Sam Ventura’s Italian Village, Oak Lawn

by Paula Bosse

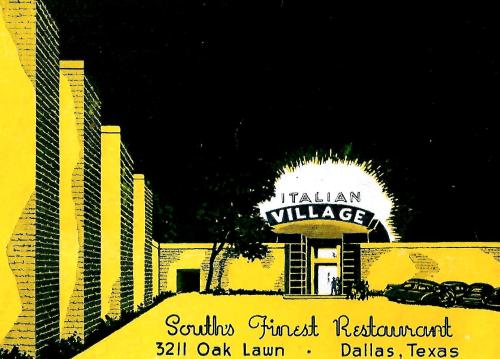

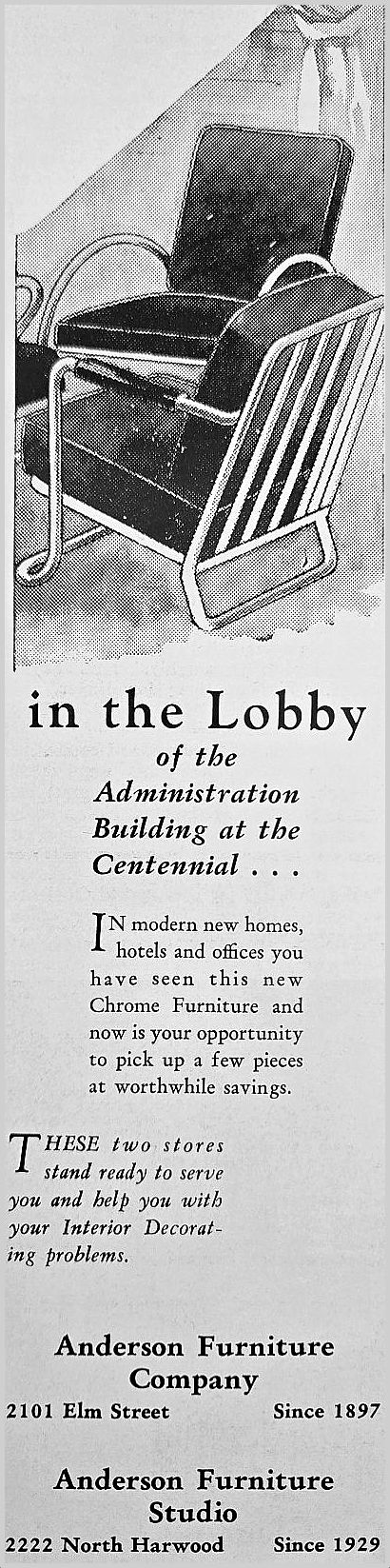

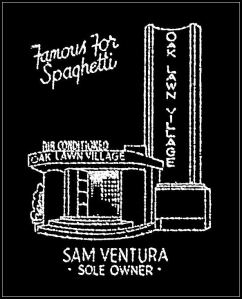

In amongst photos and belongings of my mother’s aunt, I recently came across this wonderful graphic of Oak Lawn’s Italian Village (3211 Oak Lawn, at Hall). It was on the cover of one of those cardboard photo holders which contained photos of diners and club-goers captured by photographers wanting to memorialize celebrants’ special occasions — they would take your photo and you would later purchase prints, which would be tucked inside the souvenir folder. (I don’t recognize any of the people in the photo which was inside — the photo is here.)

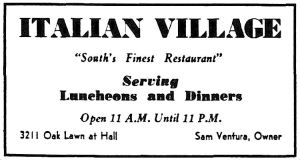

The Italian Village complex (which contained all its various tangential enterprises over he years) was an Oak Lawn fixture for over 45 years — it was apparently still around during my lifetime, but I have no memory of ever seeing it. But by the time I would have been aware of it, things had begun to get a little weird and its profile had definitely dipped. (More on that later.)

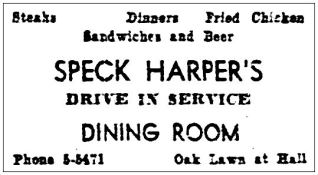

Italian Village began its life in 1934 when Sam Ventura (1907-1997) bought a popular drive-in restaurant in Oak Lawn from a man named Levi F. “Speck” Harper. In Ventura’s obituary in The Dallas Morning News, his wife said: “He bought it from a man named Speck Harper who told him, ‘Give me $250 and my hat, and you’ll never see me again.’ Sam had to go and borrow the money.” (DMN, June 1, 1997) ($250 in today’s money would be about $4,700.)

