Snag Boat Dallas — 1893

Snag Boat Dallas of Dallas, Trinity River

Snag Boat Dallas of Dallas, Trinity River

by Paula Bosse

“Snagboat.” It’s a great word. And if you’ve taken even a glancing look into the history of the Trinity River, you’ve probably come across it. What is it? According to the Wikipedia entry, it is “a river boat, resembling a barge with superstructure for crew accommodations, and deck-mounted cranes and hoists for removing snags and other obstructions from rivers and other shallow waterways.” If you’re from Dallas, “shallow waterway” will immediately bring to mind our very own Trinity River, which, unless it’s flooding, you probably rarely even think of as being an actual river. But Dallas money-men have tried their damnedest for what seems like EVER to make the Trinity do what they wanted it to do.

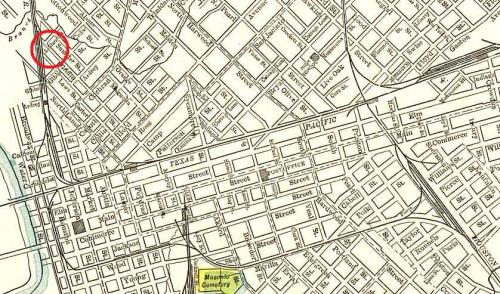

In the late 19th century, a group of Dallas businessmen organized the Trinity River Navigation and Improvement Company and began to sink large sums of money into it. The goal was to make the Trinity navigable for large boats between the Gulf of Mexico and Dallas. They knew that if they could open this waterway to vessels carrying all manner of freight that they could make a lot of money. A lot.

In order to make the Trinity navigable, it first had to be cleared of all sorts of impassable debris in it, on it, over it, and along it. The stretch of the river around the soon-to-be inland port of Dallas was particularly snarled with all sorts of things making passage of large boats through its waters impossible. A snagboat was needed, and construction on the Snag Boat Dallas of Dallas began in November of 1892.

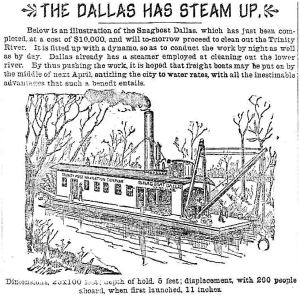

Dallas Morning News, Nov. 26, 1892

Dallas Morning News, Nov. 26, 1892

The construction of the boat was followed closely in the Texas papers, and giddy ads/editorials like this one were filling the pages of Dallas newspapers.

DMN, Jan. 15, 1893

DMN, Jan. 15, 1893

“Water rates” — charges for freight shipped via boat — were lower than the rates charged by railroads. Were the Trinity able to support freight traffic, this new competition would mean that railroads would lower their rates, and the savings for manufacturers and builders would be substantial. As a result, manufacturing and building in the city would boom, and before you knew it, Dallas would become “the greatest city on Earth in the South”!

A few days before the official launch of the boat, reporters, businessmen, and the public were invited to a preview. An interesting account in The Galveston Daily News described the boat’s machinery (which included a “liquid battering ram”) and took the reader on a tour of the crew’s quarters (which had separate sleeping and dining areas for black and white crew members, per the “Separate Coach Law” of 1891).

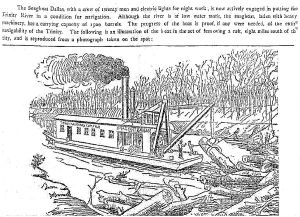

Galveston Daily News, Feb. 19, 1893

Galveston Daily News, Feb. 19, 1893

The boat began its snagging work in February, 1893, and, in order to keep readers abreast of all Snag Boat Dallas developments, there were almost daily updates on its progress in the newspapers, and (in lieu of photographs) Dallas Morning News illustrators provided scenes of the boat’s important work.

