The Mosquito Bar

Relax without fear of being bitten by mosquitoes…

Relax without fear of being bitten by mosquitoes…

by Paula Bosse

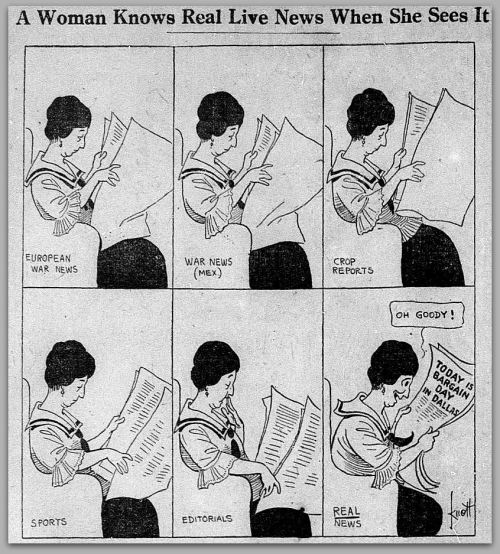

The “mosquito bar” — the human’s defense against blood-thirsty mosquitoes (and other annoying pests) — had its heyday in the US in the second half of the 19th century and the first couple of decades of the 20th century, before screens for windows and doors were commonplace in American homes. They were particularly necessary in the hot and sweaty Southern US states which were routinely plagued with mosquitoes. A typical mosquito bar ad looked like this one from Dallas merchants Sanger Bros. (click ads and clippings to see larger images):

(According to the Inflation Calculator, $1.00 in 1885 money would be worth about $27.00 in today’s money, adjusted for inflation.)

The first Dallas ad I found for mosquito bars was from 1877 — like the clipping above, it is also from a Sanger Bros. ad (in fact, Sanger’s seemed to be mosquito-bar-central for 19th-century Dallas).

Southern Mercury, July 3, 1890

Southern Mercury, July 3, 1890

Mosquito bars were usually draped over beds, canopy-style, but the painting above (“Mosquito Nets” by John Singer Sargent, 1908) shows “personal” net-covered armatures, perfect for genteel ladies to relax inside of and read (while trying to keep cool despite being weighed down by what must have been uncomfortably heavy clothing).

The mesh netting or fine muslin used to drape beds (and cover windows and doors) was generally white or pink, sometimes green. Once inside the canopied beds, the netting was tucked under the mattress in order to seal all potential entry points in the mesh-walled fortress and allow the thankful occupants inside to sleep unmolested by mosquitoes (or other biting and stinging insects).

These bars became fairly standard in hotels and in many homes of the time, but if one could not afford the luxury of sleeping inside one of these things, the sleeper would often resort to rubbing him- or herself with kerosene if they wished to avoid being bitten throughout the night.

Dallas Morning News, Oct. 1, 1910

As much of a godsend as the bars were, they had their problems. The fine material was easily torn, and sometimes the mesh was so tightly knit that ventilation (and breathing!) was not optimal. Also, it was not unusual for them to catch fire — there are numerous newspaper reports of the bars being ignited by candles or gas-burning lamps or by careless or sleepy smokers smoking inside the canopy.

It was apparently a common precaution against midnight thievery for men who stayed in hotels to keep their money in the pockets of their pants and then fold the pants and place them beneath their pillows. The second line of defense was the mosquito netting tucked resolutely under the mattress of their canopied beds. The feeling was that a burglar would have to be pretty stealthy to breech a man’s mosquito bar and steal his pants from under his pillow without waking him. But never underestimate the Big City burglar (click article to see a larger image):

After doors and windows began to be routinely covered with wire screens, the use of mosquito bars in homes and hotels waned, but their use continued in military encampments and hospitals, in recreational camping, and in swampy or tropical areas where the transmission of diseases like malaria and Dengue fever (transmitted by mosquitoes) posed health risks. Wire screens must have been a godsend.

And if you don’t think that the prospect of a night without a mosquito bar (especially in the bayous of Louisiana…) wouldn’t inflame usually calmer heads, here’s a news story from 1910 about a man who shot a co-worker three times at close range because of a heated argument over which of them owned a mosquito bar. And this was in February! Lordy. Talk about your crime of passion. The moral of this story: do not mess with another man’s mosquito bar.

Town Talk (Alexandria, LA), Feb. 22, 1910

*

***

Sources & Notes

The top painting by John Singer Sargent — titled “Mosquito Nets” (1908) — is from the Detroit Institute of Arts; more on the painting can be found here.

Photo of draped bed is from the “Mosquito Net” Wikipedia page, here.

Other clippings and ads as noted. Dallas Herald and Southern Mercury newspaper scans are part of the huge database of scanned historical Texas newspapers found at the Portal to Texas History (to see newspapers, click this link and filter by “Counties,” “Decades,” “Years,” etc. on the left side of the page, or search by keywords at the top).

This post was adapted from a post I wrote for my other (non-Dallas) blog, High Shrink — that post, “The Mosquito Bar,” can be found here (it includes some great additional photographs and illustrations).

*

Copyright © 2017 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.