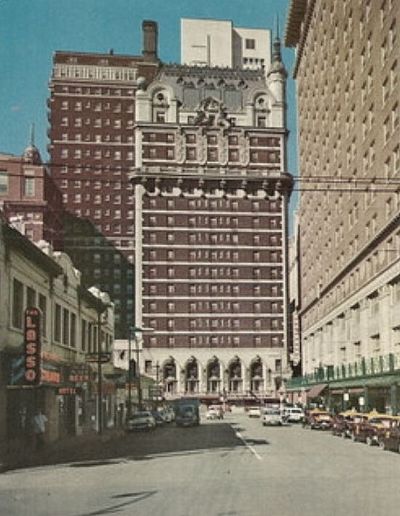

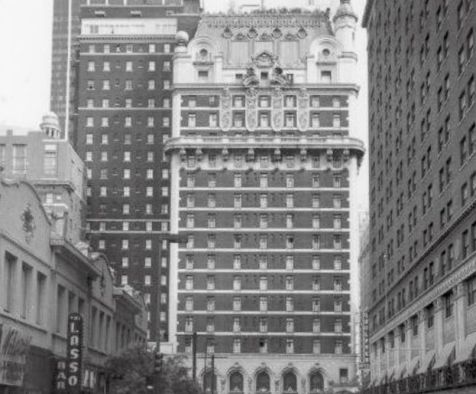

The Loveless filling station, Vickery, TX… (click for larger image)

The Loveless filling station, Vickery, TX… (click for larger image)

by Paula Bosse

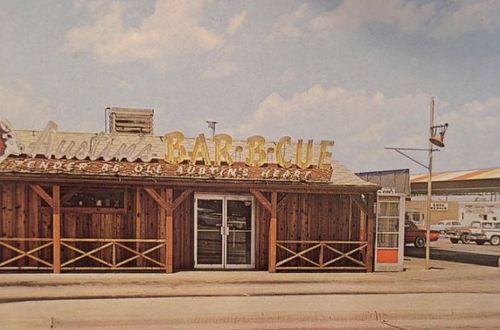

Perhaps you’ve driven past the site of the much-loved former burger place The Filling Station at Greenville Avenue and Park Lane recently and saw that the old building was undergoing renovation. Construction has ended, and a new Schlotzsky’s (the sandwich shop founded in Austin in 1971) has opened at 6862 Greenville Avenue. And it’s pretty cool that they’ve preserved this old 1930s building, a landmark to many Dallasites.

The original filling station and garage was built, according to family members, about 1931 — it was one of the first brick buildings in the small community of Vickery (which was annexed by Dallas in 1945). The construction even made the columns of the Richardson Echo (Dec. 11, 1931):

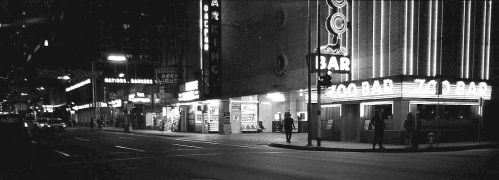

The business had begun in the early ’20s in another building across the street, but things were definitely looking up for the garage and its owners, William Homer Loveless and his son J. W. Loveless, when the new building went up. L & L Motors lasted 50 or so years until the early 1970s, when the once-sleepy Vickery area had exploded into part of “Upper Greenville,” an entertainment mecca lined with bars, restaurants, discos, and strip joints.

The Filling Station, a theme restaurant and bar decorated with gas station memorabilia, opened in 1975 and lasted a remarkable 29 years, closing in 2004. Filling Station super-fans still have fond memories of both the building and its menu of “theme” foods and drinks with names like “sedanwiches,” the Ethyl burger, the Tail Pipe, and the Ring Job.

