Produce seller, Pearl Street Market

Produce seller, Pearl Street Market

by Paula Bosse

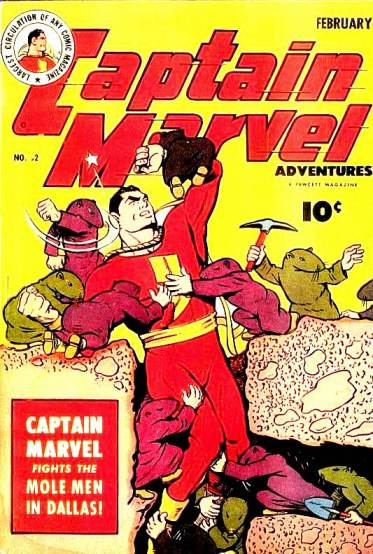

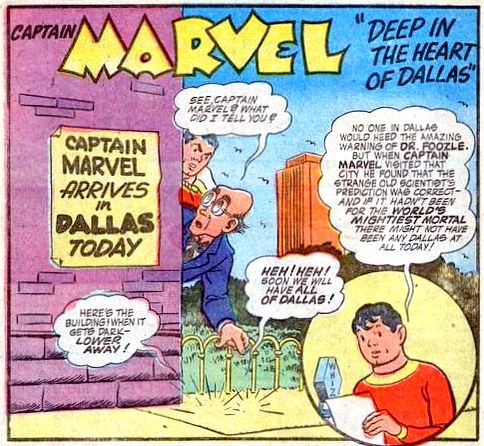

Last week I wrote about the produce market area in the neighborhood where the Farmers Market was eventually built, mainly because I had come across the above undated and unidentified photograph. I really wanted to know more about this photo, and the more I read about the area known in the ‘teens through the ’50s as the Pearl Street Market, the more I became fascinated by it.

I love this photo, but, sadly, I never found out who cafe-namesake Bob Taylor was, and I never discovered the identity of the man sitting on the sidewalk with his produce. BUT, I did realize that this produce seller was right across the street from one of the biggest wholesale produce sellers in Dallas, the Hines Produce Company. In fact, the photo below might show my mystery man’s view across the street. Both photos show the intersection of the 2000 block of Canton and the 400 block of South Pearl, the heart of the Pearl Street Market.

Hines Wholesale Produce Company, Canton & S. Pearl

Hines Wholesale Produce Company, Canton & S. Pearl

These two scenes look so wholesome — produce peddlers selling their fresh fruits and vegetables, quaint old cars and trucks parked along streets that are still vaguely familiar-looking, and the overall old-fashioned-ness of everything — all presented in nice, sharp, black-and-white photographs that always make me feel a little nostalgic, even though I wasn’t actually around back then and have nothing, really, to be nostalgic about.

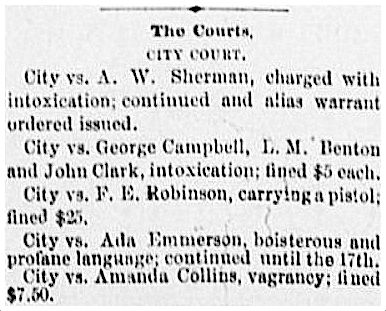

But “wholesome” is not a word that would have been associated with the Pearl Street Market. In fact, this was a part of town your mother would probably strongly suggest you not visit. Here are a few of the illicit activities that went on here on a fairly regular basis:

- Brawls in cafes, often involving weaponized broken beer bottles

- Shootings

- Stabbings

- Pickpocketing

- Burglary

- Robberies (of victims both asleep and awake)

- Gambling

- Muggings

- Drug dealing

- Arson

- Hit-and-runs

- Vehicular homicides

- Regular homicides

- Prostitution (I’m just guessing…)

- Shoplifting

- Vagrancy

- Selling another man’s melons and fleeing with the money

- The occasional being “severed” by a train

- Etc.

