“There Are Eight Million Stories in the Naked City…” — ca. 1920

by Paula Bosse

The photograph above, by George A. McAfee, shows Ervay Street, looking south from Main, in about 1920. Neiman’s is on the right. I’m not sure what the occasion was (I see special-event bunting….), but the two things that jump out right away are the number of people on the sidewalks and the amount of congestion on the streets. In addition to private automobiles (driven by “automobilists” or “autoists,” as the papers of the day referred to them), the street is also packed with cars standing in the taxi rank (cab stand) at the left, and a long line of hulking streetcars. This busy intersection is jammed to capacity.

The city of Dallas was desperately trying to relieve its traffic problems around this time, and there were numerous articles in the papers addressing the concerns of how to manage the congestion of streets not originally designed to handle motor vehicle traffic. Dallas and Fort Worth were working on similar plans of re-routing traffic patterns and instituting something called “skip stop” wherein streetcars would stop every other block rather than every block. Streetcars, in fact, though convenient and necessary, seemed to cause the most headaches as far as backing up and slowing down traffic, as they were constantly stopping to take on and let off passengers. There was something called a “safety zone” that was being tried at the time. I’m not sure I completely understand it, but it allowed cars to pass streetcars in certain areas while they were stopped.

That traffic is crazy. But, to be perfectly honest, it’s far less interesting than all that human activity — hundreds of people just going about their daily business. It’s always fun to zoom in on these photos, and, below, I’ve broken the original photograph into several little vignettes. I love the people hanging out the Neiman-Marcus windows. And all those newsboys! Not quite as charming was all that overhead clutter of power lines and telephone lines; combined with the street traffic, it makes for a very claustrophobic — if vibrant — downtown street scene. (Click photos for larger images.)

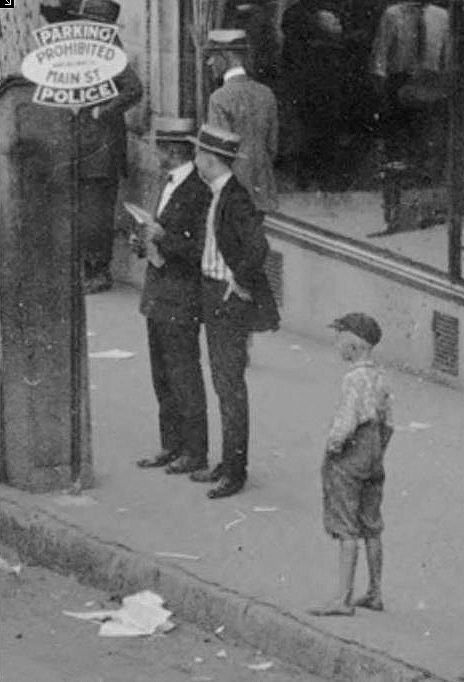

My favorite “hidden” image in the larger photograph. The only moment of calm.

My favorite “hidden” image in the larger photograph. The only moment of calm.

I love this. The woman in front of the Neiman-Marcus plaque looking off into the distance, the display in the store window, the newsboy running down the street, the man in suspenders, the women’s fashions, and all those hats!

I love this. The woman in front of the Neiman-Marcus plaque looking off into the distance, the display in the store window, the newsboy running down the street, the man in suspenders, the women’s fashions, and all those hats!

A barefoot boy and litter everywhere.

A barefoot boy and litter everywhere.

The congestion is pretty bad above the streets, too.

The congestion is pretty bad above the streets, too.

Cabbies, newsboys, and working stiffs.

Cabbies, newsboys, and working stiffs.

I swear there was only one streetcar driver in Dallas, and he looked like this! Those motormen had a definite “look.”

I swear there was only one streetcar driver in Dallas, and he looked like this! Those motormen had a definite “look.”

***

Sources & Notes

Original photograph attributed to George A. McAfee, from the DeGolyer Library, Central University Libraries, Southern Methodist University, accessible here.

For other photos I’ve zoomed in on the details, see here.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

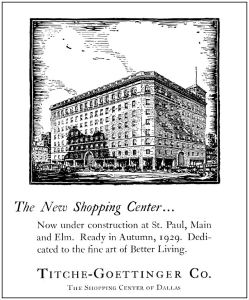

1923

1923

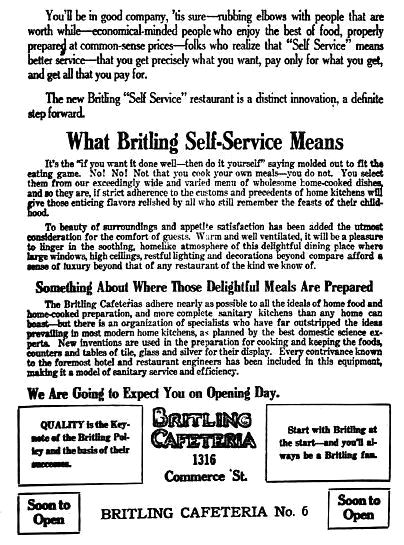

1926

1926