by Paula Bosse

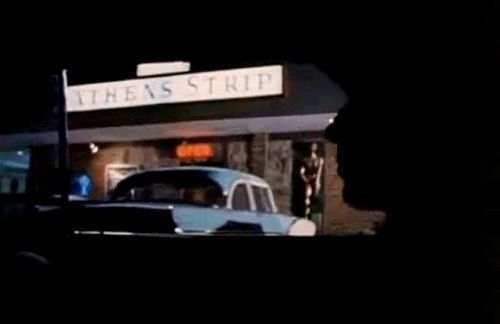

Growing up in Dallas with a father who was a classic country music fan, I’d always heard of The Longhorn Ballroom. And I’d always heard of Dewey Groom. You can’t have one without the other. The place is still around, but it keeps opening and closing and opening and closing. I don’t even know if it’s active at the moment, which is a real shame, because that place is COOL. I came too late to have seen the place at its glorious height as one of the country’s premiere country ballrooms. And I also came too late to witness the infamous Sex Pistols appearance there in the ’70s. I DID make it once or twice when it was going through its “alternative” period, booking bands that normally played in Deep Ellum. And I loved it. It was HUGE. Western kitsch everywhere. And a regular clientele comprised of people you’d either want to sit down and talk with for three hours or do your best to avoid completely — mostly the former. Below is a transcribed interview with Dewey Groom as it appeared (typos and all) in an old, obscure country music magazine that must have belonged to my father. At the end of this post are a few Dewey-factoids.

Even though his contributions are often overlooked, Dewey Groom was an important figure in the history of entertainment in Dallas. He died in 1997 at the age of 78. Thanks, Dewey!

*

***

*

*

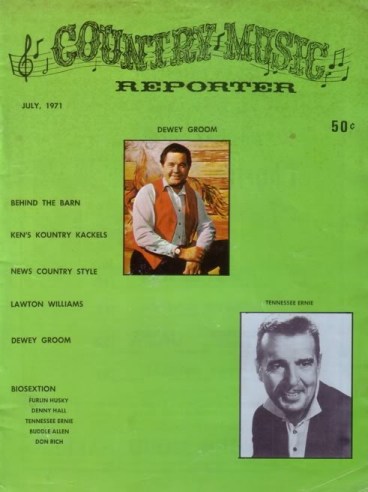

COUNTRY MUSIC REPORTER (Grand Prairie, Texas) – July 1971

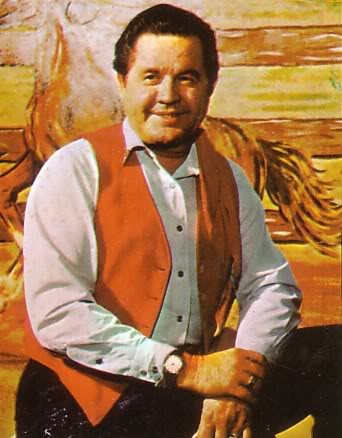

“Dewey Groom: From the Mabank Flash To Big Daddy of Country Music”

(writer uncredited — presumably Wayne Beckham, the magazine’s editor)

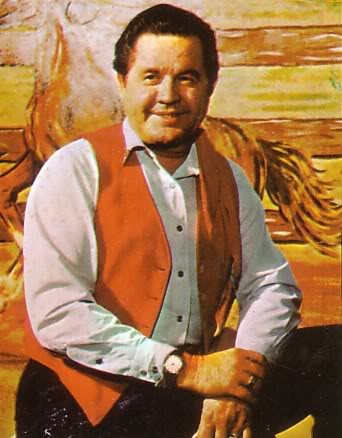

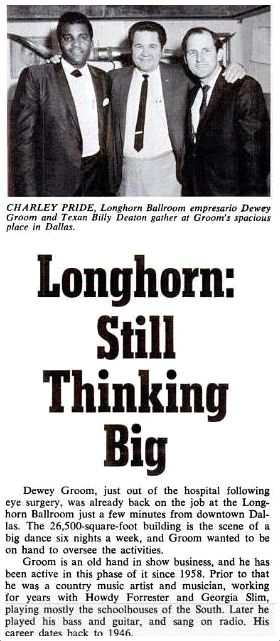

Back before he combined dancehall-keeping with his country singing, Dewey Groom was known on Dallas radio as the Mabank Flash – a reference to his Van Zandt County origins. He likes to talk of those origins, but he won’t complain nowadays if you call him the Lawrence Welk of country music.

I found him happy about his success as owner of the million-dollar Longhorn Ballroom on Corinth off Lamar [in Dallas, Texas]. But he was more inclined to talk of Angels Inc., the school for retarded children he helped found and hopes to see housed in a big new structure off Buckner, in East Dallas.