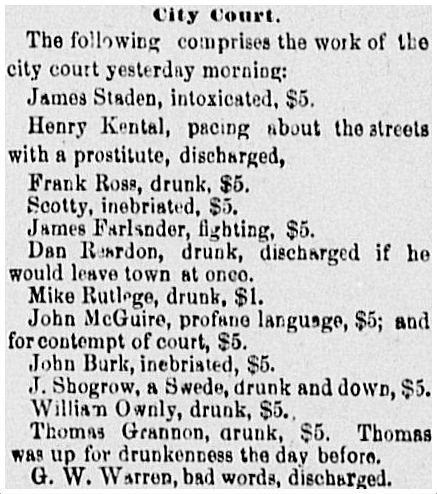

A typical police blotter story went something like this:

[Miss Esther Lee Bean] told physicians she was attacked by another woman who broke a beer bottle on her head and then used the jagged neck of the bottle as a weapon, cutting her several times on the right arm…. The affray occurred in a cafe in the 400 block of South Pearl. (Dallas Morning News, Dec. 17, 1938)

So … yes, very nostalgic.

Crime was a big problem, but what seems to have been even more upsetting to the people of Dallas was the general squalor of the place. Sanitary conditions were appalling. Rotting fruit and vegetables were thrown in the street, and live chickens were kept in cages, doing things that chickens do (which probably shouldn’t be done that close to things people might eat). And there were NO public toilets in the area — visiting farmers (who often bypassed the flea-bag hotels and slept in their trucks — or even on the sidewalks) routinely used the alleys as “comfort stations.” And then there were the rats. LOTS of rats. A staggering number of rats. Rats absolutely everywhere. Typhus? Not just a rumor. City sanitation crews would come by daily to hose the place down, but there was so much solid matter going down the drains that sewers were frequently clogged. It was, in a word, disgusting.

A typical hotel near Pearl & Canton, a bit cleaner by the ’50s

A typical hotel near Pearl & Canton, a bit cleaner by the ’50s

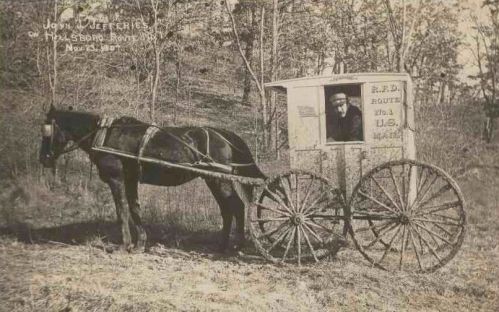

For years this part of Dallas, just south of the central business district, had been a place where farmers (and produce brokers) had been selling their fruits, vegetables, poultry, eggs, pecans, and whatever else they could haul into town. It was all very informal, and for much of that time it was completely unregulated. This part of town had been the base of the “truck farmers” since at least 1912. Before that, the market was at Pearl and Main, and in the earliest days it was at Ervay and Elm.

In 1914 a city-sanctioned (and presumably regulated) municipal retail market where vendors would sell directly to consumers was proposed, but eventually consumers became irritated that the produce they bought at the municipal market was significantly more expensive than that which could be purchased from the “hucksters” who parked along Pearl Street and roamed residential neighborhoods. The Pearl Street vendors sold primarily to wholesale customers, but over time, they opened up their stalls to the public and did a bustling business with housewives. The wholesale market was hit pretty hard by the 1930s as the number of independent grocers — once the major buyers on Pearl Street — diminished as chain stores took over. Those housewives became more and more important as time went on.

DMN, July 17, 1921 (click to enlarge)

DMN, July 17, 1921 (click to enlarge)

DMN, July 17, 1921

DMN, July 17, 1921

By the 1920s, the Pearl Street Market was well-established, and it was where one went to buy fresh (and “fresh”) fruits and vegetables. And according to this real estate ad, business was booming:

DMN, Nov. 4, 1923

DMN, Nov. 4, 1923

In 1933, The Dallas Morning News printed a fantastic, full-page, Runyonesque article about the “Pearl Streeters,” written by Eddie Anderson, who interviewed the colorful characters of the area and described the buzzing street life. With tongue only partially in cheek, he wrote: “Chicago has its Water Street. In New York you will find it on Washington. And if you go abroad there is the famous Smithfield Market of London and the vaulted bazars of Constantinople. In Dallas, it is Pearl Street.” Below, a photo that accompanied the story (click for larger image).

