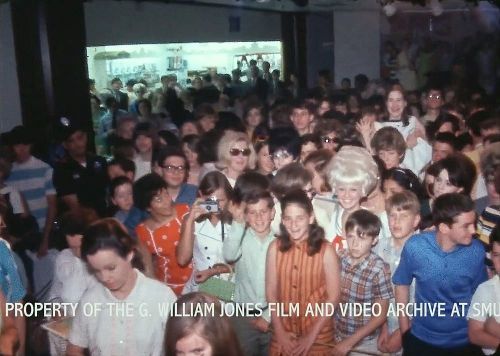

Tiny Tim Mobbed at the Melody Shop — 1969

Dallas teens loved Tiny Tim… (Sanger-Harris book-signing, June 1969)

by Paula Bosse

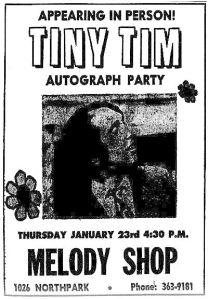

Tiny Tim — one of the most … unusual performers of the 1960s — was a hit with teenagers when he made his first appearance in Dallas at the Melody Shop in NorthPark mall on January 23, 1969. What had been expected to be a nice little autograph party which might attract a small number of fans and curiosity-seekers turned into something altogether unexpected.

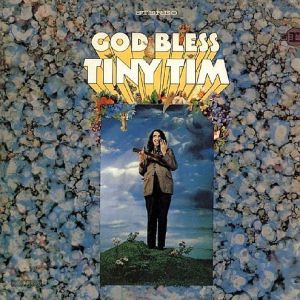

Tiny Tim (…”Tiny”? “Tim”? “Mr. Tim?”…) had the unlikeliest of hits during the hippie-era: “Tiptoe Through the Tulips,” a lilting little ukulele-accompanied song which had originally been a hit in 1929. Tiny Tim’s first few appearances on U.S. television must have caused a lot of heads to be scratched and/or jaws to be dropped. He was just kind of … weird. But gentle, and he seemed to be a genuinely nice fellow who just happened to have a penchant for songs from the megaphone-era of popular music. If you’ve never seen footage of a Tiny Tim performance, search for a clip of him on the Tonight show around 1968.

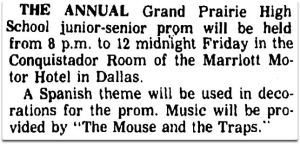

So anyway, Tiny was booked to do a little autograph party at the Melody Shop in NorthPark mall. I’m not sure what sort of crowd they thought they’d get, but it’s safe to say they did not expect 5,000 teenagers. The news report the next day was peppered with words like “pandemonium,” “swarm,” “mob scene,” and “human wall.” Who knew a 36-year-old man who strummed a ukulele and sang songs from the Victrola-age in a nasal falsetto would whip up that much enthusiasm amongst Texas teenagers?

My favorite description of the “riot” was this one:

Inside, a disheveled Tiny Tim was crouched on the floor behind a row of electric organs….. “Pretend he’s not in the store,” directed a manager. Tiny Tim, his shirttail out and his orange, green and brown tie twisted to the side, huddled alone on the floor. (“5,000 Kids Mob Tiny Tim,” Dallas Morning News, Jan. 24, 1969)

The story was even picked up by wire services. (Click article below to see a larger image.)

Amarillo Globe Times, Jan. 24, 1969

Tiny was back in Dallas a few months later, this time to do a book-signing at the downtown Sanger-Harris. (Yes! He wrote a book!)

No riot was reported this visit, but Sanger’s still packed by fans who wanted a book signed by Mr. Tim (who signed with a pink quill pen). While in town, he give a little interview and an impromptu performance at a press conference (am I the only person who sees shades of Jeffrey Tambor here?):

*

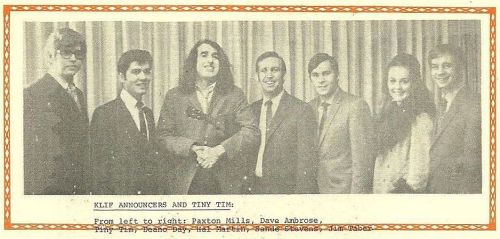

Also in 1969, he took time out to pose with KLIF on-air talent Paxton Mills, Dave Ambrose, Deano Day, Hal Martin, Sande Stevens (not sure if she worked for KLIF), and Jim Taber, seen below.

But wait, there’s more… he was back in Dallas in September, 1970 for a NINE-DAY engagement (two shows nightly) at Abe Weinstein’s famed downtown burlesque house. (I don’t know if the strippers took the time off while Tiny was in residence or if they might have entertained between his sets.) Here’s a clip from a press conference during that visit:

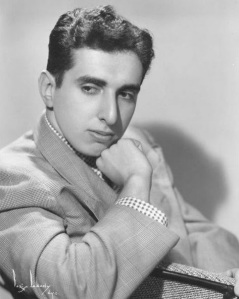

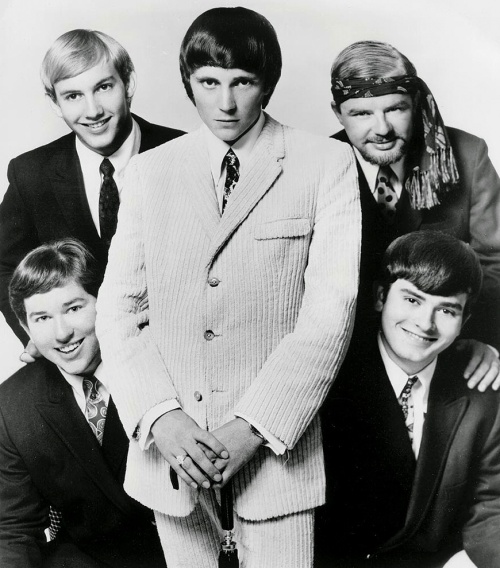

And, why not, here’s an early publicity photo of Herbert Khaury, the man who would one day become famous as the singer Bing Crosby once described as having (I paraphrase) a vibrato big enough to throw a Labrador through.

***

Sources & Notes

The 1969 Chanel 8 video is from the WFAA Newsfilm Collection held by the Hamon Arts Library, Southern Methodist University; it is posted on YouTube here (the first image and the three color photos of Tiny Tim are screenshots I captured from the video); the 1970 footage is from the same source and can be found on YouTube here.

KLIF promotional material found on eBay several months ago. The back of the card lists the KLIF’s top 40 of the week, here.

Glamour shot of Mr. Khaury found somewhere on the internet.

Tiny Tim Wikipedia entry is here.

One would be remiss in not mentioning Tiny Tim’s other ties to Dallas, namely his association with Bucks Burnett’s Edstock and Burnett’s tiny Tiny Tim museum from the 1990s. I’d link to articles in the Dallas Observer, but every time I go to the DO site my computer freezes. I encourage you to seek out these articles yourself.

More on Tiny’s January, 1969 visit to Dallas can be found in these Dallas Morning News articles:

- “5,000 Kids Mob Tiny Tim” by Jean Kelly, with photo (DMN, Jan. 24, 1969)

- “Magical Mystery Tour: On Meeting Tiny Tim” by Marge Pettyjohn, “YouthBeat” editor, with photo (DMN, Jan. 25, 1969)

*

Copyright © 2017 Paula Bosse. All Rights Reserved.

Merle and Lefty, in Corsicana

Merle and Lefty, in Corsicana

Younger… (via

Younger… (via Older…

Older…