The Dallas Chapter of “The Women of the Ku Klux Klan” — 1920s

by Paula Bosse

I’ve managed to avoid mention of the Ku Klux Klan since starting this blog a couple of years ago, which is saying something, because the KKK pretty much ruled this city for a good chunk of the 1920s. The Dallas chapter — Klan No. 66 — had more than 13,000 men as members; it was one of the largest chapters in the nation (by some accounts, THE largest chapter). Members included politicians, judges, and law enforcement officials. But what of the Klan-leaning ladies who were not allowed to join? Before I plunge into that, let’s look at what’s going on in this weird, be-robed group shot, a photo taken around 1924 in Ferris Plaza with poor Union Station as a backdrop. (Click these for much larger images.)

**

In the early 1920s, women — who had led the temperance movement and whom had recently been given the right to vote — began to form groups that tackled social issues. Some of these groups espoused the same general rhetoric as the KKK. One of these groups was formed in Dallas in 1922 — the “American Women” group was the brainchild of three women, including Alma B. Cloud, who appears to have been only 21 years old. One of the other founders was her partner in a short-lived ladies’ clothing boutique. Cloud immediately hit the lecture circuit, giving free lectures on “Americanism” to (white Protestant) women around Texas.

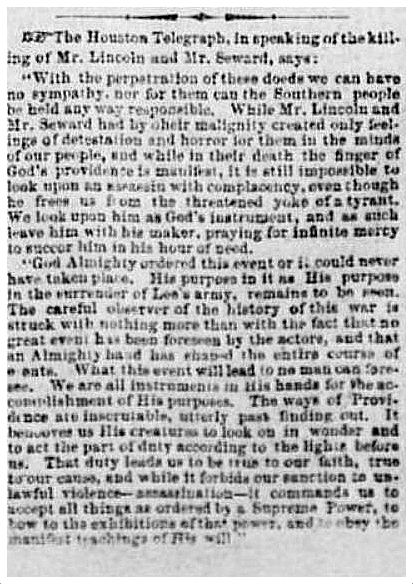

Taylor Daily Press, Aug. 22, 1922

Taylor Daily Press, Aug. 22, 1922

By the following summer, the male leadership of the Klan allowed a “Women of the Ku Klux Klan” to be created; its national headquarters was in Little Rock.

They were not officially part of the KKK but were, in theory, a separate entity. While not, perhaps, as outwardly extreme as their male counterparts, they were certainly as virulently racist and intolerant. They might not have been lynching people and threatening violence, but they were busy pushing their exclusionary, white supremacy agenda. And both the men and the women liked to dress up in white robes and hoods. Here’s what the women looked like when they added masks to the ensemble (not Dallas — location of photo unknown).

Several of the independent women’s groups founded previously were happily absorbed by the WKKK — including Miss A. B. Cloud’s group. In fact, Miss Cloud became the leader of the Dallas chapter. The “Klaliff.” The headquarters for this group — which campaigned for “progressive morality”– was in a little space on North Harwood.

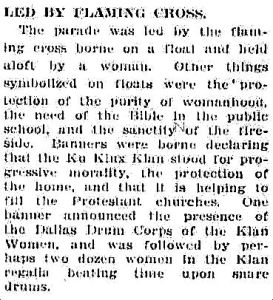

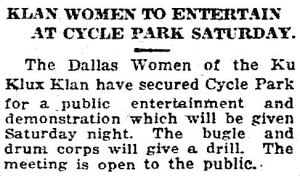

1924 seems to have been the big year for both the KKK and the WKKK. The women found themselves at lots of parades with burning crosses and other … “functions” — so why not form a drum corps? A few clippings. (Click for larger images.)

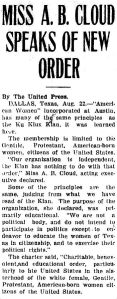

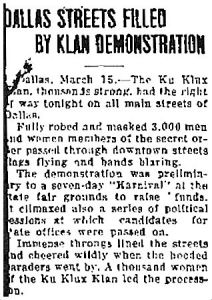

Amarillo Globe-Times, March 16, 1924

Amarillo Globe-Times, March 16, 1924

McKinney Courier-Gazette, Nov. 12,1924

McKinney Courier-Gazette, Nov. 12,1924

By 1926, the KKK was starting to lose its power, and the fear and intimidation they had instilled in much of the public began to wane. The (men’s) KKK had had to downsize and move into the women’s headquarters, and their candidates began losing elections. Even worse, you know things were getting bad if someone was suing the KKK for delinquent robe-payment!