Beyond being a nostalgic favorite from the go-go days of Upper Greenville, the real reason this place has always had historic appeal to Dallasites is because it is one of the still-standing Dallas-area locations with a tie to Bonnie and Clyde. According to Loveless family lore, the pair bought gas at the station at least once, sometime back in the ’30s. According to Sonya Muncy, whose father, J. W. Loveless, took over the station after her grandfather passed away:

“That was my daddy’s station and his dad’s before. When he got hurt in an auto accident and couldn’t work anymore, he sold it, and it became the first Filling Station restaurant. I think my mom still has pics of Daddy in front of it when he came out of the Army. Gas was 9 cents a gallon with 3 cents tax, for a total of 11 cents a gallon. He had the coldest Cokes around! Across the street where Park and Ride is was my grandmother’s house. I remember playing at the station as a kid and helping Daddy work on cars. When I got my first car, he made me change the oil and rotate the tires! Lol. It was called L & L Motors with Mobil gas. […] Bonnie & Clyde also got gas there and Daddy said they were always nice to him.”

Kevin Wood remembered when his grandparents happened to be at the station when Bonnie and Clyde stopped in:

“The day Bonnie and Clyde came in to fuel, Clyde shook my Pops’ hand.”

And in a later comment:

“My grandmother and grandfather were in the store the day B & C came in … always said they were very nice.”

*

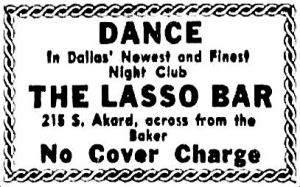

FUN FACT: Jack Ruby apparently ran a short-lived tavern called Hernando’s Hideaway right next door, at 6854 Greenville in the early or mid ’50s (he seems to have owned it and later sold it). It appears the building was torn down at some point. So … Bonnie and Clyde and Jack Ruby, together at last, cheek by jowl.

Greenville Ave., 1956 directory

*

For as long as I can remember, I’ve checked out this old building every time I drive by it, marveling that it has managed to remain standing all these years, and always afraid it won’t be there the next time I pass it. So thank you, Steve Cole, owner of this Schlotzsky’s, for bringing it back to life and appreciating it as much as a lot of the rest of us do.

**

The photos in this post were kindly sent to me by Jeb Loveless, grandson of Homer Loveless, the original owner. Below, perhaps the oldest photo of the building, in the Bonnie and Clyde era.

photo: collection of Jeb Loveless

photo: collection of Jeb Loveless

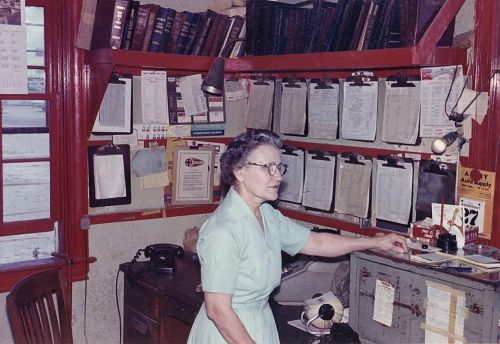

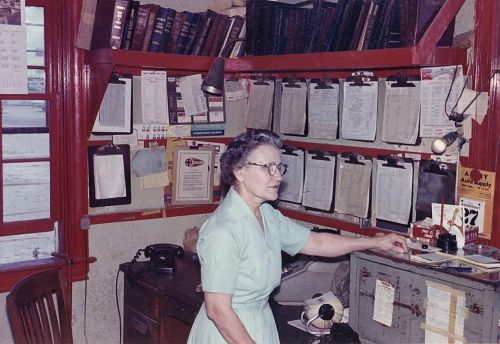

Below, Homer Loveless and his wife Jewel in 1956.

Jewel at work.

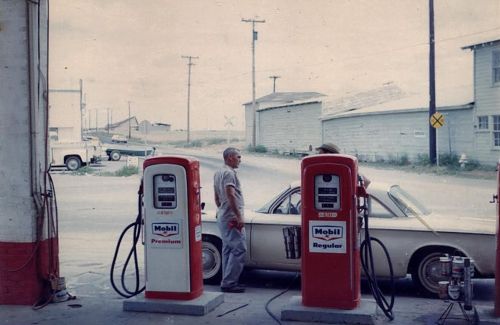

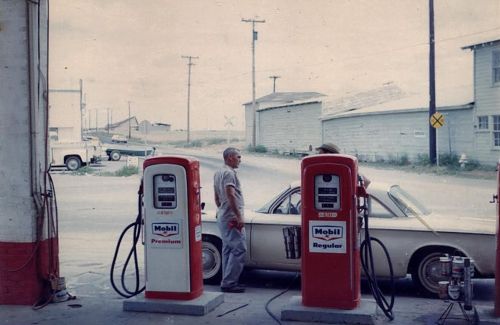

Homer and Jewel’s son (and co-owner) J. W., at the pumps.

