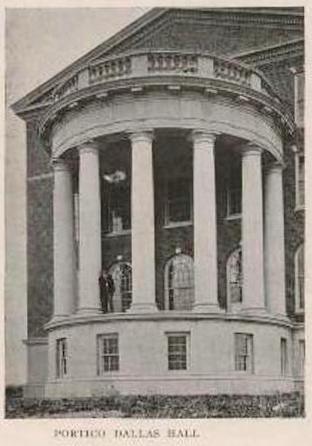

Entrance Dallas Hall Portico Dallas Hall

Portico Dallas Hall

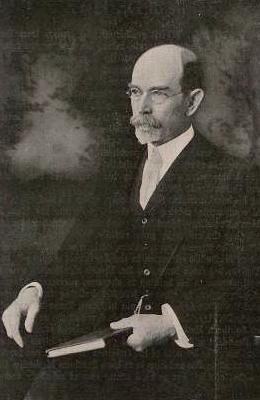

SMU President Robert Stewart Hyer

SMU President Robert Stewart Hyer

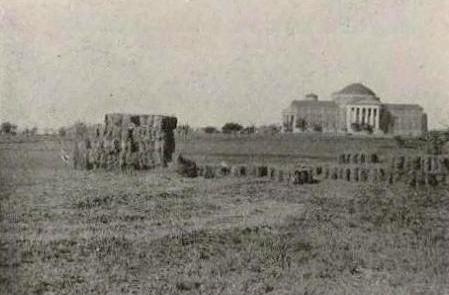

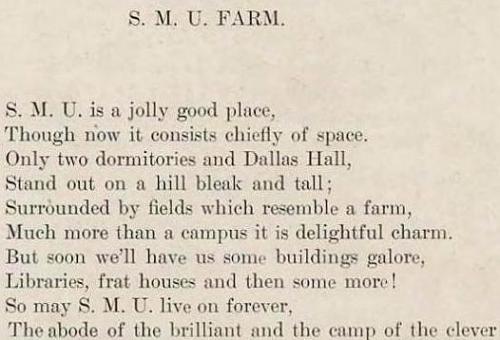

Dallas Hall, bales of hay, and stilted-yet-charming student versification

Dallas Hall, bales of hay, and stilted-yet-charming student versification