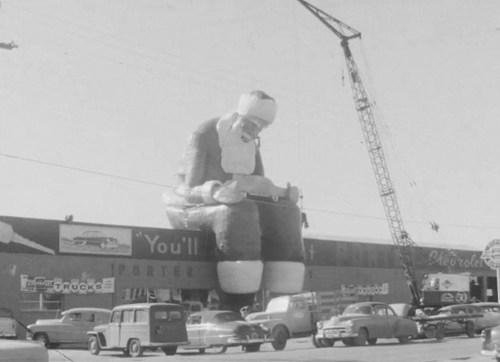

The World’s Largest Santa & The Christmas Tragedy — 1953

Santa considers a test-drive, 1953 (photo: Roy Addis)

Santa considers a test-drive, 1953 (photo: Roy Addis)

by Paula Bosse

Back in 2010, Robert Wilonsky (now a reporter for The Dallas Morning News, but back then a reporter for The Dallas Observer) posted a 1950s-era photo of a giant Santa Claus sitting on the roof of a Dallas car dealership. Robert had found the photo on eBay and wondered what the story behind the promotional stunt might have been. The thing that sparked my interest (other than it being a giant Santa Claus — holding a full-size car in his lap!) was the fact that the dealership, Porter Chevrolet (which I’d never heard of), had been just around the corner from where I grew up — it was in the 5500 block of E. Mockingbird, right across from the old Dr Pepper plant, about where the Campisi’s parking lot is now. I, too, really wanted to know more about that huge Santa Claus that had once been hanging out so ostentatiously in my neighborhood.

At about the time when Robert’s post appeared in 2010, I had only recently discovered that the Dallas Morning News archives were available online. For free. All the way back to 1885! (All you need is a current library card from the Dallas Public Library, and you’re on your way to losing absolute days while reading about one fascinating thing after another.) I had just begun to dabble with searches in the archives, so this seemed like a great opportunity to test my research skills and see if there was more to the story. And there was! I sent Robert what I’d found, and he wrote a great follow-up, here (which has yet another photo of the giant Santa). And a year later he did another follow-up, this one including the color photo seen above, sent in by a reader.

This is just such a great and weird holiday-related bit of Dallas’ past, that I thought I’d revisit the story, especially since some of the links in the original Observer posts no longer work.

First, a quick re-cap (but, please, read Robert’s story, because you’ll enjoy it, and it’s much more colorful than my quick overview here). During the 1953 Christmas season, Porter Chevrolet (5526 Mockingbird) commissioned Jack Bridges (the man who had previously made Big Tex (who was himself originally a giant Santa Claus)) to construct an 85-foot-tall steel-and-papier-mâché Santa Claus (he’d be that tall if he were standing) to sit on the dealership building and hold an actual 1954 Chevy in his lap. It was definitely a promotion that would grab people’s attention. The day the giant Santa was put in place, using a crane, a man whose company had done the installing (as they had with Big Tex), thought it would be a great opportunity to get a Christmas card photo of himself dangling from the crane next to Santa. The man, Roy V. Davis, was recovering from heart-related health problems, and, as it turned out, he experienced a “myocardial rupture” while hoisted 35 feet above the concrete parking lot. He lost his grip and fell to his death. This tragic news made the front page of local papers and was picked up by the Associated Press, but, oddly, it was never spoken of again. Giant Santa apparently remained at his perch throughout the holidays, but as far as I can tell, there was no further mention of Mr. Davis’ death — until Robert Wilonsky stumbled across the photo and wrote about it 57 years later.

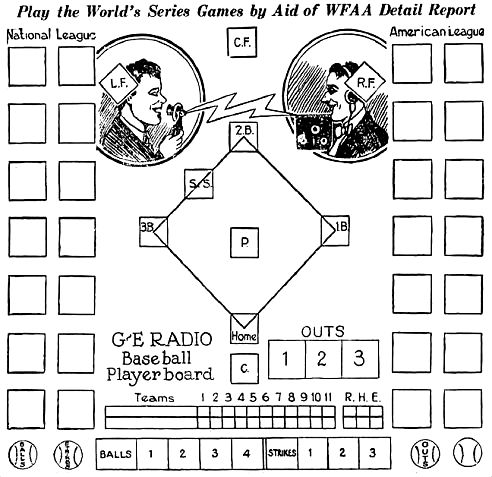

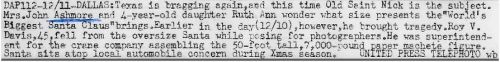

Below is the AP photo and blurb which ran nationally, showing Mrs. John Ashmore and her 4-year old daughter Ruth Ann looking up at the towering Santa Claus.

Photo: Collection of Paula Bosse

The caption (click for larger image):

**

UPDATE: Okay this is VERY EXCITING — and also kind of chilling: there is WBAP-Channel 5 television news footage of the Giant Santa as well as the on-the-scene tragic aftermath of Mr. Davis’ accident. The Dec. 10, 1953 footage is without sound (the script the anchor read on the air as the film played during the newscast can be found here). The video starts off with children marveling at the giant Santa Claus but suddenly turns dark with shots of the bloody Mr. Davis being loaded onto a stretcher (helped by Jack Bridges, the man who built the giant Santa, seen wearing a beret and white coveralls). The one-minute clip titled “Worker Dies at Santa’s Statue” can be viewed on the Portal to Texas History site here.

