An Oriental Oil Co. competitor, at 1805 Commerce

An Oriental Oil Co. competitor, at 1805 Commerce

by Paula Bosse

I cropped this detail from a much larger view of Commerce Street because this incidental, everyday moment caught my attention. Was that man filling his automobile with gasoline? Was that square, boxy, hip-high thing full of gas, right there at the curb of one of the city’s busiest streets? The sign above the pump reads “PENNSYLVANIA AUTO OIL GASOLINE SUPPLY STATION.” I looked into it, and now I know more about early gas pumps and stations than I ever thought I would.

In the very early days of automobiles, one would have to seek out a supplier of gasoline (such as a hardware store or even a drugstore) where you would buy a gallon or two and carry it home with you in a bucket or something and then carefully pour it into your car’s gas tank using a trusty funnel. After a few years of this inconvenient way to gas up, these curbside pumps began to pop up in larger cities. The pump seen above was at 1805 Commerce St. and belonged to the Pennsylvania Oil Company. It opened in early 1912. That got me to wondering about other such fueling stations, and it seems the first in Dallas may have belonged to the Oriental Oil Company, just down the street from the one seen above, at 1611 Commerce. Here is a fuzzy image of it, from the same, larger photo the detail above was taken from. (Click for larger image.)

Could this photo have been taken there? It was listed on eBay merely as “Oriental Oil Company, Dallas, 1910-1920.”

Oriental Oil’s first “auto station” opened in February, 1911, where “facilities have been arranged so as to fill the cars along the sidewalk.”

(Dallas Morning News, Feb. 26, 1911)

(Dallas Morning News, Feb. 26, 1911)

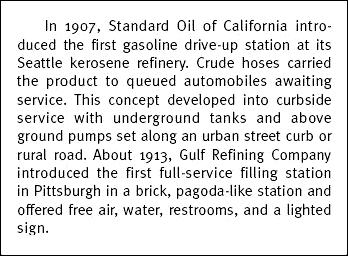

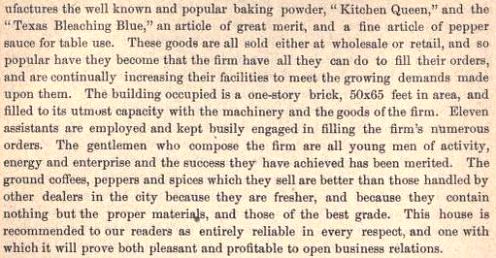

Drive-up “stations” had begun to appear a few years before, on the West Coast.

(Texas Dept. of Transportation, 2003)

(Texas Dept. of Transportation, 2003)

In a 1924 Dallas Morning News article (see below), the pump seen in the above photos was described thusly:

Dallas’ first gas filling station had a one-gallon blind pump on the curb which was then thought to be the last word in equipment. Now if a filling station is not equipped with a visible five-gallon pump it is thought to be behind the times and the gas now sold must be water white, when in the old days it was most any color.

This, I think, is what the Oriental and Pennsylvania rolling tanks looked like — the make and model may be different, but I think the general design is the same:

When it was empty, it would be rolled away to be re-filled. I’m not sure about the payment system. Coupon books are mentioned in one of the ads, but I don’t know how (or with whom) one would redeem them as these pumps appear to be self-serve. Perhaps there was a slot for coins/coupons, and everyone worked on the honor system.

It seems that its placement would cause a lot of congestion on a major street like Commerce (which at the time was still shared with skittish horses), but Commerce was also a hotbed of automobile dealerships (Studebaker, Stutz, and Pierce-Arrow dealerships, for example, were within a couple of blocks of the Oriental and Pennsylvania filling stations).

The Oriental Oil Company — a forgotten, early oil company — had an interesting history. The Dallas-based company began business in 1903, starting their company “in a barn in the rear of the Loudermilk undertaking establishment.”

(Southern-Mercury, Dec. 31, 1903)

(Southern-Mercury, Dec. 31, 1903)

They were a fast-growing oil company (“an independent concern which in spite of the strong opposition of the oil trust is now enjoying permanent and growing prosperity” – Greater Dallas Illustrated, 1908), and they were one of the first to open a refinery in Texas (they eventually had two refineries in West Dallas). The company’s primary concern in its early years was the manufacture of various oils and greases for industrial use.