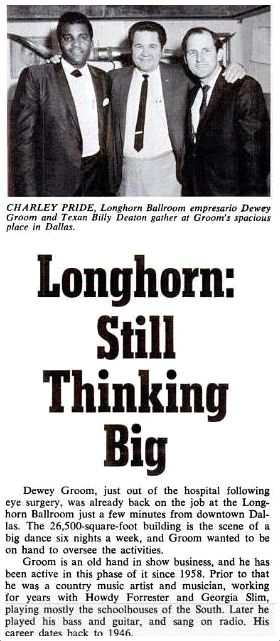

If he succeeds, it will be due to the middle-aged faithful who regularly go in thousands to the Longhorn to hear celebrities like Charley Pride or Jerry Lee Lewis, or simply to reassure themselves that the Mabank Flash of Dallas’ immediate postwar years is still in voice.

“I can’t yodel anymore,” Groom told me in the quiet-before-the-storm of a Friday afternoon, “but I still put in my 30 minutes singing and laughing up there with my band every working night – and I’m still hopeful that I don’t have an enemy in the world.”

Likely, he doesn’t; he’s climbed high in his 23 years of dancehall-keeping since he opened at 1925 1/2 Main in the old Bounty Ballroom. He’s on the phone steadily to Nashville picking the talent that makes the Longhorn one of the biggest sound chambers anywhere for the Nashville Sound.

Only big name he’s missed is Johnny Cash – and he, Groom avows, is the biggest: a real philosopher and humanist.

Back in Groom’s youth the big name, he says, was Jimmie Rodgers, the old blues singer who started country music. But even before Rodgers became famous in the ’20s, the Groom family was a gospel singing crowd for certain.

“Daddy sang and my uncle was a singing schoolteacher,” he says. “In Deep East Texas, singing schools were everywhere. I joined. They taught you to read music and keep time. Gospel singing is pretty close to country music; so evenings we’d go across the fields to Uncle Bert Wise’s and listen to Jimmie Rodgers. Uncle Bert had the only phonograph around and got all the new records.”

Dewey imitated what he heard, but his friends said everything came out like Gene Autry. He believed them and went to look for a wider audience. He landed in Dallas at 10 with his guitar, but instead of instant fame, found work in a garage.

“I’d get up in the night and hang around a midnight radio show – I’d drop in on Bill Boyd’s old live 6 a.m. program on WRR,” he recalls. “Sometimes he’d let me sing on that show – the big time.”

But it wasn’t until he donned a uniform in 1941 that Groom had a real chance to stretch his lungs. He started singing in army rec halls and when he got overseas became the “Western part” of a divisional GI band which entertained for 42 months in the New Guinea area and Australia.

“I guess I became a professional then,” he reminisces, “but it was Hal ‘Pappy’ Horton that got me going in civilian life. I won $50 first prize on Pappy’s old Hillbilly Hit Parade in 1946. Then when he started his noon-time Cornbread Matinee, I was the singer. The show was a tremendous hit for 200 miles around Dallas. Pappy brought in Gene Autry and Roy Acuff. I was a hit, too. I played school shows and they used to tear the buttons off my clothes. Nobody knew it, but the Mabank Flash’s wife was making those pretty clothes I wore. I was the biggest thing in country singing around here, but she was the biggest thing in keeping me going.”

But Pappy died and the school shows Groom loved petered out. Too many bands were vying for a chance to put on shows in the schools. So Groom went to playing dances.

He ended up with Jack Ruby at the Silver Spur.

“I made Jack a lot of money,” he recalls, “at the time when he was deep in debt.”

“What kind of man was he?” I asked.

“A driver, and a talker – very emotional. Everybody liked him. He’d do anything in the world for you. But he didn’t understand country music. He wanted a sophisticated place, which you can’t have. He ran away my followers as fast as they turned up. Finally, the police that hung around the place told me I ought to get into business for myself. I borrowed $500 and opened up.”

It’s been a rough haul, says Groom, and he’s made it through several locations only because he understands the business – and that takes years.

Too many men rise and fall. Bob Wills, for instance, was the biggest bandleader in the world at one time – he outdrew Tommy Dorsey. Now – well, Groom will have a “tribute” dance for Wills, a man whom, next to Pappy Horton (whom he reveres as a great and good man), Groom admires most.

He cut his professional teeth on Wills’ songs – especially San Antonio Rose which, he confides, is simply an earlier Wills hit, Spanish Two Step, played backwards. Groom also has a taped narrative of Wills’ life, which has been a big radio hit. He expects the Wills Tribute Night to be a success.

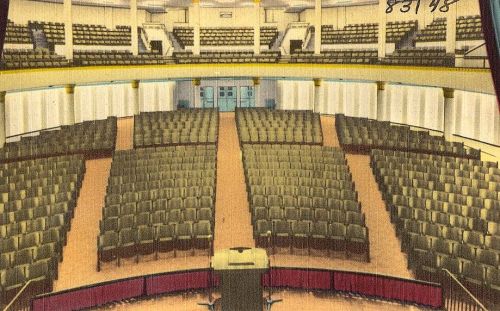

“You can squeeze 2,000 people into the Longhorn,” he says, “and I guarantee the top guest stars from $1,500 to more than $2,000. They always make more than the guarantee. This week, it’s Ray Price. Other big names are Charley Pride, the Negro country singer, who I rank next to Johnny Cash, and people like George Jones, Tammy Wynette, Harold Morrison and Conway Twitty.”