Below are a few screen captures:

**

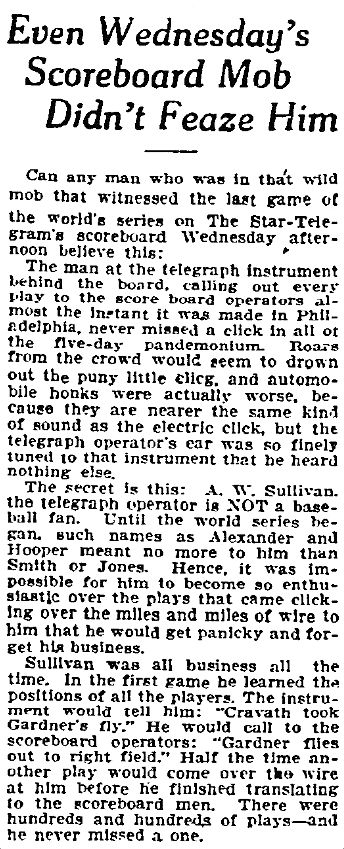

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Dec. 11, 1953

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Dec. 11, 1953

Lubbock Avalanche, Dec. 11, 1953

Lubbock Avalanche, Dec. 11, 1953

***

Sources & Notes

Top color photo (which I’ve cropped) is by Roy Addis. It appeared in the Dallas Observer blog Unfair Park in Robert Wilonsky’s 2011 update to the previous year’s story — it was sent in by a reader who discovered it in his personal collection. To read that story, click here.

Wilonsky’s original Unfair Park post — which contained the photo he found on eBay — is here. And, again, his post containing “the rest of the story” is here. (Robert Wilonsky continues to write enthusiastically about Dallas — its past as well as its present — and his Dallas Morning News pieces are, quite frankly, where I get most of my news about what’s going on in the city. Thanks for the opportunity to be part of the unearthing of this story, Robert!)

The news photo of Mrs. Ashmore and her daughter is from the author’s personal collection.

The video is from the KXAS-NBC 5 News Collection, University of North Texas Libraries Special Collections, accessible on the Portal to Texas History site. The main page of the video is here (click picture to watch video in a new window).

Dallas Morning News articles on the giant Santa and the tragic accident:

- “Santa Claus Turns Texan” (DMN, Sept. 23, 1953)

- “Figure of Santa Claus Will Overshadow Tex” by Frank X. Tolbert, with photo of Jack Bridges (DMN, Nov. 18, 1953)

- “Santa Claus Too Large For Trucks” (DMN, Nov. 29, 1953)

- “Christmas Card Picture With Tragic Ending” (DMN, Dec. 11, 1953)

- “Man Falls to Death Off Cable,” with photo of Roy V. Davis (DMN, Dec. 11, 1953)

UPDATE: Robert Wilonsky has written on the giant Santa in a new Dallas Morning News article, with some interesting new tidbits about Porter Chevrolet’s proposal to the City Council requesting permission to put this huge structure on top of the building. Read his 2017 update here. Robert keeps telling me we should write a book about this — or make a documentary. Which, of course, we should! After all these years now of visions of the giant Santa and sober thoughts of Roy Davis — more “real” now, having seen film footage of him bloody on that stretcher — I really do feel this is all part of some personal family Christmas lore, recounted every year around the table.

Pictures and clippings are larger when clicked.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

Neiman-Marcus ad — 1951

Neiman-Marcus ad — 1951 Neiman-Marcus ad — 1951

Neiman-Marcus ad — 1951 Volk ad — 1951

Volk ad — 1951 W. A. Green ad — 1951

W. A. Green ad — 1951

1939 Peruna (SMU Rotunda)

1939 Peruna (SMU Rotunda) 1960 Peruna (SMU Rotunda)

1960 Peruna (SMU Rotunda)

17-year-old David Wade, Waco High School, 1941

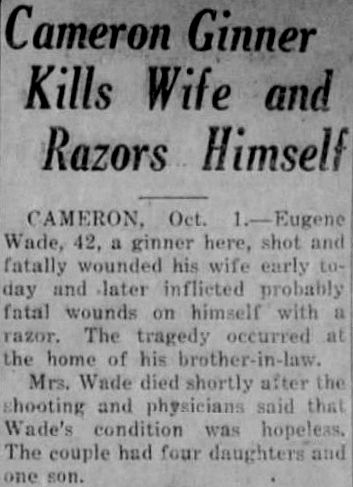

17-year-old David Wade, Waco High School, 1941 The Bryan Eagle, Oct. 1, 1929

The Bryan Eagle, Oct. 1, 1929

Bon Appétit!

Bon Appétit!

Flying the company colors

Flying the company colors July 1930, Dallas

July 1930, Dallas

Employers’ Casualty Co.’s casual employee — Oct. 21, 1932

Employers’ Casualty Co.’s casual employee — Oct. 21, 1932 1932

1932