Not only did $250 start Ventura on a very successful career as a restaurateur, it also assured him ownership of what would quickly become a primo piece of real estate. (Ventura dabbled in real estate and, in 1937, along with fellow restaurant man Sam Lobello, he purchased land at Preston Road and Northwest Highway which would one day become Preston Center.) (It might be worth noting here that Sam Ventura was not affiliated with the very popular Sammy’s restaurants, run by Dallas’ Messina family.)

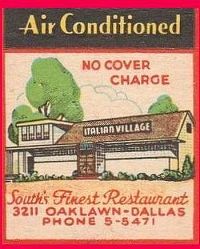

Matchbook, via eBay

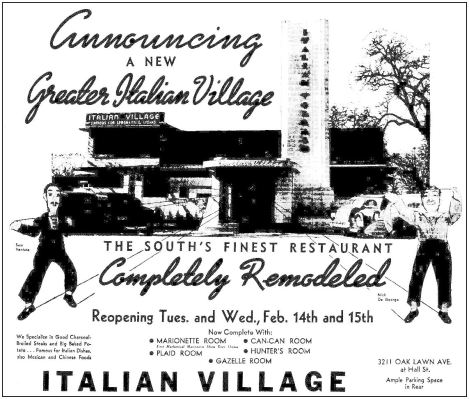

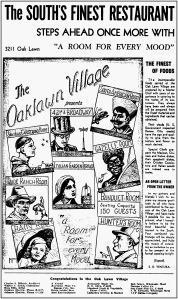

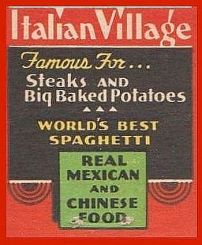

Italian Village — a restaurant which operated for many years as a private club in order to sell liquor — was originally co-owned by brothers-in-law Sam Ventura and Nick DeGeorge (DeGeorge was later married to Ventura’s sister Lucille). By the time the ad below appeared in 1939, the place had been newly remodeled and was on its ninth (!) expansion. There were lots of new “rooms”: the Can-Can Room, the Plaid Room, the Hunter’s Room, the Gazelle Room, and the Marionette Room, the latter of which featured entertainment in the form of a marionette show with puppets made in likenesses of the owners. (All images are larger when clicked.)

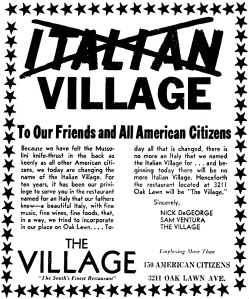

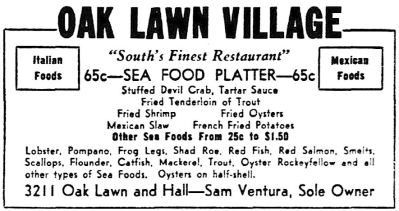

In June, 1940, Italy entered the War in Europe as a member of the Axis forces. As a result, Ventura and DeGeorge immediately asserted their patriotism and their American-ness (both were born in the United States to Italian immigrants) by changing the name of their restaurant: arrivederci, Italian Village, hello, Oak Lawn Village. The owners placed an ad in Dallas newspapers explaining their decision (see ad below) — this made news across the country, garnering both positive national publicity as well as fervent local support.

Not only did the restaurant’s name change in 1940, so did its ownership. Nick DeGeorge and his wife (the sister of Sam Ventura) embarked on a very lengthy, very bitter divorce (newspapers reported that Nick and Lucille were each on their fourth marriages). The result of this marital split spilled over and also caused a business split: Ventura became the sole owner of Italian Oak Lawn Village, and DeGeorge left to start his own (very successful) restaurant career (DeGeorge’s, Town & Country, etc.). Sam announced that he was “sole owner” in a September, 1940 ad. (I hope Nick at least got custody of his mini-me marionette….)

Oak Lawn Village matchbook cover, via Flickr

In June, 1941 yet another remodeling/expansion was announced, with architectural design by longtime friend of Ventura and DeGeorge, Charles Dilbeck, and murals by Russ Ellis. In addition to the Gazelle Room (“for comfort”) and the Hunter’s Room (“for private parties”), there was now the San Juan Capistrano Room (“follow the swallows”), the 42nd & Broadway Room (“for luxury”), the South American Room (“for romance”), the Dude Ranch Room (“where the west begins”), the Rain Room (“for private parties”), the Banquet Room (“seating capacity 150 guests”), and an outdoor Italian Garden Terrace (“beneath the stars”).

