Nicholas J. Clayton’s Neo-Gothic Ursuline Academy

by Paula Bosse

Over the years, Dallas has been the site of dozens and dozens of beautiful educational campuses, almost none of which still stand — such as the long-gone Victorian-era Ursuline Academy, at St. Joseph and Live Oak streets (near the current site of the Dallas Theological Seminary). The buildings, which began construction in 1882, were designed by the Catholic church’s favorite architect in Texas, Nicholas J. Clayton of Galveston. Such a beautiful building in Dallas? It must be demolished!

Six Ursuline Sisters, sent to Dallas from Galveston, established their academy in 1874 in this poorly insulated four-room building (which remained on the Ursuline grounds until its demolition in 1949). When they opened the school, under tremendous hardship, they had only seven students. But the school grew in size and reputation, and they were an academic fixture in East Dallas for 76 years. In 1950 the Sisters moved to their sprawling North Dallas location in Preston Hollow where it continues to be one of the state’s top girls’ prep schools. After 140 years of educating young women, Ursuline Academy is the oldest continuously operating school in the city of Dallas.

Construction took a long time. (ca. 1894)

Construction took a long time. (ca. 1894)

When Latin cost extra. (1894) (Click for larger image.)

When Latin cost extra. (1894) (Click for larger image.)

It even had a white picket fence. (ca. 1906)

It even had a white picket fence. (ca. 1906)

After a year and a half on the market, the land was sold in 1949 for approximately $500,000 to Beard & Stone Electric Company (a company that sold and serviced automotive electric equipment). The property was bounded by Live Oak, Haskell, Bryan, and St. Joseph — acreage that would certainly go for a lot more these days (according to the handy Inflation Calculator, half a million dollars in 1949 would be the equivalent in today’s money of about five million dollars). A small cemetery was on the grounds, in which the academy’s first chaplain and “more than 40 members of the Ursuline order” had been buried. I’m not sure how these things are done, but the cemetery was moved.

From a November, 1949 Dallas Morning News article on the vacated buildings’ demolition:

A workman applied a crowbar to a high window casing of the old convent and remarked: “I sure hate to wreck this one. It’s like disposing of an old friend. My father was just a kid when this building was built in 1883.” (DMN, Nov. 13, 1949)

And one of East Dallas’ oldest and most spectacular landmarks was gone forever. Looking at these photographs, it’s hard to believe it ever existed at all.

*

Where was it? In Old East Dallas, bounded by Live Oak, Haskell, Bryan, and St. Joseph. See the scale of the property in the 1922 Sanborn map, here (once there, click for full-size map). Want to know what the same view as above looks like today? If you must, click here.

***

Sources & Notes

Photo of the school’s first building is from the Ursuline Academy of Dallas website here. A short description of the early days of hardship faced by the Sisters upon their arrival in Dallas is here.

The photograph, mid-construction, is by Clifton Church, from his book Dallas, Texas Through a Camera (Dallas, 1894).

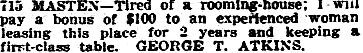

1894 ad is from The Souvenir Guide of Dallas (Dallas, 1894).

1912 text is from an article by Lewis N. Hale on Texas schools which appeared in Texas Magazine (Houston, 1912).

Aerial photograph from the George W. Cook Dallas/Texas Image Collection, DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University, here. Bottom image also from the Cook Collection, here.

Examples of buildings designed by Nicholas J. Clayton can be seen here (be still my heart!).

DMN quote from the article “Crews Begin Wrecking Old Ursuline Academy” by William H. Smith (DMN, Nov. 13, 1949).

Another great photo of the building is in another Flashback Dallas post — “On the Grounds of the Ursuline Academy and Convent” — here.

