Trinity Heights: The Tallent Furniture Studio and The Sunshine Home

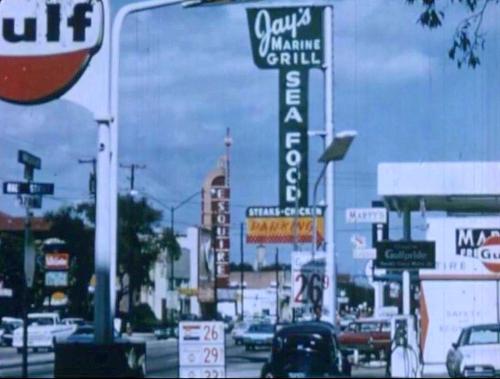

Vermont & South Ewing… (click for larger image)

Vermont & South Ewing… (click for larger image)

by Paula Bosse

The postcard image above shows a bird’s eye view of a few blocks in the Trinity Heights neighborhood of Oak Cliff, from the late 1940s. As I looked at it, I wondered a) what does this intersection look like now, b) what is that unlabeled building that looks like a jail behind the furniture store, and c) what was Tallent’s Furniture Studio?

Tallent’s Furniture Studio, owned by Raymond E. Tallent, was located at 815 Vermont Avenue.

1956

1956

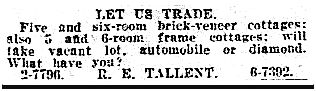

Not only did it house a furniture store, but it also served as an office for Tallent’s real estate business. According to Tallent’s obituary, he came to Dallas in 1920 and started his real estate business five years later. Starting out, he’d’ve been happy to trade you property for diamonds. “What have you?”

April, 1928

April, 1928

The first mention I found for the furniture store is this Christmas ad from 1947.

Dec., 1947

Dec., 1947

Tallent died in January of 1950 at the age of 53. Both of his businesses continued after his death, and the furniture store was still going in the late 1960s.

So, nothing out of the ordinary — just a small business, like thousands of other small Dallas businesses. Probably the most interesting thing about Tallent was that he had the good taste to have that great promotional postcard made. That strange little building behind the store was a lot more interesting.

*

What was that building? The first time it popped up on a Sanborn map was 1922: it was identified as a “County Detention Home” (click for larger image).

1922 Sanborn map detail — see full page here

1922 Sanborn map detail — see full page here

Despite its name, the “detention home” was not a correctional facility for juvenile delinquents, but it was a home for dependent children who had been made wards of Dallas County because of neglect or abandonment or because parents had died or were simply unable to care for them. This detention home was built in 1917 at 1545 South Ewing (“south of Oak Cliff”). During its construction in 1917, its roof collapsed, killing one of the workers.

Dallas Morning News, Apr. 13, 1917

Dallas Morning News, Apr. 13, 1917

The home was almost immediately overcrowded, and its superintendents were constantly scrambling for an increase in funding. Children, ranging in age from toddlers to teenagers, lived there as long as they needed — some for a few months, some for several years. They attended nearby schools, and even though they were wards of the court and were living in an institution, the people who ran the place tried to make it as home-like as possible. In January, 1934, the name of the county facility was changed to the much more cheerful “Sunshine Home.”

In 1950, the Sunshine Home received $165,000 in bond money for improvements and expansion, adding modern structures to the large campus but still retaining the original two-story red brick building built in 1917.

In 1975, the Dallas County Sunshine Home and the Girls’ Day Center merged, and the former Sunshine Home was renamed Cliff House.

In 2014, the 28,000-square-foot property on just under five acres was put up for sale, and in early 2015 plans for a charter elementary school were approved.

Below, a Google Earth image of the same view as the postcard featuring Tallent’s Furniture Studio, captured before the old Sunshine Home buildings had been demolished (click for larger image).

The view is remarkably similar to the one taken more than 65 years earlier. A little bleaker these days, perhaps, but certainly still recognizable.

***

Sources & Notes

Top postcard is from the Boston Public Library Tichnor Brothers Postcard Collection; it is viewable here.

Information on the plans for the KIPP Truth Academy submitted to the City of Dallas (with interesting illustrations/maps on pages 10 and 11) can be found in a PDF, here.

A recent Google Street View of this block of Vermont Avenue can be seen here. The Tallent furniture store occupied the building to the left of the Vermont Grocery.

The heart-tugging article “For All Loving Care Bestowed, Sunshine Home, Space Small, Needs Much to Cheer Children” (DMN, July 24, 1941) — written by popular Dallas Morning News columnist Paul Crume — describes daily life in the Sunshine Home and can be found in the Dallas Morning News archives.

A then-and-now comparison (click for larger image):

*

Copyright © 2015 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Feb. 15, 1914

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Feb. 15, 1914 DMN, Sept. 10, 1914

DMN, Sept. 10, 1914

DMN, Nov. 10, 1914

DMN, Nov. 10, 1914

DMN, Oct. 18, 1914

DMN, Oct. 18, 1914

“Dallas — The City That Decided Not To Die of Thirst”

“Dallas — The City That Decided Not To Die of Thirst”