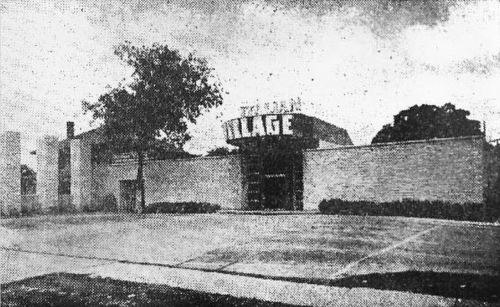

That $20,000 remodel (which would have been equivalent to about $350,000 in today’s money) went up in smoke — literally — in April, 1944, when the restaurant was “virtually destroyed” by fire. Ventura said he would rebuild when war-time government regulations would permit him to do so. At the end of the year he announced that he would build a new restaurant, of shell stone and marble construction, lit in front by decorative tower lights. The new place was built and in full swing — and back with its original name — in the summer of 1945.

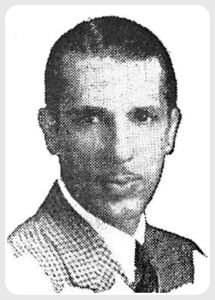

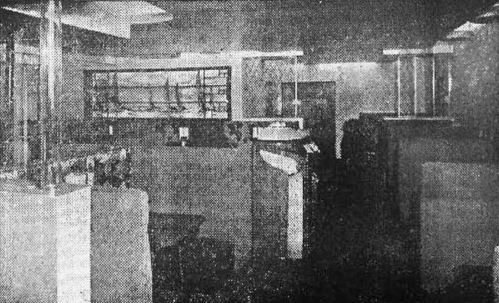

An ad for Dallas’ S. H. Lynch & Co.’s Seeburg Scientific Sound Distribution system appeared in the Aug. 10, 1946 issue of Billboard magazine, showing photos of Sam Ventura, the exterior of the new building, and an interior shot showing a Seeburg jukebox. (See full ad here.)

Sam D. Ventura, 1946 (ad detail, Billboard magazine)

Sam D. Ventura, 1946 (ad detail, Billboard magazine)

Italian Village exterior and interior, 1946 (ad detail, Billboard magazine)

Italian Village exterior and interior, 1946 (ad detail, Billboard magazine)

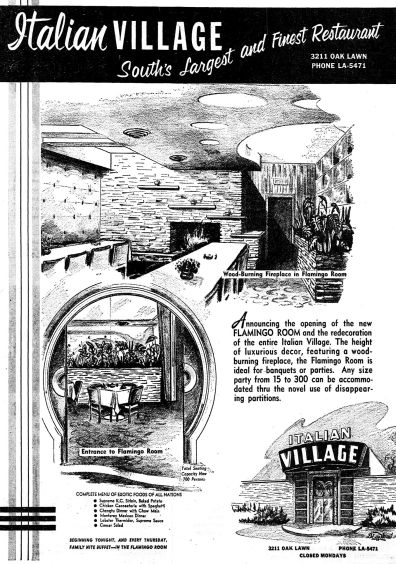

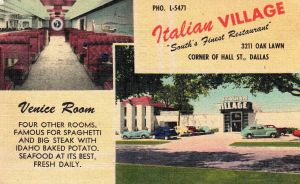

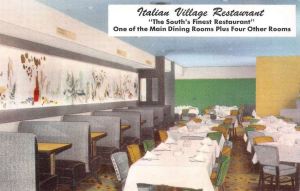

In January, 1951 another remodeling (to the tune of $75,000!) introduced the 300-seat Flamingo Room, which meant the entire Italian Village now had a seating capacity of more than 700 (Ventura had said that the original post-Speck’s restaurant seated only 40 or 50 people). The “modernistic styling” was the work of architect J. N. McCammon.

Front and back of 1955 menu, via eBay

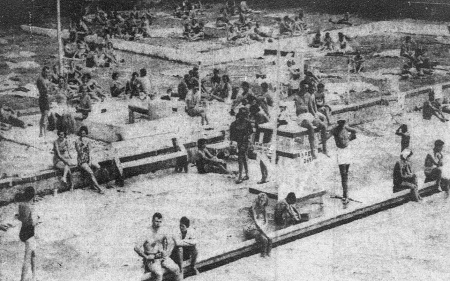

Below, a shot of the Italian Villa’s four odd brick structures seen from across the street (in a screen capture from unrelated January 1955 news footage).