KU KLUX KLAN WOMEN SUED FOR ROBES BILL: Suit for $4,463.80 was filed in the Forty-Fourth District Court on Friday afternoon by John F. Pruitt against the Women of the Ku Klux Klan, Inc. The petition alleges that the plaintiff sold the defendant, a corporation, 6,000 robes at $2.50 each during the two years preceding the filing of the suit, for which the defendant agreed to pay $15,000 to the plaintiff. It is alleged that $4,463.80 remains unpaid. (DMN, Nov. 28, 1925)

The power once exerted by the Ku Klux Klan had diminished greatly by the end of the 1920s, and while the Klan has never disappeared completely, it will never again reach the heights it had attained in the 1920s.

Whatever happened to Miss A. B. Cloud? After having been ousted from her “imperial” position (for reasons I don’t really care enough about to investigate), she had a few sales jobs and eventually began to present motivational sales talks. There was an Alma B. Cloud in California who was mentioned in several news stories from the 1930s — she presented motivational lectures to students on how best to plan their future adult lives. Um, yes. I’m not 100% sure this was the same A. B. Cloud who was the former WKKK gal from Big D, but it seems likely. I wonder what those students would have thought had they known of her pointy-hooded past?

***

Sources & Notes

Links-a-plenty.

Top photo is titled “Ku Klux Klan Women’s Drum Corps Dallas in Front of Union Station,” taken by Frank Rogers; it is from the George W. Cook Dallas/Texas Image Collection, DeGolyer Library, Central University Libraries, Southern Methodist University — it can be accessed here. I have manipulated the color.

Women of the Ku Klux Klan letterhead comes from the Women of the Ku Klux Klan Collection, Archives and Special Collections, University of Mississippi Libraries; the collection can be accessed here.

The photo of the masked WKKK women is all over the internet — I don’t know its original source or any details behind it, but it’s creepy.

“Women of the Ku Klux Klan” on Wikipedia, is here.

“Women of the Klan: Racism and Gender in the 1920s” by Kathleen M. Blee, is here.

“Charity by Day, Punishment by Night: The Ku Klux Klan in Fort Worth” — from the great FW history blog Hometown by Handlebar — is here.

And, probably best of all, the Dallas Morning News article “At Its Peak, Ku Klux Klan Gripped Dallas,” by the wonderful and much-missed Bryan Woolley, can be read here. This article contains facts and figures, describes the sort of “madness of crowds” atmosphere in the city at the time, and details some of the horrible atrocities committed by the KKK in Dallas. Woolley cites historian Darwin Payne’s assertion that if one considered every adult man in Dallas who would have been eligible to have joined the Klan (this excludes, of course, those of African-American, Hispanic, Asian, Catholic, or Jewish descent), one in three of them was a member of the Dallas chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. ONE IN THREE.

A few short mentions of the Dallas WKKK have been compiled here.

UPDATE: For a look at racism in modern Dallas, watch the half-hour film “Hate Mail,” made in 1992 by Mark Birnbaum and Bart Weiss, here. It includes interviews with several prominent Dallasites, as well as interviews with a couple of Klan leaders.

Click pictures and clippings to see larger images.

*

Copyright © 2016 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

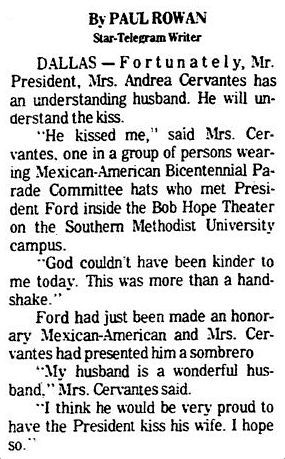

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 25, 1972

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 25, 1972

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Sept. 14, 1975

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Sept. 14, 1975

Greenwood Cemetery, Dallas (photo: David N. Lotz)

Greenwood Cemetery, Dallas (photo: David N. Lotz)