Many of the images are larger when clicked.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

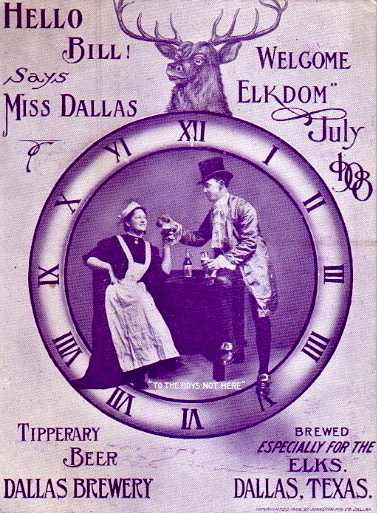

1908

1908

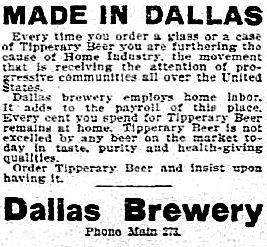

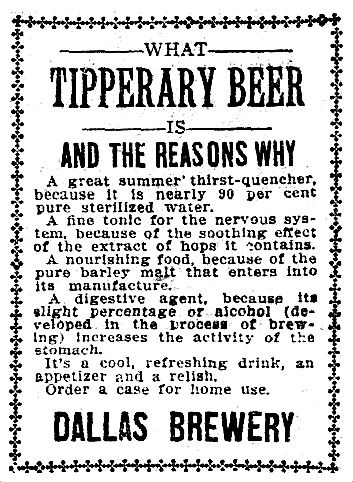

Dallas Morning News, July 18, 1906

Dallas Morning News, July 18, 1906 DMN, Sept. 1, 1907

DMN, Sept. 1, 1907

Change is imminent. (Dallas Morning News, July 26, 1900)

Change is imminent. (Dallas Morning News, July 26, 1900)

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 21, 1913

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 21, 1913 Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Feb. 17, 1917

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Feb. 17, 1917

DMN, June 15, 1922

DMN, June 15, 1922

Southern Mercury, Oct. 9, 1888 (detail)

Southern Mercury, Oct. 9, 1888 (detail)

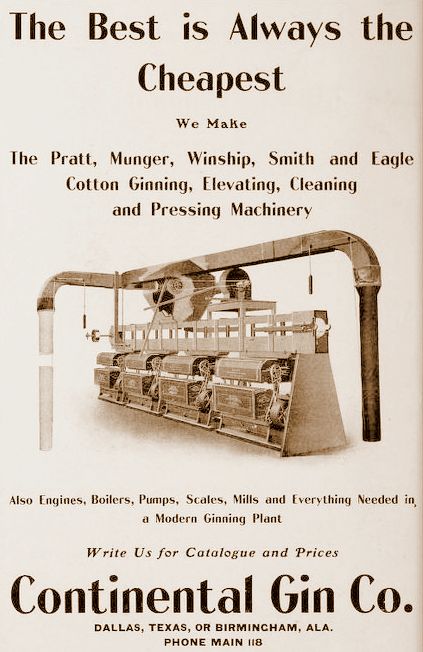

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 12, 1888

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 12, 1888 DMN, June 3, 1888

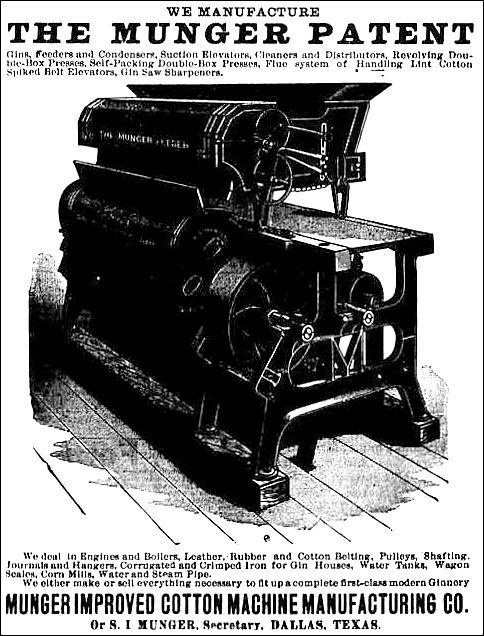

DMN, June 3, 1888  DMN, Aug. 8, 1897

DMN, Aug. 8, 1897 DMN, Oct. 20, 1918

DMN, Oct. 20, 1918 DMN, Aug. 9, 1920

DMN, Aug. 9, 1920