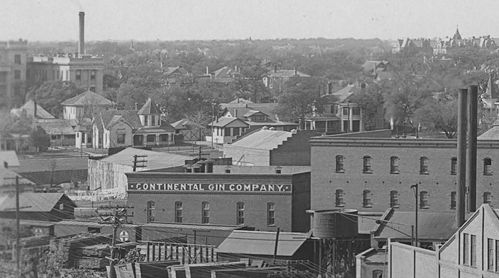

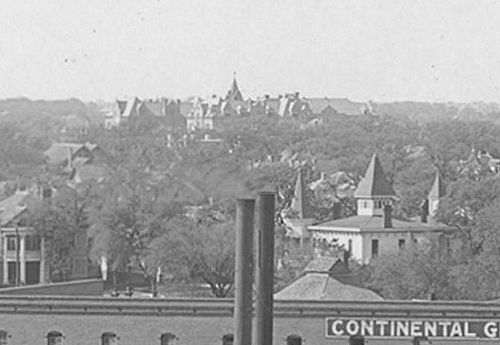

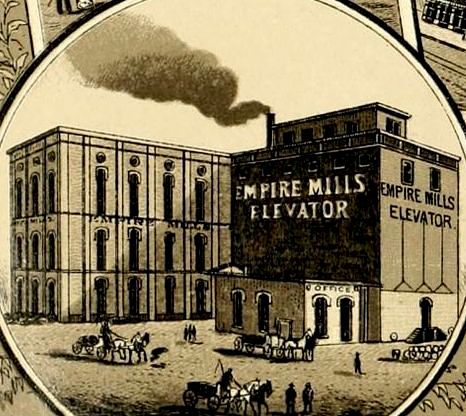

Oriental Oil Company Factory, corner of Corinth St. and Santa Fe tracks, circa 1908

Oriental Oil Company Factory, corner of Corinth St. and Santa Fe tracks, circa 1908

In 1911, understanding just how profitable the new world of retail gasoline sales could be, they installed their first pump at the curb of 1611 Commerce St., near Ervay (“right behind the Owl Drug Store”). A 1924 Dallas Morning News account of the company (see below) states that this was the first gas pump … not only in Dallas … but in the entire state of Texas. I’m not sure if that’s true, but the Smith Brothers who ran Oriental Oil were certainly go-getters — the Smiths were grandsons of Col. B. F. Terry, organizer of the famed Terry’s Texas Rangers, and one of the brothers, Frank, was an early mayor of Highland Park and a three-term president of the Dallas Chamber of Commerce.

(DMN, Oct. 8, 1911)

(DMN, Oct. 8, 1911)

(DMN, Jan. 28, 1912)

(DMN, Jan. 28, 1912)

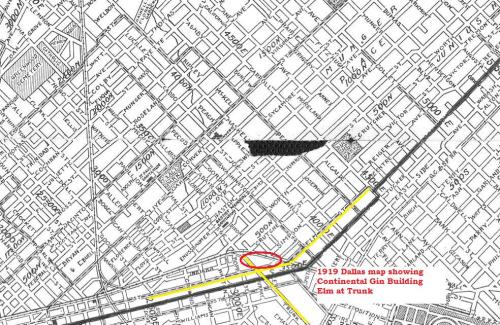

Shortly after opening their first pump on Commerce, demand was such that a second pump was soon opened at 211 Lane St. (a mere half a block away!). The DMN reported on Oct. 19, 1911 that a competitor — Consumers’ Oil and Auto Company — was going to be right across the street: “Permission was given to the Consumers’ Oil and Auto Company to place a gasoline tank under the sidewalk at 214 Lane street.” And in March 1912 the Pennsylvania Oil Company was installing ITS underground tank for the pump seen in the photo at the top — again, less than a block away. And in 1916 Oriental opened its splashy new “‘Hurry Back’ Auto Station” right across the street from where that Pennsylvania tank had been. (That Commerce-Ervay area was certainly an early gas station hotbed!)

(DMN, Aug. 29, 1916)

(DMN, Aug. 29, 1916)

Newspaper reports also cite claims made by the company that the station mentioned in the ad above — at Commerce and Prather — was the first drive-in gas station in the United States. I’m sure this was good truth-stretching PR for Oriental more than anything, because this claim was not true (Seattle and Pittsburgh seem to be battling each other for that honor). It might not have been the first, but when this “auto station” opened in 1916 (assuming it was “new” as this ad states), it was still pretty early in the history of the drive-in filling station. Also, by 1916, “Hurry Back” had become the company’s slogan as well as the name of its gasoline.

(DMN, Oct. 22, 1918)

(DMN, Oct. 22, 1918)

(Jewish Monitor, 1920; detail)

(Jewish Monitor, 1920; detail)

(DMN, Apr. 11, 1921)

(DMN, Apr. 11, 1921)

(DMN, Mar. 5, 1922)

(DMN, Mar. 5, 1922)

I love these ads!

