Black Troops from Dallas, Off to the Great War

by Paula Bosse

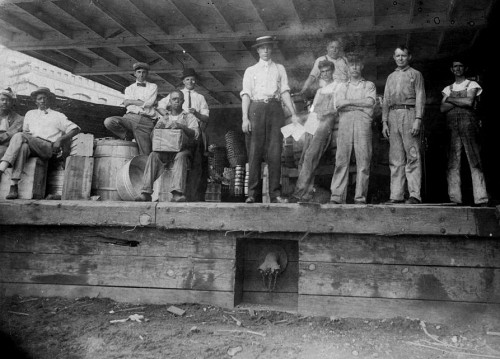

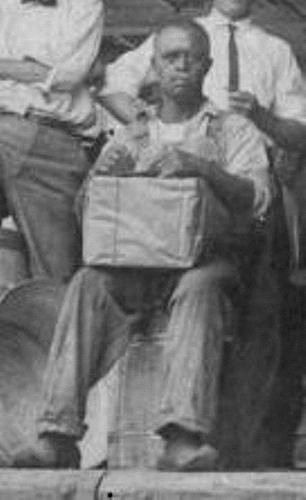

Above is a photo from the National Archives, described only as “Negro recruits having a turkey dinner just before leaving for a training camp. Dallas, Texas.” At the bottom right is the seal of Dallas photographer John J. Johnson who had worked for The Dallas Morning News as a photographer before World War I but was apparently working in a commissioned or freelance capacity here. The photo was taken on June 11, 1918, but the location is not known.

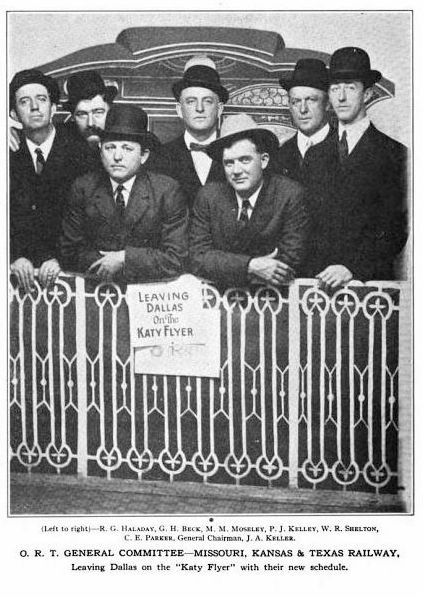

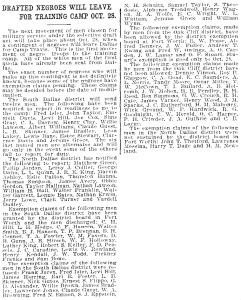

Eight months earlier, Black draftees left Dallas for the first time — they were headed to Camp Travis in San Antonio. (Click articles for larger images.)

Dallas Morning News, Oct. 18, 1917

Dallas Morning News, Oct. 18, 1917

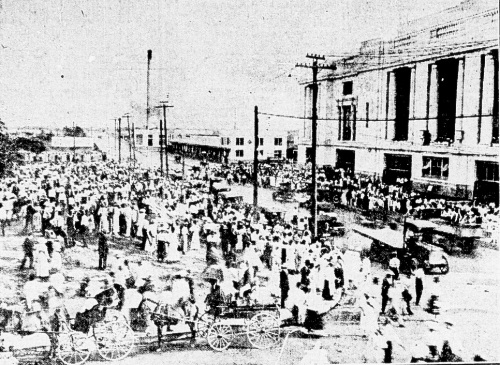

Much larger contingents of Black men left for training camp in the summer of 1918: more than 500 men left from Dallas and more than 200 from Fort Worth at the end of July. The photo below appeared in The Dallas Morning News under the headline “Scene at Union Station Last Night, When 500 Negroes Left for Camp.” (This photo was taken by John J. Johnson, the same photographer who took the photo at the top of this post.)

Photo and caption from the DMN, July 31, 1918

Photo and caption from the DMN, July 31, 1918

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, July 31, 1918

There was a sizable number of Black soldiers at Camp Bowie in Fort Worth, and many of the reports from Fort Worth on the training of the “negro troops” are hard to read. I don’t think of myself as naive, but the blatant racism that was absolutely everywhere in the mainstream press at the time is stunning. Even when attempting to be complimentary, you see things like this:

If you imagine that the fact that these recruits are negroes made any difference to the white soldiers in camp you are mistaken, for the white soldiers cheered and threw up their hats as truck after truck of negroes passed by, and the darkies shouted back lustily. […]

“I’se glad I got heah at last,” said a big negro as he lined up for classification. “I won’t have to pick no mo’ cotton, no sah; all I’se have to do is to parade in a nice new uniform an’ get three meals an’ a nice new gun….” (Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Sept. 25, 1918)

I’m sure the white soldiers were happy to see fellow recruits showing up, but the journalists — in story after story — treated the “negroes” (they were rarely called “men”) as bumbling caricatures, inevitably quoted in dialect. The United States armed forces were not integrated until 1948, and Black troops were segregated from white troops, both in camp and on the battlefield (when they were allowed to fight — they were largely kept in service positions such as stevedores).

On this Memorial Day, I share a report from Ralph W. Tyler, a Black journalist who had reported throughout the war from the front lines, on the casualties of African American soldiers who died during World War I in the service of the U.S. Army:

***

Sources & Notes

Top photo by John J. Johnson, from the National Archives is titled “Negro recuits [sic] having a turkey dinner just before leaving for a training camp. Dallas, Texas”; it can be accessed on the National Archives site here. An annotated version of this same photo appears under the title “Colored Troops — Negro recruits having a turkey dinner just before leaving for a training camp. Dallas, Texas” is here. (If anyone has additional info on the details of this photo, I’d love to know.)

“92nd Has Comparatively Small Casualty List” is an excerpt from Ralph W. Tyler’s article “General Order Commends Colored Officers” which appeared in The Dallas Express, Jan. 11, 1919. The full article can be read here.

For more info on the history of Black American soldiers, see the Wikipedia entry here; for info on the all-Black 92nd Infantry Division, see here.

Also, check out the blurb for the book Unjustly Dishonored: An African American Division in World War I by Robert H. Ferrell, here.

I’ve put a few articles on African American soldiers in WWI (including those cited above) in a PDF. A few of the articles appeared in the major Dallas and Fort Worth newspapers, and a couple appeared in The Dallas Express, the city’s newspaper published for a Black readership (including a rousing article by N. W. Harllee on the parade and celebration thrown by the city to honor the returning Black troops — WELL worth reading). Also included are a couple of unbelievable articles from the national press (including a lengthy one by a noted Stars and Bars reporter titled “Negro Soldiers Stationed at French Ports Sing and Dance While Unloading Ships”). The PDF can be accessed here (with articles in varying degrees of legibility).

The stirring and exhortative article “Dallas Gives Soldiers Befitting Celebration” by N. W. Harllee is in the PDF just mentioned, but it can also be found in a scan of The Dallas Express, here. UPDATE: Every scan of this article is hard to read, so I’ve tweaked the contrast to make it easier to read. You’ll have to magnify this sucker to read it, but it’s in a PDF here.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

1890

1890

ca. 1910-15

ca. 1910-15 Mrs. Morrill’s house at Ross & Harwood, 1894

Mrs. Morrill’s house at Ross & Harwood, 1894 The Morrill house — next stop: demolition, 1920

The Morrill house — next stop: demolition, 1920