Peruna, waiting for the Mustangs to score (photo: SMU)

Peruna, waiting for the Mustangs to score (photo: SMU)

by Paula Bosse

On October 30, 1934, shortly before midnight, Peruna, the 28-inch-tall little black Shetland pony mascot of the Southern Methodist University Mustangs, somehow liberated himself from his stable and wandered across campus and out into the intersection of Mockingbird and Airline where he was, sadly, struck by a hit-and-run driver and died soon after. As the newspaper account noted the next day, when the tragic accident occurred, “He was wearing a bridle of Red and Blue, the Mustang colors.”

Peruna had been the football team’s mascot for only two years, but he was an immensely popular attraction, and he was treated as something of a celebrity wherever he appeared, both at home and when traveling with the football team and the Mustang band. He did things most horses didn’t do, like ride in taxi cabs and sashay though hotel lobbies. Crowds at football games loved watching the little horse race across the field — even the ardent supporters of the opposing teams were charmed by him. And he was, of course, much loved at SMU; his death was a hard blow to the student body.

When he was buried at Ownby Stadium, the band played the usually rousing fight song as a mournful dirge, and the flags on campus flew at half mast.

I’m an animal lover, and stories about the demise of animals are not things I normally find entertaining, especially when phrases like “the midget pony,” “the wee mascot,” “the stout-hearted little mascot,” and “the midget wonder horse” are constantly (and effectively) used by journalists to tug at the readers’ heart-strings. But the Peruna obituary/funeral coverage that was printed in The Dallas Morning News is so wonderfully and ridiculously over-the-top that that one yearns to know who wrote the uncredited story. I have created a little scenario in my head in which the writer had been (and I apologize…) “saddled” with writing a story about a horse’s funeral, but instead of handing it in the pedestrian short-and-vaguely-moving report that was expected, he decided — to hell with it — that he would just go full-throttle and produce the most outrageously grief-stricken story ever written about the untimely death of a college mascot. After what one assumes was the downing of much whiskey and much chuckling to himself (I suspect this was written by a sportswriter), a 500-word obit ran on Nov. 1, 1934:

CO-EDS AND GRID STARS SOB AS PERUNA IS BURIED

(The Dallas Morning News, Nov. 1, 1934)

In sight of the very gridiron on which he pranced to lasting fame, Peruna, stout-hearted little mascot of the Southern Methodist University Mustangs, was laid to rest Wednesday afternoon.

As co-eds sobbed openly and hardened football heroes found difficulty in brushing back the tears, the body of the diminutive pony was lowered into its grave in the shadow of Ownby Oval. His coffin was draped in red and blue, the school colors, and a huge M, the Mustang emblem, graced the top of the casket.

Across the way, on the campus of the big university itself, the flag fluttered at half mast. The school band, looking noticeably bare without Peruna prancing about, playing “Peruna,” the varsity song, in the tempo of a dirge. Hundreds of heads were bowed when the strains of the alma mater, “Varsity,” offered a final tribute to the wee mascot.

Peruna’s career was as colorful as that of the team he represented. Given to the school in November, 1932, by T. R. Jones, loyal Mustang supporter, the midget horse immediately became the constant companion of the team on its journeys from one side of the continent to the other.

Only last week Peruna was feted in New York, parading through the lobbies of the city’s swankiest hotels, whose clerks sniff haughtily at the thought of a dog or a cat entering the sacred portals of their hostelries….

In was in Shreveport where he slipped and cut his leg as he started to Centenary Stadium in a taxicab. His wound was stitched, and the faithful little animal pranced proudly with the band during the between-halves parade.

But Peruna prances no more. And if the music of Bob Goodrich and his Mustang band at Austin Saturday fails by a scant margin of being at its peppiest, it will be because the band has dedicated every tune on that day to the memory of its best friend.

That must have been fun to write.

The year following Peruna’s demise, the Rotunda — SMU’s yearbook — featured a two-page illustrated spread “Dedicated to the famous Mascot of the Mustangs … ‘Peruna.'”

See Peruna’s very, very sweet memorial statue on the SMU campus here.