The celebrity snagboat succeeded in clearing the debris, and in May, 1893, the steamer H. A. Harvey, Jr. arrived in Dallas, having, yes, navigated the Trinity River from the Gulf, even though it had faced two months’ worth of difficulties along the way (problematic water levels, low bridges which had to be dismantled in order for it to pass under, underwater impediments which had to be dynamited into oblivion, etc.). When it finally pulled into Dallas — accompanied by the hard-working snagboat that had paved its way — the city shut down and had a massive celebration. The Dallas Morning News went so far as to print several of its pages in red ink (!). This proof that the Trinity River was, in fact, navigable, meant that the city was on the cusp on becoming “the greatest city in the South.” The DMN (which was not shy in its almost rabid boosterism of this project) published an editorial for those Dallasites who might “not fully comprehend” the significance of why they were celebrating.

Dallas would become an important inland port. “It can be done.”

Except that we know that it couldn’t be done. Too many other natural forces were working against the Trinity River entrepreneurs. The Harvey and the snagboat didn’t actually do much after that tumultuous reception in 1893. Sure, they moved some small loads back and forth along the Dallas stretch of the river, but that grand vision of taming the Trinity never came to pass. Even now, more than 120 years later, it still has yet to happen. Dallas has done pretty well without the Trinity River being truly navigable, but people can’t seem to stop trying to somehow monetize it. It’s probably time we just appreciated our little section of the Trinity River for what it is: a little trickle of a river that has (so far) survived everything we’ve tried to do to it in the name of “progress.”

*

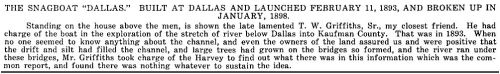

For closure, snagboat fans: the hard-working little Dallas had an ignominious end. It was tied to an old pier and left to rot on the water before it was eventually cannibalized and slowly picked apart. Its end came in January of 1898 when it was finally “broken up.”

DMN, May 28, 1897

DMN, May 28, 1897

RIP, Snag Boat Dallas of Dallas — we hardly knew ye.

*

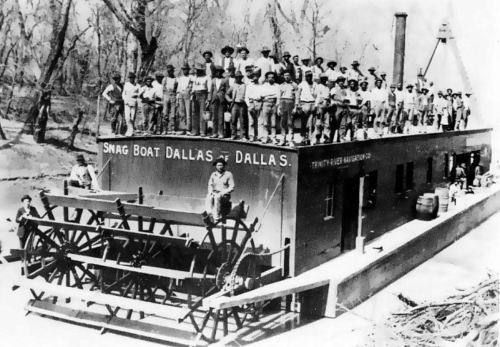

The Harvey (which quietly left town when it was sold to a Louisiana company in 1898) has gotten the lion’s share of the historical attention, but the snagboat is the one that did all the work. Here are two more photos of the Dallas and its crew taking a break from snagging to pose for posterity.

The photo below shows just what the crew of the snagboat was up against. The caption was written by C. A. Keating, president of the Trinity River Navigation Company.

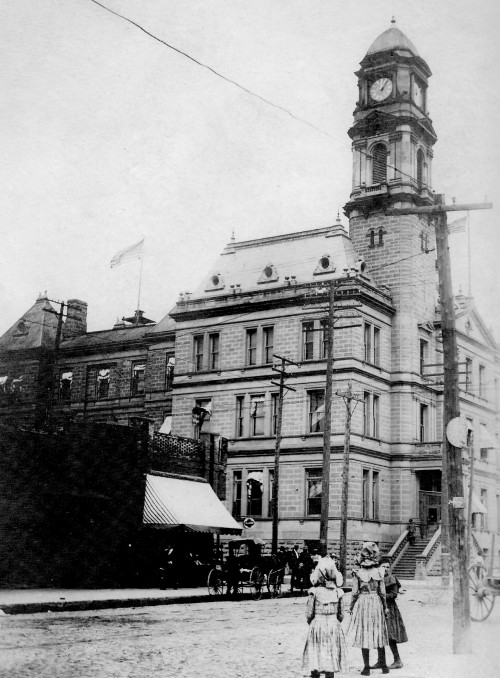

And, finally, what prompted me to find out more about the snagboat in the first place: this ad for the Dallas Lithograph Company from the 1893 city directory. It featured an illustration of a little boat chugging along on the idyllic (and blissfully snag-free) Trinity River, with the Old Red Courthouse in the background and a little tent pitched on the bank. I wasn’t all that familiar with snagboats, but that’s what I thought it looked like. I’m sure it’s supposed to be something grander, but I’ll think of it as a snagboat anyway.

