Roth’s, Fort Worth Avenue

by Paula Bosse

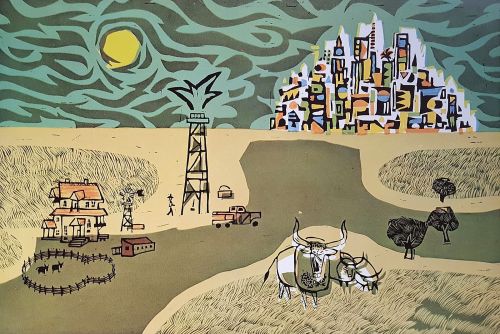

When I see a building like this, I always hope I can find a photo of it somewhere, but all I’ve been able to come up with is this energetic rendering from a 1940s matchbook cover. Roth’s (which was advertised variously as Roth’s Cafe, Roth’s Restaurant, and Roth’s Drive-In) was in Oak Cliff, on Fort Worth Avenue. It opened in about 1940 or ’41 and operated a surprisingly long time — until about 1967. When Roth’s opened, its address was 2701 Fort Worth Avenue, but around 1952 or ’53 the address became 2601. (I think the numbering might have changed rather than the business moving to a new location a block down the street.)

During World War II, Mustang Village — a large housing development originally built for wartime workers (and, later, for returning veterans and their families) — sprang up across Fort Worth Avenue from the restaurant. It was intended to be temporary housing only, but because Dallas suffered such a severe post-war housing shortage, Mustang Village (as well as its sister Oak Cliff “villages” La Reunion and Texan Courts) ended up being occupied into the ’50s. Suddenly there were a lot more people in that part of town, living, working, and, presumably, visiting restaurants.

As the 1960s dawned, Mustang Village was just a memory, and Roth’s new across-the-street neighbor was the enormous, brand new, headline-grabbing Bronco Bowl, which opened to much fanfare in September 1961. I don’t know whether such close proximity to that huge self-contained entertainment complex hurt or helped Roth’s business, but it certainly must have increased traffic along Fort Worth Avenue.

Roth’s continued operations until it closed in 1967, perhaps not so coincidentally, the same year that Oak Cliff’s beloved Sivils closed. Ernest Roth, like J. D. Sivils, most likely threw in the towel when a series of “wet” vs. “dry” votes in Oak Cliff continued to go against frustrated restaurant owners who insisted that their inability to sell beer and wine not only damaged their own businesses but also adversely affected the Oak Cliff economy. The last straw for Sivils and Roth may have been the unsuccessful petition drive in 1966/1967 to force a “beer election” (read about it here in a Morning News article from Aug. 17, 1966).

As far as that super-cool building seen at the top — I don’t know how long it remained standing, but when Roth’s closed, a mobile home dealer set up shop at 2601 Fort Worth Avenue, and mobile homes need a lot of parking space….

The building on the matchbook cover above is, unfortunately, long gone (as is the much-missed Bronco Bowl); the area today is occupied by asphalt, bland strip malls, and soulless corporate “architecture” (see what 2701 Fort Worth Avenue looks like today, here).

*

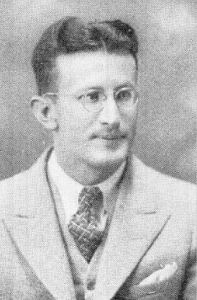

The man behind Roth’s was Ernest W. Roth, a Hungarian immigrant who had worked for many years as maître-d’ at the Adolphus Hotel’s tony Century Room. He decided to go out on his own, and around 1940, he and his business partner Joseph Weintraub (who was also his brother-in-law) opened the Oak Cliff restaurant which boasted two dining rooms (with a seating capacity of 350, suitable for parties and banquets), fine steaks, and, on the weekends, a live band and dancing. Ernest’s wife, Martha, and their son Milton were also part of the family business. When the restaurant opened, there wasn’t much more out there on the “Fort Worth cut-off,” but the place must have been doing something right, because Roth’s lasted for at least 27 years — an eternity in the restaurant business. It seems to have remained a popular Oak Cliff dining destination until it closed around 1967.