The loss of Peruna left the Mustangs without a mascot. Peruna’s son was proffered as a replacement, but even though “Little Peruna had been dressed in its father’s blanket and was prepared to give its all for SMU,” the school declined to bring Peruna fils on board. A successor — Peruna II — was eventually appointed, the first of many over the past eighty years. We’re now up to, I believe, Peruna IX, and the little stallion is still as popular as ever. May the “stout-hearted little mascot” continue to prance proudly for the SMU Mustangs.

1939 Peruna (SMU Rotunda)

1939 Peruna (SMU Rotunda)

1960 Peruna (SMU Rotunda)

1960 Peruna (SMU Rotunda)

***

Sources & Notes

Top photo from the 1933 SMU yearbook, The Rotunda. The two-page spread is from the 1935 Rotunda.

For an idea of what the area looked like at the time of Peruna’s terrible midnight accident — large open fields to the north and east of the campus, and, to the south, a probably dimly-lit Mockingbird Lane — here is a detail from a 1930 aerial map from the Edwin J. Foscue Map Library at Southern Methodist University (the full map can be seen here):

(click for larger image)

(click for larger image)

Check out these articles in the Dallas Morning News archives:

- “Car Kills Peruna Back From Victory Over New Yorkers; SMU Mascot Known To Over Half Nation, Dies With Bridle On” (DMN, Oct. 31, 1934)

- “Co-Eds and Grid Stars Sob As Peruna Is Buried” (DMN, Nov. 1, 1934)

- “Grieving Mustangs Won’t Take Son of Peruna for Mascot” (DMN, Nov. 11, 1934)

Peruna on Wikipedia, here.

If you really want to know about Peruna, though, you need to go to the horse’s mouth — his page on the SMU website, here.

Read about the Peruna monument by Dallas artist Michael G. Owen, Jr. which was dedicated on the SMU campus in 1937, here.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

Oh, the Fifties… (click for larger image) (DeGolyer Library, SMU)

Oh, the Fifties… (click for larger image) (DeGolyer Library, SMU) I love these girls’ faces. And hair! (click for larger image)

I love these girls’ faces. And hair! (click for larger image) The Big Men on Campus appear to be enjoying the attention.

The Big Men on Campus appear to be enjoying the attention. That print is kind of … busy. Is it a cowboy motif? Are those horses? Is that Peruna?!

That print is kind of … busy. Is it a cowboy motif? Are those horses? Is that Peruna?!

1939 Peruna (SMU Rotunda)

1939 Peruna (SMU Rotunda) 1960 Peruna (SMU Rotunda)

1960 Peruna (SMU Rotunda)

*

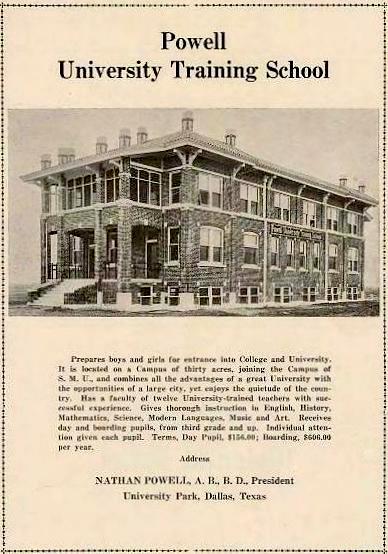

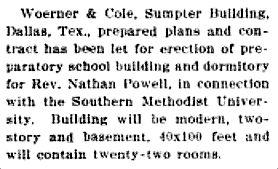

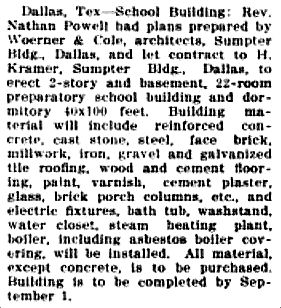

* Both items from the Texas Trade Review & Industrial Record, July 15, 1915

Both items from the Texas Trade Review & Industrial Record, July 15, 1915

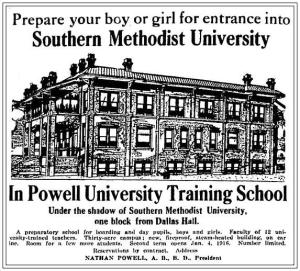

SMU Times, Dec. 18, 1915

SMU Times, Dec. 18, 1915