UPDATE: I couldn’t for the life of me figure out what roads I was looking at here. Thanks to Danny Linn, I now know that the road straight ahead is what shows on 1962 maps as being the tail end/very beginning of Fair Oaks (this little bit still exists between Greenville and Central but is restricted to buses) — the view is looking west toward Central Expressway; the Corvair at the pumps is headed south on Greenville. A detail of this area from a 1962 map is below — note that Park Lane did not yet exist. (The full 1962 Enco map is here.)

(click me!)

(click me!)

J. W. with the tow truck.

And here is what the old Loveless garage looks like today, as a Schlotzsky’s, decorated with the original neon sign from its days as The Filling Station restaurant as well as with several of the photos reproduced in this post.

photo: Paula Bosse

photo: Paula Bosse

**

Aside from the Bonnie and Clyde connection, this little building (which has managed to stay standing for over 80 years — a feat in Dallas!) is known by most as the home of still-missed Filling Station restaurant.

Below, an interesting 1976 quote from Filling Station co-owner Bob Joplin about the “cutthroat” competition between ’70s-era Upper Greenville bars and restaurants (numbering at the time more than 50), wondering how long his place might stay alive:

“The average life of a new place on Greenville is probably about 18 months. If that. Hell, around the corner here — the Yellow Rose of Texas — how long was it open? Three months? Maybe less? […] We’re going great right now, but we’ve only been open a little more than a year. Check back with me later — we may be here, we may not.” (DMN, Nov. 14, 1976)

The surprising longevity of The Filling Station — 29 years in business! — is why the strangely unceremonious and surprisingly brief announcement of the Filling Station’s demise (which appeared in the pages of The Dallas Morning News on July 2, 2004) is so odd — its closure merited only ten words: “The Filling Station on Upper Greenville Avenue has also closed.” 29 years! That’s an eternity in the Dallas restaurant world.

eBay

A few other businesses occupied the building, but none managed to stay open very long. The building was vacant for several years, and it was definitely looking bedraggled when the Schlotzsky’s people came knocking.

Long-vacant — Google Street View, Aug. 2015

Long-vacant — Google Street View, Aug. 2015

And here it is, after renovation, preparing for its opening day as a Schlotzsky’s — the building now actually looks more like its original design, seen in the photo at the top of this post.

Schlotzsky’s Facebook page

Schlotzsky’s Facebook page

***

Sources & Notes

The photos of the L & L Motors garage and filling station in Vickery — and the Richardson Echo clipping — were sent to my by Jeb Loveless, grandson of Homer and Jewel Loveless and nephew of J. W. Loveless. He has graciously allowed me to use the photographs in this post. Thanks, Jeb! (Several of these photos were given to the owner of the new Schlotzsky’s and can be seen on the walls inside.)

Quotes from family members whose relatives met Bonnie and Clyde when they stopped in at the gas station are from comments on the Dallas History and Retro Dallas Facebook pages (used with permission).

A Lakewood Advocate interview with the owner of this Schlotzsky’s, Steve Cole, is here. He talks about his dedication to saving as much of the structure as possible, keeping the original brick walls and the wood floors.

To take a photographic tour through what remained of the old Filling Station, see the real estate listing on Zillow here (click on the first picture and a slideshow of large photos will open).

Here’s a then-and-now look at the building over the years:

Related articles in The Dallas Morning News:

- “William Loveless Dies After Illness” (DMN, June 12, 1960), obituary of the original owner, W. H. Loveless

- “A Filling Station Which Pumps Beer” by Patty Moore (DMN, Aug. 8, 1975), the first review of the new restaurant, The Filling Station

Click photos and clippings for larger images.

*

Copyright © 2016 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.