***

Sources & Notes

I came across the top photo (which is from the archives of the Dallas Public Library) on the web page for the 99% Invisible podcast, here. I was so enthralled with the pictures on this page that I didn’t even realize until just now that there was a podcast to listen to, called “The Port of Dallas” — about this very topic! Listen to it at the top of the page — it’s very entertaining. I think Julia Barton and I were separated at birth!

There are lots of other photos on that page, including a photo of the H. A. Harvey, Jr. and a photo showing what the Dallas Morning News looked like printed in red.

Second photo of the Snag Boat Dallas is from the DFW Urban Wildlife blog, here. More great photos there!

The final photo of the Dallas and the photo’s caption are from C. A. Keating’s autobiography, Keating and Forbes Families and Reminiscences of C. A. Keating (Dallas: self-published, 1920).

All other clippings, as noted.

To read about how people have tried and tried and tried over the years to make the Trinity River do what they wanted it to do — and failed — read the article “Navigating the Trinity, A Dream That Endured for 130 Years” by Jackie McElhaney (Legacies, Spring 1991), here.

UPDATE: I swear I was completely unaware of Julia Barton’s podcast about the “Port of Dallas” when I wrote this post, but I’m happy to report there is ALSO a video, from a presentation she did at the TEDxSMU talks in October. Watch it here. (Thanks, for alerting me to that this, Julia — my “internet twin”!)

*

Copyright © 2015 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

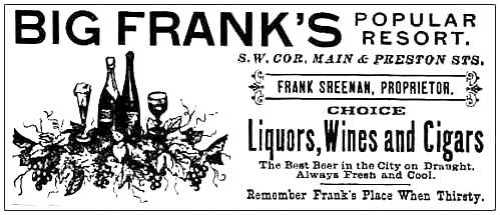

“Remember Frank’s Place When Thirsty”

“Remember Frank’s Place When Thirsty”

via Dallas Public Library

via Dallas Public Library

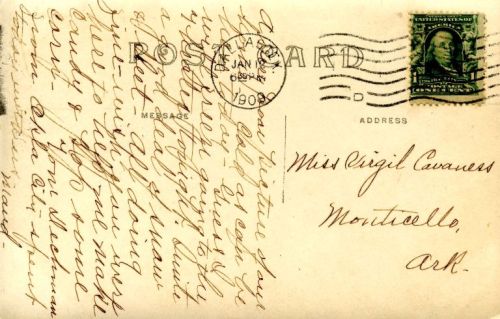

DMN, Sept. 2, 1906

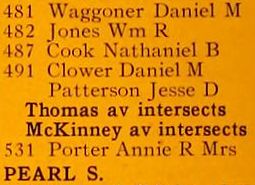

DMN, Sept. 2, 1906 1909 city directory, residents of N. Pearl Street

1909 city directory, residents of N. Pearl Street

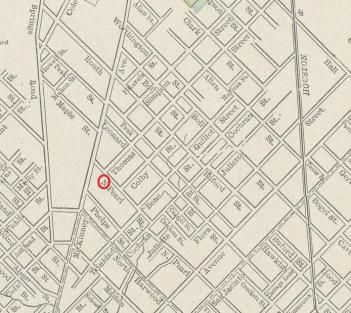

Souvenir Guide to Dallas, 1894

Souvenir Guide to Dallas, 1894 DMN, Aug. 24, 1887

DMN, Aug. 24, 1887 DMN, Oct. 22, 1899

DMN, Oct. 22, 1899

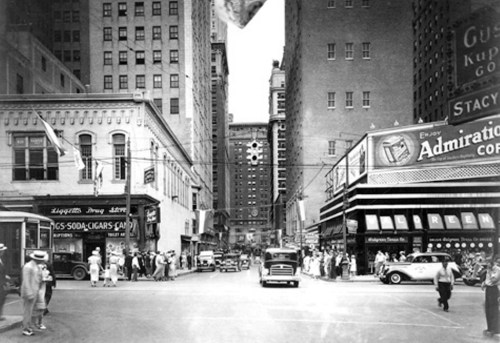

1929

1929