KXAS-NBC 5 News Collection, UNT

KXAS-NBC 5 News Collection, UNT

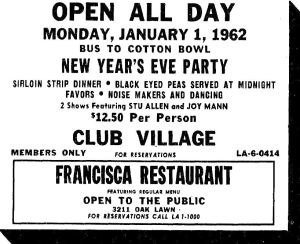

Further changes came to 3211 Oak Lawn in the fall of 1954 with the arrival of the Village Club, which featured live entertainment (including a rotating piano) and shared a kitchen with Italian Village. It was also a “private locker club” with personal liquor lockers available to members to keep their bottles in at a time when it was not legal for restaurants in Dallas to sell liquor-by-the-drink — “set-ups” were sold and the demon alcohol was poured from the member’s stash (or, more likely, from the communal stash).

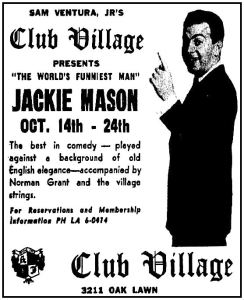

In 1961 there was yet another remodel, which enlarged the club — now called Club Village — and shrank the restaurant. The swanky new club was designed by Charles Dilbeck and had a sort of Olde English theme (and, for some reason, featured a waterfall, a glass cage behind the bar containing live monkeys, and two live flamingos named Lancelot and Guenevere).

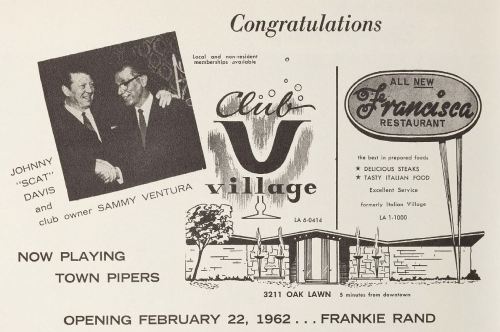

Around this time the (apparently short-lived) Francisca Restaurant appeared.

via eBay

via eBay

1961 also marked the club’s debut on national television, appearing in scenes of the hit show Route 66, which were filmed in November. Below is a screen-capture from the episode “A Long Piece of Mischief,” with the waterfall in the background. (The entire episode, shot around the Mesquite Rodeo, can be watched on YouTube here — the two Club Village scenes begin at the 26:42 and 38:15 marks.)

Route 66 (screen capture) — Nov., 1961

Route 66 (screen capture) — Nov., 1961

In late 1966, Dallas filmmaker Larry Buchanan shot his cult classic Mars Needs Women in various locations all over town. I’m pretty sure one of the very first scenes was shot inside the club, after yet another remodel. (Incidentally, see what the lively neon-ified corner of Oak Lawn and Lemmon, a couple of blocks away, looked like in Buchanan’s film, here.)

Mars Needs Women (screen capture) — 1966

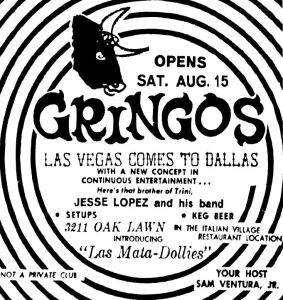

In August, 1964 a new club opened: Gringos (sometimes spelled Gringo’s). This public club, featuring mostly rock bands, was the brainchild of Sam Ventura, Jr. (who said in an interview that he had rather brazenly sprung the whole thing as a big surprise on his father, who had been out of town on a lengthy vacation — luckily, the club was a hit and Sam, Sr. was pleased). Club Village continued as a private club, but from newspaper accounts it seems that the new discotheque displaced the Italian Village and/or Francisca restaurant completely. So now on one side you had the long-running “sophisticated” private club, and on the other side, the “new concept in continuous entertainment,” with its Mexican-themed decor and Watusi-dancing waitresses (“Las Mata-Dollies…”), which catered to a younger set. The Fort Worth Star-Telegram described Gringos thusly:

Newest “port of call” for Dallas revelers on the bistro beat is the just-opened and lavishly-done Gringos Club on Oak Lawn Ave. near the Melrose Hotel and in the location formerly occupied by the Italian Village Restaurant and Village Club. Open to the public, this night time Camelot with Mexican decor features, among other flings, Jesse (brother of Trini) Lopez and his handful of musical consorts on the bandstand and a covey of revealing young handmaidens called “Las Matta-Dollies” [sic], sort of Spanish-type Playboy Bunnies who are worthy of your scrutiny. (Chris Hobson, FWST, Aug. 27, 1964)

In May, 1967, Sam Ventura, Jr. (“Sammy,” who had taken over the family business when Sam, Sr. retired in 1966) declared that Gringos was dead: “There will be absolutely no rock-and-roll in this room anymore. It’s dead. Our whole concept [now] is for sophistication, for adult entertainment” (DMN, May 24, 1967). So adios, Gringos, hello an even bigger Club Village. (In 1968 a club described as a “new” Gringos opened a block away, at 3118 Oak Lawn — it’s unclear whether this was affiliated in any way with the Ventura family.)

In June, 1968, the never-ending improvements, remodelings, and reconfigurings of 3211 Oak Lawn continued with Sammy’s announcement of a new (public) restaurant, the Wood ‘N Rail. This steakhouse featured a revolving “ice bar” (the old revolving piano bar, repurposed), which contained a display of raw meat — from this, customers would choose whichever cut of beef called to them, and before the meat was escorted into the kitchen, the patron would sear his or her initials into it with a “red-hot branding iron.” The restaurant’s slogan was “Personalized Beef.” The unstoppable Club Village continued as a private club and restaurant in the adjoining complex.

1971 began with a fire. The (once) unstoppable Club Village was destroyed. The adjacent Wood ‘N Rail emerged unscathed. So, yes, more remodeling! By 1972, 3211 Oak Lawn boasted three (three!) restaurants at one address: the continuing Wood ‘N Rail (steakhouse), Fisherman’s Cove (seafood), and — hey! — the return of Italian Village. As the ads said: “3 RESTAURANTS UNDER ONE ROOF!”

Also big news in 1971: it finally became legal to order liquor and mixed drinks in bars and restaurants — the whole “private club-membership” thing in order to get around liquor laws was mostly a thing of the past (unless you lived in a dry area of the city…).

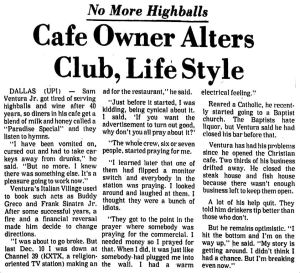

Then, in 1974, things really changed. After a “profound religious conversion,” Sammy Ventura stopped all sales of alcohol and told the TABC he didn’t need or want that ol’ liquor license. This made news around the country.

UPI wire story, Panama City [FL] News Herald, Aug, 1974

UPI wire story, Panama City [FL] News Herald, Aug, 1974

Unsurprisingly, business plummeted. Two of the three restaurants closed. Italian Village continued to limp along, even weathering the introduction of the King’s Village, “Dallas’ first Christian dinner theater.”

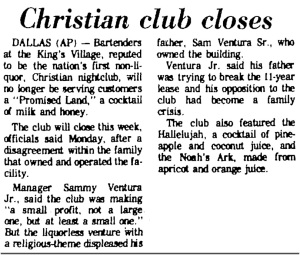

This change in direction of the the 40-plus-year-old family business caused a huge rift between Sammy and his father. Sam, Sr. put his foot down, and The King’s Village (“the nation’s first non-liquor, Christian nightclub”) closed in June, 1977.

AP wire story, Pampa Daily News, June 21, 1977

Oak Lawn’s decades-old Italian Village was no more (although Sammy appears to have opened his own Italian Village restaurant in Richardson’s Spanish Village for a while). The last mention I found of Italian Village was in Feb., 1979:

After 45 years, the Italian Village restaurant has changed to another venture, the Crazy Crab. Sam Ventura opened the Italian Village in 1934 and the last event before the changeover was a surprise birthday party honoring Sam. (DMN, Feb. 23, 1979)

It’s a shame Italian Village’s last incarnation was a mere shadow of its former go-go glory, but it’s almost unbelievable that a restaurant in Dallas was in business for 45 years. Sam Ventura’s $250 gamble in 1934 paid off very, very well.

***

Sources & Notes

Top image is the front cover of a cardstock photo-holder (with linked photo by the Gilbert Studios, 4121 Gaston); collection of Paula Bosse.

All clippings and images are larger when clicked.

*

Copyright © 2018 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.