The Marietta Mask

SMU football star Doak Walker in an ad from Boys’ Life, Oct. 1955

SMU football star Doak Walker in an ad from Boys’ Life, Oct. 1955

by Paula Bosse

Dr. Thomas M. Marietta (1910-1995), a Dallas dentist, devised a startlingly new invention in 1947: a specially-made facemask. Initially, the mask was created to protect the face of a Dallas hockey player who had recently sustained a broken nose and would have been unable to play without a mask for fear of further injury. Marietta’s creation was a success — not only did the player get back on the ice, but tentative inquiries from other sports teams began to trickle in. But what changed everything were the masks he made for TCU’s star quarterback Lindy Berry, who had suffered a broken jaw, and Texas A&M’s fullback Bob Smith, who had a badly broken nose. Without the odd-looking masks that protected their entire faces, they would not have been able to play out the seasons. The masks were an unqualified success, and the doc went commercial.

Dr. Marietta (Marion Ohio Star, Nov. 22, 1951 — full article is here)

Dr. Marietta (Marion Ohio Star, Nov. 22, 1951 — full article is here)

In 1951, football players did not generally wear facemasks. It was commonplace for players to rack up a dizzyingly large number of injuries such as broken and dislocated jaws and noses, knocked-out teeth, facial lacerations, major bruising, concussions, etc. An article appeared in The Dallas Morning News on Aug. 31, 1951 describing what this whole facemask thing was about and how the Texas Aggies were about to try a revolutionary experiment by equipping “possibly half of the A&M team” with Dr. Marietta’s newfangled masks. Coach Ray George approved a trial test of the masks, saying that his primary concerns were reduction of facial injuries, elimination of head injuries, and improvement of athletic performance. A&M’s trainer, Bill Dayton, predicted that the wearing of facemasks would become universal among players in the coming years.

Many head injuries happen as the result of a player ducking his head. We believe that by the use of this face gear we can eliminate head ducking, and our players will see where they are going. When they watch their opponents, they are able, by reflective action, to keep their heads out of the way. (A&M trainer Bill Dayton, DMN, Aug. 31, 1951)

The various incarnations of the Marietta Mask over the next couple of decades were used in various sports by children, by college athletes, and by professionals. Dr. Marietta patented several designs for masks and helmets and had a lucrative manufacturing business for many years. In 1977 the business was sold, and the Marietta Corp. became Maxpro, a respected name in helmets.

Football and hockey will always be extremely physical sports with the very real possibility of injury, and though there’s need for further improvement, Dr. Marietta’s invention helped lower the danger-level quite a bit. Thanks to a mild-mannered dentist from Dallas, a lot of athletes over the years managed to avoid all sorts of nasty head and facial injuries. Thanks, doc.

*

Oct. 1954 (©Bettmann/CORBIS)

Oct. 1954 (©Bettmann/CORBIS)

***

Sources & Notes

Photo ©Bettmann/CORBIS; the original caption: “An outer-space look is given by this all-plastic mask lined with foam rubber. It was designed by Dr. M. T. Marietta, a Dallas, Texas dentist.”

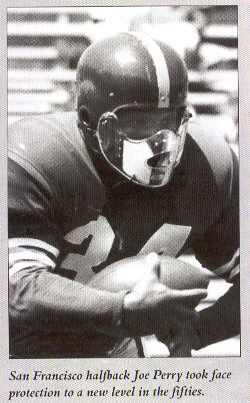

Joe Perry photo from HelmetHut. To see some pretty wacky versions of early masks from a Marietta catalog, see images from HelmetHut.com, here.

Read the following newspaper articles:

- “Mask Maker: Dentist Helped Wolves Win Title (Abilene Reporter-News, Nov. 29, 1950) — regarding the Colorado City (TX) Wolves and their injured player, Gerald Brasuell, the team’s tackle who wore Dr. Marietta’s mask and was able to play despite having a triple-fracture to his jaw, here

- “Broken Jaw Protection: Doctor’s Face Mask Enables Injured Gridders To Play” (Marion, Ohio Star, Nov. 22, 1951), here

To see several of Marietta’s patents (including abstracts and drawings), see them on Google Patents, here.