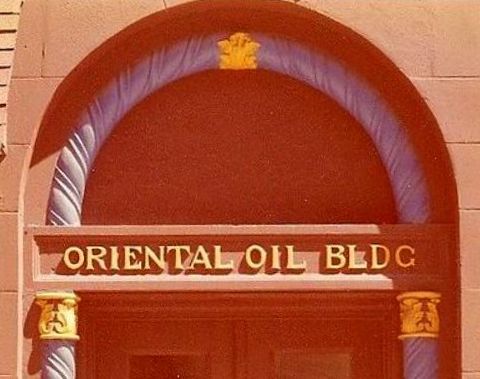

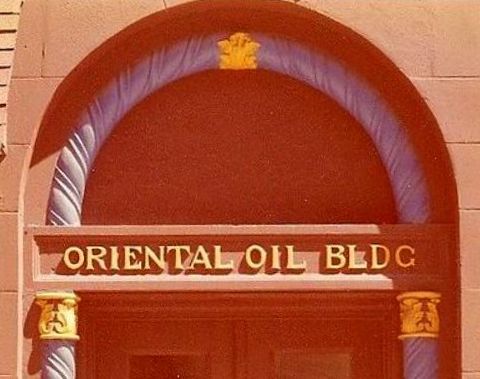

By 1927, the company boasted at least 18 filling stations, two refineries, and branches in Fort Worth and San Antonio. In 1927 they had moved into new offices in the “Oriental Building” at the nexus of Live Oak, St. Paul, and Pacific. A newspaper report described the building as being “finished in Oriental colors with Oriental decorations and is marked at night by very attractive lighting” (DMN, May 1, 1927).

The Oriental Oil Company declared bankruptcy in 1934, selling off their property, refineries, and their name. No more Oroco gas. A lot of companies went bust during the Great Depression, but I’m not sure what precipitated Oriental Oil’s bankruptcy. Actually, I’m surprised by how little information about the Oriental Oil Company I’ve been able to find. Afterall, it and its “Hurry Back” gasoline played a major role in getting the residents of Dallas off their horses and behind the wheel, a major cultural and economic shift that changed the city forever. And it all started at that weird little curbside gas pump on Commerce Street.

***

Sources & Notes

The first two images are details of a photograph by Jno. J. Johnson (“New Skyline from YMCA”), 1912/1913, from the DeGolyer Library, Central University Libraries, Southern Methodist University, viewable here.

Snippet of text from A Field Guide to Gas Stations of Texas by Dwayne Jones (Texas Department of Transportation, 2003).

Illustration of the two 1913 Tokheim portable gas pumps from An Illustrated Guide to Gas Pumps, Identification and Price Guide, 2nd Edition by John H. Sim (Iola, WI: Krause Publications, 2008).

Drawing of the Oriental Oil Company Factory from Greater Dallas Illustrated (Dallas: American Illustrating Co., 1908 — reprinted by Friends of the Dallas Public Library in 1992).

All ads and articles, unless otherwise noted, from The Dallas Morning News.

Color photo of the pink, purple, and gold Oriental Oil Bldg. is a detail from a photo taken around 1977, on Flickr, here.

For an interesting (and mostly accurate) mini-history of the Oriental Oil Company, then in its 20th year of operation, see the Dallas Morning News article “First Dallas Filling Station on Commerce Had One-Gallon Pump” (June 22, 1924).

Some nifty info on early gas stations (yes, really) here.

More info with some really great illustrations and photos here.

Another surprisingly fun and informative article is here.

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

Soda fountains came from here…

Soda fountains came from here…

(click for larger image of house)

(click for larger image of house)

Google Street View

Google Street View

Oct. 1954 (©Bettmann/CORBIS)

Oct. 1954 (©Bettmann/CORBIS)

Today, via Google Street View

Today, via Google Street View

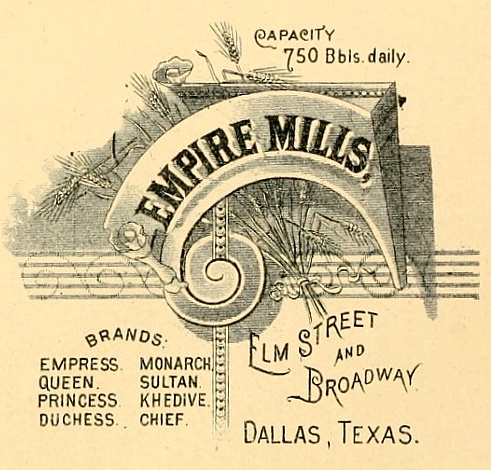

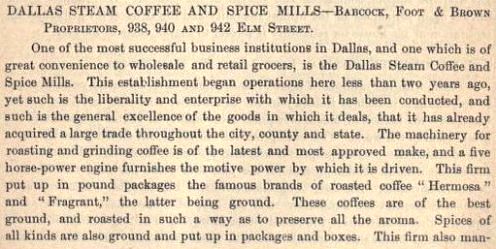

Flour central!

Flour central! DMN, May 30, 1886

DMN, May 30, 1886 DMN, July 5, 1886

DMN, July 5, 1886

(Texas Dept. of Transportation, 2003)

(Texas Dept. of Transportation, 2003)

(Southern-Mercury, Dec. 31, 1903)

(Southern-Mercury, Dec. 31, 1903)

Excerpt from “Hold the Roses” by Rose Marie

Excerpt from “Hold the Roses” by Rose Marie June 1945

June 1945