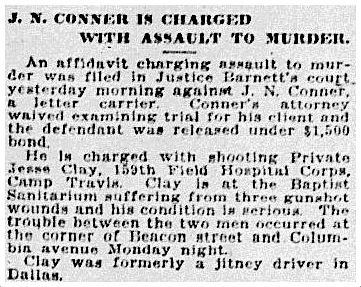

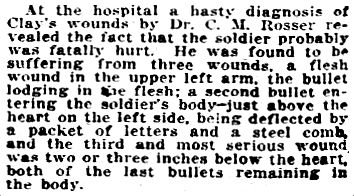

Anderson’s story was certainly entertaining, but it mostly glossed over the area’s more unsavory aspects. By 1938, there were louder and louder demands to clean up the neighborhood. Housewives organized and protested the deplorable conditions of the area, echoing points covered in a scathing Morning News editorial in which it was described as “a hazard to the health of the city because of the number of persons who visit it and because 75 per cent of the vegetables and poultry consumed in Dallas pass through that market” (DMN, Aug. 17, 1938).

In the early 1940s, the city finally stepped in and built the forerunner to the Farmers Market that we know today. By the 1950s, things in the squalor department had settled down a bit, and photos featuring pretty suburban housewives examining the produce and smiling children sampling fresh strawberries.

Nary a rat to be seen.

*

A street map of the Canton & Pearl area in about 1920, back when Canton Street was still part of an uninterrupted grid. (Note that many of the street names have changed over the years.)

***

Sources & Notes

Top photo (with Bob Taylor’s Cafe in the background) is from the author’s collection.

Photos of the Hines Produce Co. and the Prestwood (?) Hotel are from the Dallas Municipal Archives’ Dallas Farmers Market / Henry Forschmidt Collection, via the Portal to Texas History. You can browse this great collection here.

Map detail is from the very large “1919 Map and Guide of Dallas & Suburbs” (C. Weichsel Co.), via the Portal to Texas History, here.

The following DMN articles on the Pearl Street Market/Farmers Market are worth a read:

- “Pearl Street Market in Morning, Dallas’ Most Picturesque and Busiest Place in City” (July 19, 1925)

- “$1,500 Dope Cache Found Under Pile of Pineapples” (July 15, 1936), a story about a heroin bust with a headline that seems right out of The Weekly World News

- “Let’s Keep Our Pantry Clean,” editorial by Harry C. Withers (DMN, Aug. 17, 1938)

- “Dallas: The Old Public Market” by Tom Milligan (Aug. 15, 1966)

And even though I linked to it above, it’s so good and such a fun read that I’m going to mention it again: I highly recommend Eddie Anderson’s “Pearl Street Market As It Sees Itself” (May 14, 1933), here. Edward Anderson was an interesting guy: read about him at the Handbook of Texas here; read about his novels and see photos, here. All these years I’ve had his novel Thieves Like Us on my bookshelf, but I had never gotten around to reading it. Now I have a reason to!

I’ve gathered a pretty entertaining collection of crime reports from the Pearl & Canton neighborhood into one handy document, which can be read in all its seedy glory, here. SERIOUSLY. THIS IS FANTASTIC STUFF!

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

A saloon in a calm moment

A saloon in a calm moment (June 16, 1881)

(June 16, 1881) (June 3, 1881)

(June 3, 1881) (Oct. 27, 1882)

(Oct. 27, 1882) (Nov. 17, 1882)

(Nov. 17, 1882)

DMN, July 17, 1921

DMN, July 17, 1921 DMN, Nov. 4, 1923

DMN, Nov. 4, 1923

Fort Worth Register, Sept. 1, 1901

Fort Worth Register, Sept. 1, 1901 DMN, Jan. 2, 1918

DMN, Jan. 2, 1918 DMN, Jan. 1, 1918

DMN, Jan. 1, 1918

Greenwood Cemetery, Dallas (photo: David N. Lotz)

Greenwood Cemetery, Dallas (photo: David N. Lotz)