And to read an interesting and entertaining history of the football facemask (and I say that as someone who isn’t really a sports person), check out Paul Lukas’ GREAT piece “The Rich History of Helmets,” here. (If nothing else, it’s worth it to see the cool-but-kind-of-weird-and-scary, crudely-fashioned, one-of-a-kind facemask made out of barbed wire wrapped in electrical tape!)

And because a day without Wikipedia is like a day without sunshine, the facemask/face mask wiki is here.

*

Copyright © 2015 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

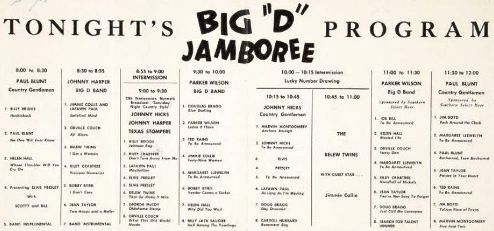

1939 Peruna (SMU Rotunda)

1939 Peruna (SMU Rotunda) 1960 Peruna (SMU Rotunda)

1960 Peruna (SMU Rotunda)

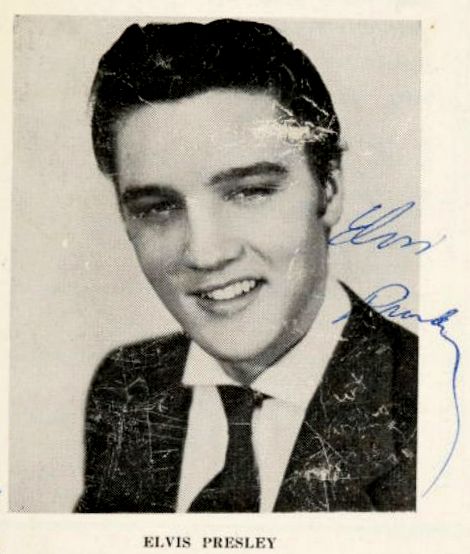

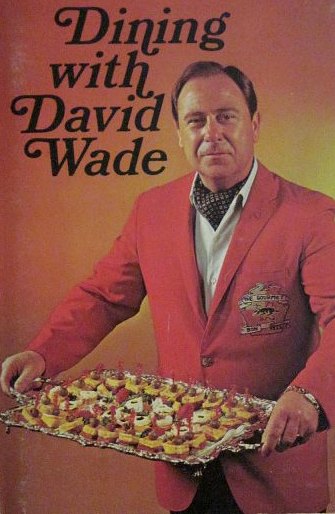

17-year-old David Wade, Waco High School, 1941

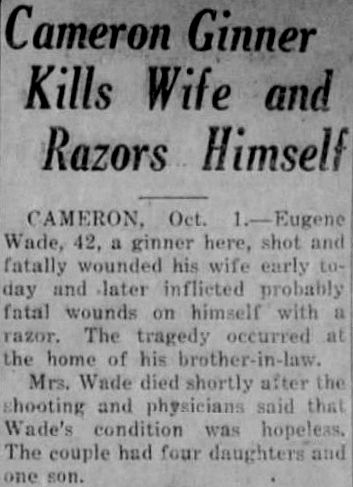

17-year-old David Wade, Waco High School, 1941 The Bryan Eagle, Oct. 1, 1929

The Bryan Eagle, Oct. 1, 1929

Bon Appétit!

Bon Appétit!

With Gregory Peck, 1960s

With Gregory Peck, 1960s

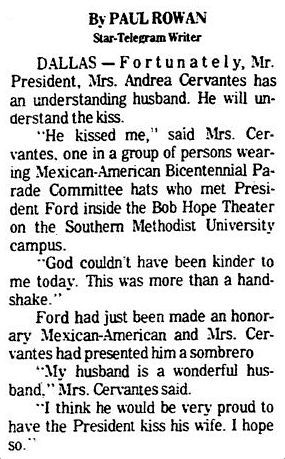

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Sept. 14, 1975

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Sept. 14, 1975