When the Spanish Influenza Hit Dallas — 1918

American Red Cross at Love Field, spraying soldiers’ throats, Nov. 6, 1918

by Paula Bosse

The Spanish Influenza pandemic of 1918-1919 caused as many as 50 million deaths worldwide — about 600,000 of which were in the United States (11 times greater than the number of American casualties during World War I). Locally, the influenza first hit the soldiers at Camp Bowie in Fort Worth in September, 1918. The flu spread quickly, and on Sept. 27, it was reported that there were 81 cases in the camp. Well aware of the devastation the flu had wrought in other U.S. cities, most notably at military camps, Fort Worth was, understandably, taking the situation seriously. Dallas leaders, on the other hand, were all-but pooh-poohing the need for concern. On Sept. 29, The Dallas Morning News had a report titled “Influenza Scare is Rapidly Subsiding” — the upshot was that, yeah, 44 reported cases of “bad colds” had been reported in the city, but there’s nothing to worry about, people.

In the opinion of the military and civil doctors, the Spanish Influenza scare is unwarranted by local conditions. The few cases of grip, it is claimed, are to be expected as the result of the recent rainy weather.

Just two days later, though, officials were jolted out of their complacency when the (reported) cases jumped to 74 (click for larger image):

DMN, Oct. 2, 1918 (click for larger image)

DMN, Oct. 2, 1918 (click for larger image)

The months of October and November were just a blur: the city was plunged into an official epidemic. There was no known cure for the flu, so a somewhat ill-prepared health department preached prevention. People were encouraged to make sure their mouths were covered when they coughed or sneezed, and they were directed to not spit in the street, on streetcars (!), in movie theaters (!!), or, well, anywhere. (Handkerchief sales must have soared and spittoon sales must have plummeted.)

At one point or another, places where people gathered in large numbers — such as schools, churches, and theaters — were closed. Trains and streetcars were required to have a seat for every passenger (no standing, no crowding) (…no spitting). The number of mourners at funerals (of which there were many) was limited. And there was a major push for citizens to clean, clean, clean their surroundings in an attempt to make the city as sanitary as possible. Instructions appeared often in the newspapers.

It was estimated that there were 9,000 cases of Spanish Influenza in Dallas in the first six weeks. By the middle of December, when the worst of the outbreak was over, it was reported that there had been over 400 deaths attributed to the Spanish Influenza and pneumonia in just two and a half months.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Dec. 11, 1918

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Dec. 11, 1918

As high as these numbers were, Dallas fared much, much better than many other parts of the United States.

***

Sources & Notes

Photo at top was taken on November 6, 1918 and shows American Red Cross Workers spraying throats of military personnel based at Love Field in hopes of preventing the spread of the influenza. The photo is from the Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine; I found it on the NMHM site, here. (Click photo for larger image.)

Ad for Pepto-Mangan (“The Red Blood Builder”) was one of a flood of medicines and tonics claiming to be effective in the fight against Spanish Influenza (none were).

For a detailed and remarkably well-researched, comprehensive history of the Spanish Influenza in Dallas, see the article prepared by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine, here. It’s pretty amazing.

To read about the history of pandemics (including several good links regarding the Spanish flu), see the Flu.Gov site, here.

And, NO, Ebola is not transmitted like the flu. But it’s still good practice to cover your mouth when you cough or sneeze,wash your hands frequently, and never EVER spit in the street, because that’s just disgusting. ((This post was originally written in 2014 while Dallas was the center of the Ebola universe.))

More on the Spanish Influenza pandemic can be found in the Flashback Dallas post “Influenza Pandemic Arrives in Dallas — 1918.”

*

Copyright © 2014 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

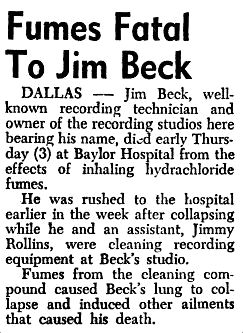

Jim Beck in his studio

Jim Beck in his studio Jim Beck (right) with Hank Thompson

Jim Beck (right) with Hank Thompson Billboard, May 12, 1956

Billboard, May 12, 1956

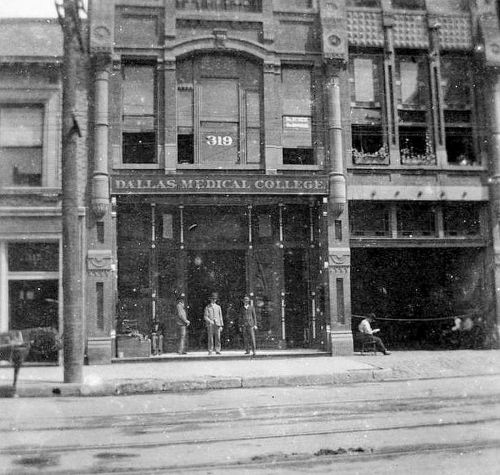

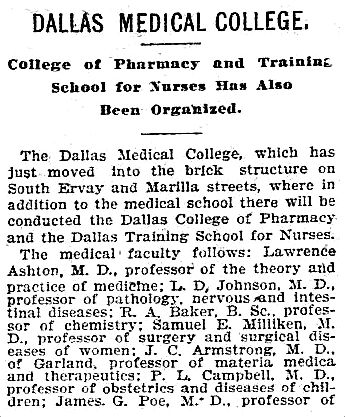

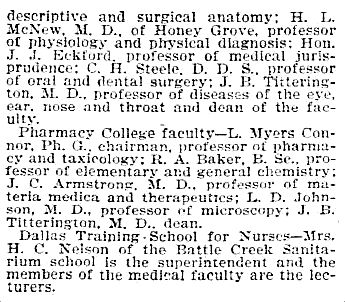

Dallas Morning News, Feb. 3, 1901

Dallas Morning News, Feb. 3, 1901

Southern Mercury, Nov. 10, 1904

Southern Mercury, Nov. 10, 1904

DMN, Jan. 1, 1909

DMN, Jan. 1, 1909

DMN, Aug. 11, 1914

DMN, Aug. 11, 1914

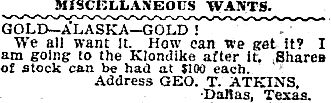

Southern Mercury, Oct. 9, 1888 (detail)

Southern Mercury, Oct. 9, 1888 (detail)

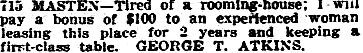

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 12, 1888

Dallas Morning News, Dec. 12, 1888 DMN, June 3, 1888

DMN, June 3, 1888  DMN, Aug. 8, 1897

DMN, Aug. 8, 1897 DMN, Oct. 20, 1918

DMN, Oct. 20, 1918 DMN, Aug. 9, 1920

DMN, Aug. 9, 1920