As a lifetime member of the Country Music Hall of Fame, Groom is certain that another gospel-singer-type – Jimmy Davis, former governor of Louisiana – will go in the Hall of Fame this year.

Groom is sentimental about the old times and old-timers, but he knows it’s harder to please people nowadays. Variety is demanded. Even a little pop gets mixed with country music.

“People think I’m rich and I guess sometimes I want them to think so,” he confides, “but I don’t want to be. I want friends and I want to finish that school for Angel Inc. If I can do these two things, I’ll be happier even than I was when I was the Mabank Flash.”

“Daddy Dewey,” as he is known by many artists and fans, knows practically all the stars. He has had many of them on his stage. Dewey has contributed much to many artists in helping to get them started. Through the years he has recorded many records and written many songs as well.

The Longhorn Ballroom came about in October, 1968. Since then he has also purchased the old Guthrie Club and torn out the wall to increase the seating capacity to over 2,000, on a 4 1/2 acre plot that cost nearly $500,000.

Dewey Groom has become an authority on country music. He is often called upon for informative opinions on new country clubs or organizations. Many fellow club owners are personal friends and often obtain information about artists and business – [there’s no] bitterness that often comes in competition.

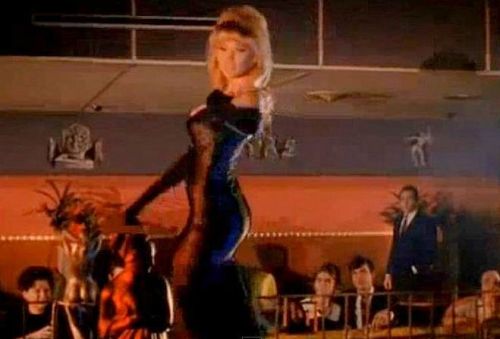

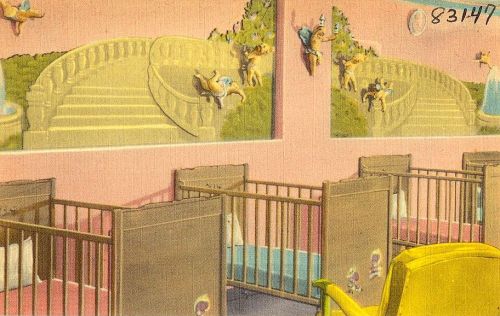

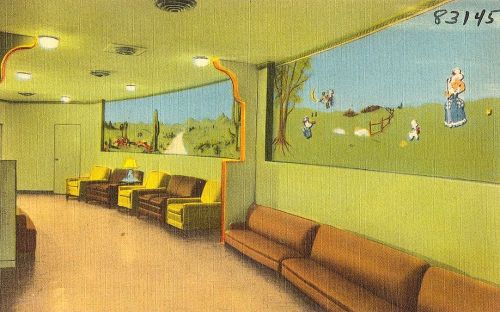

It’s been a long way since Dewey first traded a bull-calf for a guitar to the present-day Longhorn Ballroom. It is without doubt “America’s Most Unique Ballroom.” A landmark in Dallas, and one of the few western ballrooms in America. Hand-painted murals cover the walls and country decor prevails. Top country artists appear here weekly [and] Dewey’s own 12-piece band appear[s] nightly.

**

Below, photos from the article showing a partial view of the sprawling interior, complete with fantastic cactus pillars, as well as a couple of exterior shots showing Western street-scenes outside the club in a horseshoe around the parking lot. (Click to see larger images.)

***

Sources & Notes

Incidentally, I have moved this post from another blog I had a long time ago. Without question, this got more hits and more comments (…more than 50!) than anything else I’d ever posted. People loved the Longhorn Ballroom, and a lot of them miss the days of dancing and drinking at the legendary dancehall (which just happened to be in a very seedy part of town, at Corinth and Industrial). Long live the Longhorn! (Also, I think it’s high time we bring “Dewey” back into the baby-name-pool. Along with “Roscoe.” … And maybe “Lon.” Pass it on.)

A short interview with Dewey on his retirement — “Adios, Longhorn Ballroom” by Mike Shropshire — was printed in Texas Monthly (March 1986) and can be found here.

Dewey Groom’s record label, Longhorn Records, was fairy active. He even put out some recordings of himself. I just listened to “Butane Blues” and I realized it was the first time I’d ever heard his voice (Dave Dudley meets Malcolm Yelvington). Listen to his recording on YouTube here.

Check out a cool photo of Dewey and his band in the early ’50s here.

A weird little detour into Dewey’s 8-page Jack Ruby-related file in the Kennedy assassination investigation (in which “barber” is listed as his profession) can be found here.

Below a short piece from Billboard (Nov. 21, 1970).

And, finally, a nice history of the Longhorn Ballroom by Jeff Liles (who booked bands there for a while in the post-Dewey era) can be read on the Dallas Observer website here.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

Greenwood Cemetery, Dallas (photo: David N. Lotz)

Greenwood Cemetery, Dallas (photo: David N. Lotz)

Date unknown

Date unknown

DMN, Jan. 1, 1909

DMN, Jan. 1, 1909

DMN, Aug. 11, 1914

DMN, Aug. 11, 1914