*

The real story, though, is the Roth family, especially Ernest’s mother, Johanna Roth, and even more especially, his older sister, Bertha Weintraub.

Johanna Rose Roth was born in 1863 in Budapest, where her father served as a member of the King’s Guard for Emperor Franz Josef. She and her husband and young children came to the United States about 1906 and, by 1913, eventually made their way to San Antonio. In the ’40s and ’50s she traveled by airplane back and forth between San Antonio and Dallas, visiting her five children and their families — she was known to the airlines as one of their most frequent customers (and one of their oldest). She died in Dallas in 1956 at the age of 92.

Johanna’s daughter Bertha Roth Weintraub had a very interesting life. She too was born in Hungary — in 1890. After her husband Joe’s death in the mid ’40s, a regular at her brother’s restaurant, Abe Weinstein — big-time entertainment promoter and burlesque club empresario — offered Bertha a job as cashier at the Colony Club, his “classy” burlesque nightclub located across from the Adolphus. She accepted and, amazingly, worked there for 28 years, retiring only when the club closed in 1972 — when she was 82 years old! It sounds like she led a full life, which took her from Budapest to New York to San Francisco to San Antonio to Austin and to Dallas; she bluffed her way into a job as a dress designer, ran a boarding house in a house once owned by former Texas governor James Hogg, hobnobbed with Zsa Zsa Gabor and Liberace, was a friend of Candy Barr, and, as a child, was consoled by the queen of Hungary. She died in Dallas in 1997, a week and a half before her 107th birthday. (The story Larry Powell wrote about her in The Dallas Morning News — “Aunt Bertha’s Book Filled With 97 Years of Memories” (DMN, Nov. 17, 1987) — is very entertaining and well worth tracking down in the News archives.)

I feel certain that the extended Roth family found themselves entertained by quite a few unexpected stories around holiday dinner tables!

***

Sources & Notes

Matchbook cover (top image) is from the George W. Cook Dallas/Texas Image Collection, DeGolyer Library, Central University Libraries, Southern Methodist University; more info is here.

Photo of Bertha Weintraub is from The Texas Jewish Post (Feb. 15, 1990), via the Portal to Texas History, here.

*

Copyright © 2017 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

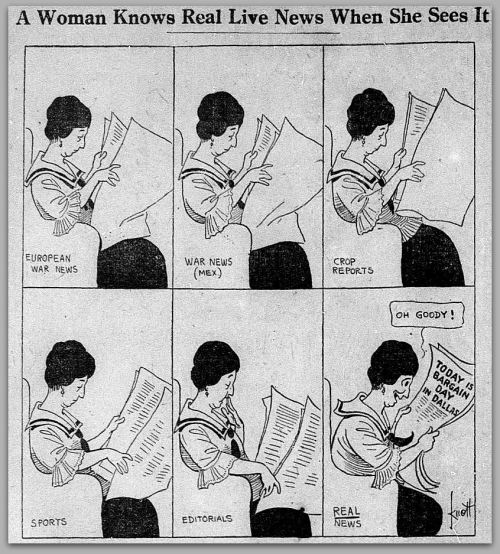

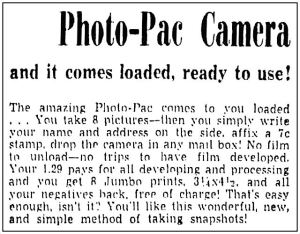

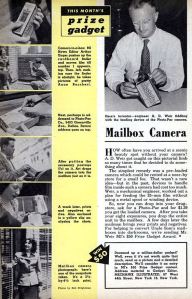

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 16, 1949

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 16, 1949

Mary Roberts Wilson (1914-2001)

Mary Roberts Wilson (1914-2001)

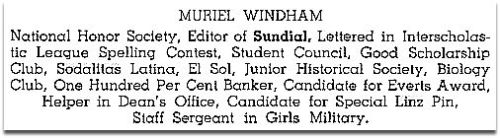

Muriel,

Muriel,

Senior, over-achiever — 1944 yearbook

Senior, over-achiever — 1944 yearbook